“In times of rising nationalism, it is more important than ever to showcase the interconnectedness of cultures and demonstrate a shared cultural heritage,” said Max Hollein, director of the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, in a recent interview. With Met now closed because of the COVID-19 pandemic that is shaking the world, this message must become doubly relevant.

This year, April 13, marks the 150th anniversary of the founding of the Metropolitan Museum, but a series of anniversary celebrations and exhibitions, including a specially prepared historical tour “Making The Met. 1870-2020”, was forced to suspend. The museum has already announced about $100 million in losses that the institute will incur due to quarantine and a number of inevitable staff cuts. However, when it opens its doors again, its poster may be supplemented with exhibitions based on the latest world events.

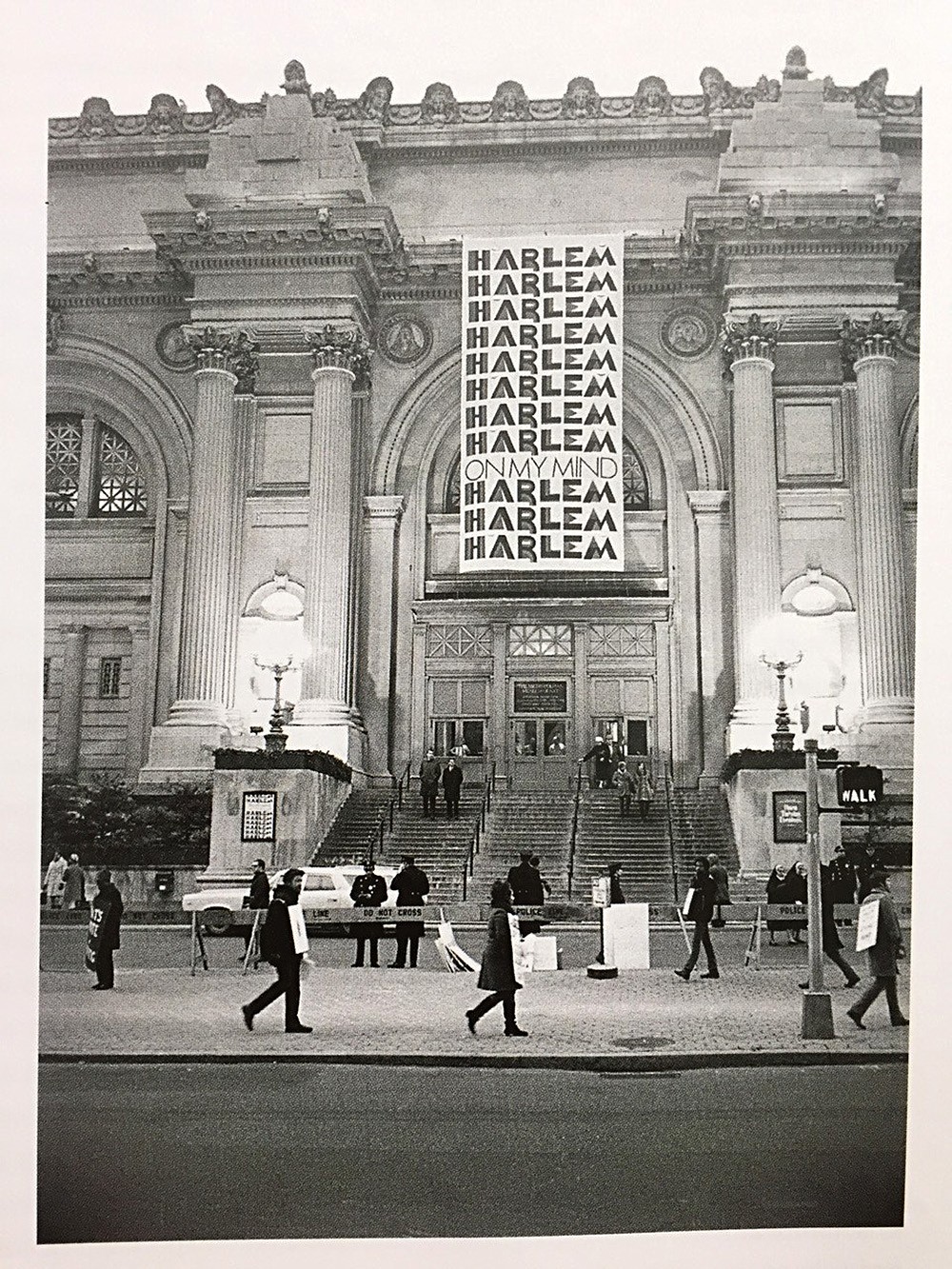

Protests in front of the Metropolitan Museum of Art during the exhibition “Harlem in Me”. 1969 Photo: Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.The Metropolitan was created in 1870 by a group of patrons and artists who believed that the city needed a museum that could compete with the Victoria and Albert Museum in London or the Louvre de Paris. However, the interests of art lovers then and for many decades remained lopsided. “‘They were primarily concerned with ancient history and the countries mentioned in the Bible,’ says Andrea Bayer, deputy director of storage and management. – They were also interested in the great Chinese civilization and European traditions. But the other huge parts of the world didn’t worry them too much. For example, the Mesoamerican works of art were long sent by the Metropolitan to the American Museum of Natural History and the Brooklyn Museum.

Working on mistakes

On the one hand, the Metropolitan tried to show art from all over the world more fully and actively; on the other hand, the museum, according to Bayer, “was increasingly confused about how to show contemporary art in its entire spectrum”. The status of postwar and contemporary art here was almost as ambiguous as that of archaeological finds from Met excavations in Egypt and the Middle East in the early 20th century or funeral and ceremonial sites of North American Indians. Let us recall that the Met did not always appreciate the art of the present – at one time the museum abandoned the collection of American contemporary art by Gertrude Whitney, which she offered him in 1929.

The exhibition “Making The Met” also reminds us of the notorious 1969 exhibition “Harlem in Me”, dedicated to the center of the cultural life of African Americans. The exhibition was ethnographic in nature, and there were no paintings or sculptures by an African-American artist – just photographs. According to Bayer, the museum “behaved inappropriately towards artists from Harlem, behaved inappropriately towards artists from New York; these were wrong steps, and almost certainly we still do them.

Native American art

By 1876, the Metropolitan Museum (founded in 1870) clearly defined the size of its potential audience. It included the population of the whole country, who needed to be given an art education and a sense of high taste. Thus, the object of the museum’s activity (exactly the object, since the audience, was attributed to a passive role) acquired a national scale. However, the task to educate the national consciousness of visitors has not yet been openly set by the founders.

By the end of the 1870s, the theme of aesthetic education of Americans dominated the reports of the Metropolitan Museum trustees. At the same time, it was supposed to use not national samples of fine art, but on the contrary, the import of foreign art objects was welcomed. It should be noted that aesthetic education was clearly practical in nature: the topic of development of the American industry, design, and art market was constantly raised. The trustees also announced the establishment of a system of medals or awards for American artists. This is an obvious claim to the museum’s participation in the formation of a national art school. In general, its state by the early 80s of the 19th century was assessed by the trustees of the museum is extremely negative: the artists lacked taste and knowledge, the design lacked originality, and it was directly detrimental to the national economy.

In the 80s of the XIX century trustees of the museum directed their efforts to determine the place of the museum in the life of the American nation. It was stated that the museum is an independent force in public education, which has a determining effect on production and commerce. Also in 1889, the report first mentioned the federal authorities: the president gave the museum paintings Velasquez and antique metal products. Thus, the collection at that time was not tied to objects of American origin, and the wealth of the museum’s collections was not assessed in terms of their American or non- American origin.

The year brought an exhibition of early American art (created in the colonies before the War of Independence), and the report does not refer to the exhibition itself, but to the fact that the exhibits were provided by leading representatives of the civil and church establishment.

This emphasis, in our opinion, is evidence that the museum became a space for the accumulation of social capital of the American elite of that time. In the 20th century, the museum underwent great changes. The new director of the museum, Caspar Clarke, whose appointment of trustees was called a joy for the American people, had previously held a similar position in the British South Kensington Museum. Nevertheless, the appointment of the foreigner was not perceived as damage to national pride. At the same time, a purposeful collection of samples of American art began, which was announced to be a particularly important aspect of the museum’s activity. There was, however, no talk of state participation in this process, and the main source of income was to be the patriotism and generosity of American citizens (to this end, each next report lists the missing works of American artists). This process seems to us to be particularly important. First, the body of work of the national art school, which reflected the highest expression of the creative forces of the nation, was to be formed with the participation of civil society, not the state. Second, it opened up a great opportunity to further assert the status of the American elite as patrons of American national art.

Since 1905, the main source for the work of the Metropolitan Museum has been its bulletin, and the trustees’ report contains only financial and economic issues. For example, the first issue of the bulletin revealed the essence of scholarship support for American artists. This scholarship guaranteed 34 months of stay in Italy and an exhibition of the results of work in the museum. According to its founders, the upbringing of an American artist was not to take place in his native country, but in a region strongly associated with classical art of antiquity and the Renaissance. Apparently, the American school of art had to fall to the roots of European culture to become one with it.

The motives for appointing a new Englishman director were also explained. This happened because Kaspar Clarke is a man of the people who made himself a democrat with an open mind, that is, in fact, an American. Thus, even if the stereotypes about the American national character that existed in the society did not influence making important personnel decisions in reality, they were used for their legitimization in the eyes of a wide range of citizens. It means that museums cannot be considered as some demiurges forming national identity from scratch, but are at the mercy of constructions created outside them. In addition, the first issue of the bulletin contains an announcement of lectures on the history of music in Italian, which will be read in the schools of “little Italy”, an unprestigious poor area of New York. This fact is at odds with the popular notion in the historiography of the authoritarian and anglo-conformist nature of American culture.

In 1906, was allocated a special fund of 1 million dollars for the purchase of paintings by artists-citizens of the U.S., with the theme of paintings were not specified. Consequently, the very fact of the existence of the artist of American origin was considered more important than the presence of a national plot in his work.

One of the notes on the Boston Museum of Art states that the museum is part of the national education system, along with the school and library. Thus, the museum could claim to participate in the formation of national identity on an equal footing with these institutions, whose role in this process was given so much attention by Eric Hobsbawm, one of the classics of nationalism studies.

By the end of the first decade of the XX century, the situation in the display of American art in the catalogs of the museum has changed. American art was no longer mentioned separately and was listed in alphabetical order, along with the works of European masters. Perhaps this means that a kind of protectionism within the museum space has ended, and museum workers decided that the works of American masters are on a par with the works from the Old World. The achievement of maturity by American art is also mentioned in an outside author’s guide to the museum from David Prior: “The Days of Custody of American Art are over”.

History

The Metropolitan Art Museum was first opened in February 1872 and was located in New York City, on Fifth Avenue, in house number 681. John Taylor Johnson, a railway worker, was a collector and it was his acquisitions that formed the basis of the museum. He also became its first president, under his leadership the Metropolitan, where there was only a sarcophagus of Roman catacombs and 174 paintings, mostly European, quickly grew. In 18773, after purchasing the Cypriot antiques, the Metropolitan moved off Fifth Avenue and moved to West Fourteenth Street. But this housewarming was also temporary, and after New York bought a museum, the Metropolitan moved again, this time definitively, to the eastern part of Central Park. It is located in the mausoleum of red brick, designed by architects Calvert Vox and Jacob Urey Mould. In 1926, Richard Morris Huds completed the facade of the mausoleum, and by 2006 the Metro was already about a mile long and was more than twenty times larger than the original building, built-in 1880.

The main Metro library is the Thomas J. Watson Library, named after its benefactor. Originally, the Watson Library collected books on art history, exhibition catalogs, and publications on auction sales to reflect the museum’s replenishment process. Some sections of the museum have their own libraries that relate to their specialization. The Watson Library also has antique books, which are art objects in themselves, including books with illustrations by Dürer and Athanasius Kircher and a copy of Le Description de l’Egypte, considered one of the best works of French printing, seized from Napoleon Bonaparte in 1803.

The medieval collection is located in the main building of the Metro in the gallery on the first floor; it includes six thousand individual objects. Many specimens of European culture are represented here, but still, most masterpieces from Europe are in Cloisters. The main galleries exhibit evidence of the gradual development of art since the Byzantine period, with a large number of cult objects, and in the side galleries – small items made of precious metals and ivory. The main gallery exhibits a richly decorated Christmas tree.

Cloisters were John D.’s first project. Rockefeller Jr., who was the main benefactor of the Metro. Founded in 1938, this gallery is a separate building, entirely dedicated to medieval art.

About 12 thousand exhibits from the end of the seventeenth to the beginning of the twentieth century are presented in the section of American decorative art. The section has 25 rooms, each of which is made in the spirit of a particular era or designer. There are a lot of products by Paul Rivera and Tiffany & Co.

Art Curators

The word “mentoring” comes from Latin curare, which means “to take care of someone or something”. That is why in Ancient Rome, curators were called people who served public baths, and in the Middle Ages – priests who saved lost souls. Only in the 20th century, this term began to apply to the organizers of museum exhibitions, but it took time for them to turn into one of the key figures of the art industry.

In the 1960s, the so-called ‘curatorial coup’ took place: works of art were no longer perceived as autonomous objects, and the context in which they were placed became very important. As the critic and writer, Bruce Altshuler said, “curators became creators on an equal footing with artists,” and this changed the attitude towards their cause and the exhibitions themselves forever. If you dream of trying yourself in this field, listen to the advice of professionals.

The development of contemporary art is influenced not only by innovative artists and their works. Often, new ideas and currents appear thanks to exhibitions and museum experiments, behind the organization of which are universal professionals: art curators.

Kelly Baum was appointed Curator of the Post-War and Contemporary Art Department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2017. She has spent the last five years curating the Contemporary Art Department at Princeton University Art Museum. She will work on the development of the collection and the planning of exhibitions at both the main Met building and the branch opening next year at the former Whitney Museum. During her work at Princeton University Art Museum, Baum has added more than 100 exhibits to her permanent collection, held many exhibitions, and organized an international program of art residences. Prior to that, Baum held curatorial positions at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum of Art at the University of Texas at Austin.

Kelly Baum was appointed Curator of the Post-War and Contemporary Art Department at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2017. She has spent the last five years curating the Contemporary Art Department at Princeton University Art Museum. She will work on the development of the collection and the planning of exhibitions at both the main Met building and the branch opening next year at the former Whitney Museum. During her work at Princeton University Art Museum, Baum has added more than 100 exhibits to her permanent collection, held many exhibitions, and organized an international program of art residences. Prior to that, Baum held curatorial positions at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Museum of Art at the University of Texas at Austin.

The new department of contemporary and contemporary art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York will be headed by Sheena Wagstaff in 2012. This appointment is due to the Metropolitan’s plans to move its collection of contemporary art to the Whitney Museum on Madison Avenue after the Whitney moves to Manhattan. Wagstaff has been the chief curator of the Tate Modern Gallery since 2001, and prior to that, she managed exhibition activities in the Tate Britain. Wagstaff has also worked at the Whitechapel Gallery, the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford and the Freak Art Center in Pittsburgh, where she was director of the collection, exhibitions and educational programs. According to The New York Times, this appointment demonstrates that the Met Museum is becoming a serious player in the field of contemporary art. Metropolitan Director Thomas Campbell said, “Tire has curatorial, scientific and administrative experience. And we need someone who can reach authoritative communities and is well known to colleagues here and abroad”.

Museum Collection

The museum was based on three private collections – 174 works of European painting, including works by Hans, Van Dyck, Tiepolo, and Poussin.

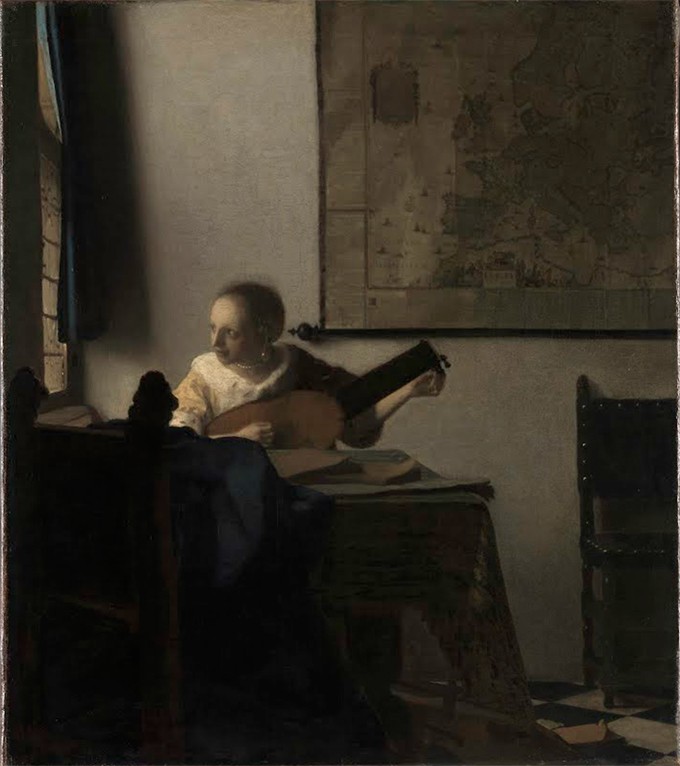

The collection grew rapidly, after the death of John Kensett 38 paintings from his private collection were transferred to the museum. But only in the XX century, the museum became world-famous. In 1907, the museum acquired its first painting by Auguste Renoir. Today, the Metropolitan is rightly proud of its collection of Impressionists and Postimpressionists. In 1943, the museum received by Maitland F. Griggs’ will two panels of Liberale da Verona (including the famous “Chess players”) on the plot of a love story from an unidentified knightly novel. By 1979, the Metropolitan had in his collection five of the less than 40 paintings belonging to the Vermeer brush. The collection of Egyptian art is considered one of the most complete and representative in the world.

Today there are more than two million works of art in the permanent collection. There are quite a few collections of different types in the Metropolitan area. The collection of engravings is extremely large. Some famous engravings can be found here in several copies and in different variants (for example, “The Game of Chinese Chess” (1741-1763) – an etching by a British engraver John Ingram based on a drawing by a French artist Francois Boucher, who depicts the Chinese national game of Xiangqi (Whale 象棋, Pinyin xiàngqí)). Among the major collections of photographs, for example, works by Walker Evans, Diana Arbus, Alfred Stiglitz and others.

In April 2013, collector Leonard Lauder donated to the museum his collection of 78 cubist works, including 33 works by Picasso.

Each year the museum publishes an “Annual Report”, which lists new acquisitions. The museum also publishes The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin.

In February 2017, the museum made publicly available 375,000 digitized images of art works from its collection. These paintings and photographs are free to use for both personal and commercial purposes (Creative Commons ‘CC0’ license level). In addition, they can be edited and used as part of new works.