Paintings of the Northern Renaissance, the result of Europe’s awakening from medieval stagnation, are different from works of the Italian Renaissance. This identity is the result of the creative path of individual masters, those who set the tone for all the fine art of that era. Van Eyck among such artists is usually mentioned in the first place, perhaps also because of the techniques of oil painting and composition of paints – his invention.

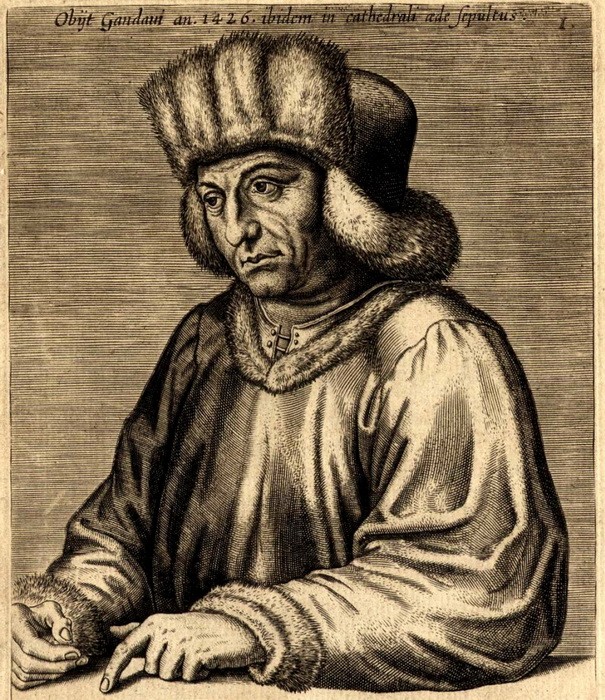

The Dutch Renaissance painter

Junior Van Eyck, in addition to painting – his main occupation, was interested in geography, geometry, chemistry, and thanks to his abilities were on a good score with the nobility. He entered the service of Count Johann of Bavaria, whose court was in The Hague, and later became the court of the Burgundian Duke Philip III the Good. In 1427, van Eyck was sent by the Duke to Portugal to paint a portrait of his future bride, Princess Isabella. The artist created two images, one sent to Philip by sea and the other by land, but to this day both portraits have not been preserved. Van Eyck himself returned to Flanders already with a wedding motorcade.

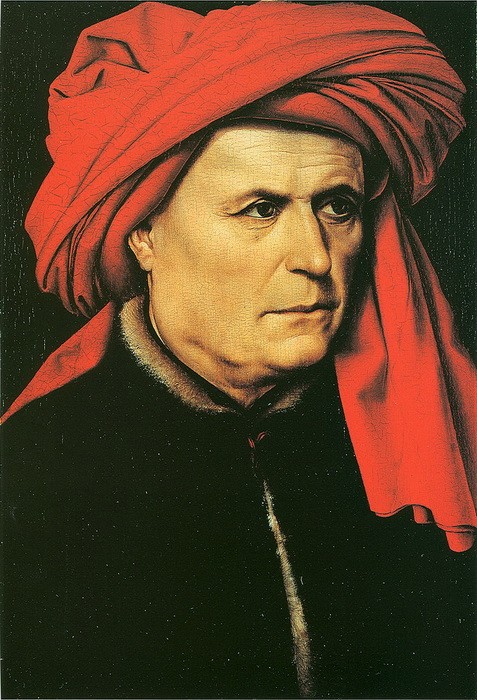

Rogier van der Weyden ‘Portrait of Philip the Good’

One of the most significant creations of van Eyck is considered to be the altar of St. Bavo’s Cathedral in Ghent, on the painting of which Brother Hubert began to work. In 1426, the eldest van Eyck died, and the altar was completed by the younger Yang. As noted by art historians, even if Van Eyck had not created during his career, except for the Ghent altar, he would remain one of the greatest representatives of the Early Renaissance. The 24 panels of the altar show 258 figures and the entire work demonstrate a new, Van Eyck style of painting that would later develop with other Dutch artists and become a hallmark of the Northern Renaissance.

Jan van Eyck ‘Ghent Altarpiece’, completed 1432, oil on wood

Departing from medieval traditions in the fine arts, Van Eyck, keeping most of his works on religious subjects, relied on realism. He paid great attention to details, which, on the one hand, gave the plot accuracy, objectivity, and on the other – often had a pronounced symbolic character. Van Eyck’s biblical characters and figures of saints turned out to be placed in a daily, “earthly” environment, where each element was depicted carefully and lovingly. In this sense, the influence of another Dutch artist, Robert Campen, now called the ancestor of the Northern Renaissance tradition, on the work of van Eyck is noted.

Kampen is considered to be the probable author of the paintings of the altar of Flemish and the altar of Merodet, made with much more realism than all the works of cathedral painting created by that time. Unfortunately, to establish the exact authorship of the artists of the Early Renaissance is difficult, because until the XV century custom to sign their paintings did not exist.

‘Portrait of a Man in a Red Turban’

Symbolism and riddles of van Eyck’s paintings

Here again, the innovator was Jan van Eyck – one of the first paintings signed by the artist is called “Portrait of Four Arnolphins”. This is probably the most recognizable work of the Dutch master – and this reputation is earned both by the amazing quality of writing, creating the effect of three-dimensional space, immersed in the interior on canvas, and ambiguous interpretation of what is happening in the picture, as well as the meaning of individual intriguing details.

Jan Van Eyck. ‘The Arnolfini Portrait’(or The Arnolfini Wedding, The Arnolfini Marriage, the Portrait of Giovanni Arnolfini and his Wife, or other titles) (1434)

Van Eyck is credited with the glory of the inventor of oil paints he improved the composition used by artists of the time. Paints based on oils have been made since the XII century, but these paints have long dried out, and once dry, quickly lost color, cracked. Van Eyck’s wide interests and his knowledge of chemistry helped the artist to improve the composition, making it possible to apply the paints in layers, both dense and transparent. Layered strokes made it possible to achieve voluminous images, a play of light and shadow – this was a feature of the Flemish style of writing.

The painting depicts the merchant Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini at the time of his marriage. The work to date has been controversial and the story is different in interpretation. There is no doubt, in any case, that this work by van Eyck is the first double portrait in the history of European painting. Interesting is the signature that the artist made. It is not placed at the bottom of the painting, but between the images of the chandelier and mirrors. The words “Jan van Eyck was here” are rather unexpected – it reminds not so much of the author’s signature as of the presence at some official event.

Other questions arise, for example, when looking at the figure of the bride – apparently not pregnant, despite the seeming signs, on the shoes thrown down, the reflection in the mirror behind the back of a man and a woman and several other symbols, the solution of which is interesting more than half a millennium since the creation of the picture.

Old stories and new paintings

Jan van Eyck ‘The Madonna in the Church’ (1438—

Much of Van Eyck’s heritage is dedicated to religious subjects, including a large number of images of the Virgin Mary. The Madonnas of van Eyck are placed in very realistic interiors, where every detail is painstakingly written. In this case, the author tends to violate the proportions – as in the painting “The Madonna in the Church”, where the figure of Mary seems unnaturally large in the interior of the temple.

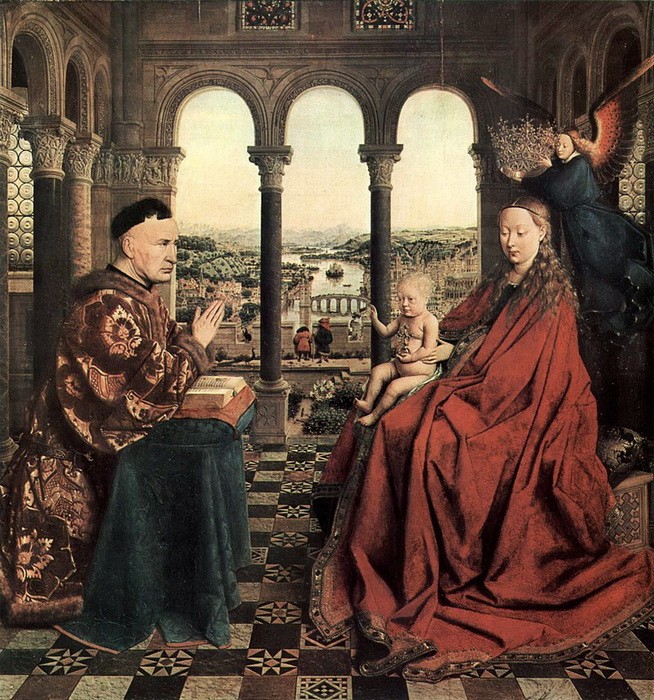

“The Madonna of Chancellor Roland” praised Counsellor Philippe the Good, Chancellor Burgundy, and Brabant. Most likely, the painting was ordered for the family chapel by the son of Roland. The canvas depicts three figures – the Virgin Mary, the Baby Jesus and the Chancellor himself. But the viewer’s attention cannot help but turn to the landscape, which is divided into three parts thanks to the window: behind the Chancellor’s figure one can see houses and city buildings, behind the Madonna – churches. These two parts are separated by a river, drawing the border between the secular and the spiritual. The riverbanks are symbolically connected by a bridge.

Jan Van Eyck ‘Madonna with the Child Reading’ (1433)

From 1431 the artist lived in Bruges, where he built a house and got married. The godfather of the first of ten children of van Eyck and his wife Margarita was Duke Philip the Good. The artist died in 1441.

Dutch art historian Karel van Munder spoke about the creative path of van Eyck:

“What neither the Greeks, nor the Romans, nor other peoples were not given, despite all their efforts, succeeded famous Jan van Eyck, who was born on the banks of the beautiful river Maas, which can now challenge the palm of the championship of the Arno, Po and the proud Tiber, as on its shores rose so bright that even Italy, the country of art, was struck by his brilliance.

Jan van Eyck. ‘Portrait of a Man in a Red Turban’ (Self–Portrait?), (1433)

The Northern Renaissance has its characteristics. Unlike the masters of the Italian Renaissance van Eyck and his followers followed the path of creating new art rather than reviving ancient traditions. In the paintings of the Dutchman in the appearance of man reads his personality, and the whole composition is harmonious and thoughtful, thanks to the unity of space. Van Eyck also discovered many techniques for painting, such as a three-quarter turn. And, undoubtedly, his work is a treasure trove of information about life, fashion, traditions of those times, a kind of Renaissance documentary.

Jan van Eyck ‘Portrait of Margaret van Eyck’ (or Margaret, the Artist’s Wife) (1439) oil on wood