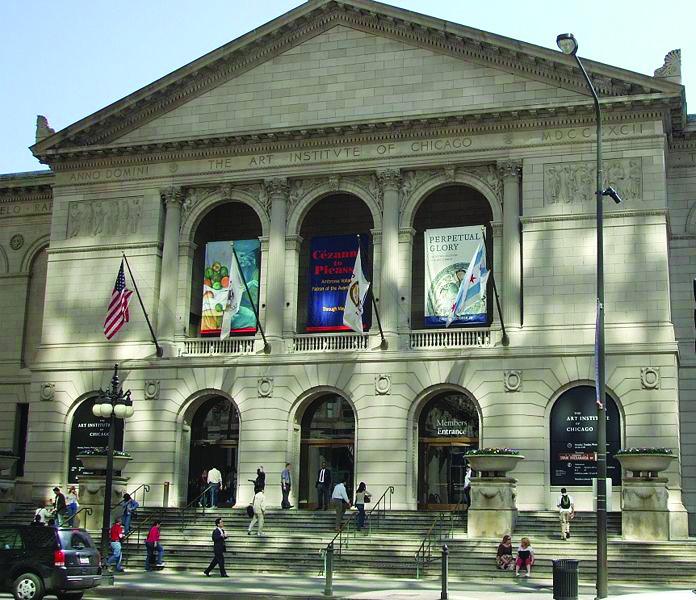

The Art Institute Of Chicago is the owner of one of the largest art collections in the United States. It is based on donations from collectors of the city and other individuals. The most significant gifts came from M. Ryerson, Berta Honoré Palmer, Annie Swan Corbun, Frederick Clay Bartlett, and Helen Burch Bartlett. The museum building, built in 1893, is located on Michigan Avenue.

The collection of the Art Institute is rich mainly in paintings. Interesting is a small collection of works by Dutch artists of the XVII century, which includes paintings by Rembrandt, Jacob Van Reisdal, Frans Hals, Jan Wall. Paintings by 19th century French painters – Jean François Mille, Camille Corot, Charles Dobigny, Eugène Delacroix, Narcis-Virgil Diaz de la Peigny, and Theodore Rousseau – are widely represented. The museum was world-famous for its beautiful collection of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings. Here you can admire such masterpieces as Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Breakfast of the Rowers and On the Terrace, Paul Cézanne’s Swimsuits, and Madame Cézanne in the Yellow Chair, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s The Moulin Rouge, Georges Sera’s Sunday Walk on the Isle of Grande Jacques, and Paris Street. Rain” by Gustave Caibott, “Self-Portrait” and “Arles Bedroom” by Vincent van Gogh. The gem of the collection is a collection of more than 30 works by Claude Monet, including several versions of “Water Lilies” and six canvases of the series “Haystack”.

The museum displays a large collection of American paintings, covering the works of leading painters of the continent: Frederick Remington, George Inness, Winslow Homer, John Singer Sargent, Mary Casset, Georgia O’Keefe, Grant Wood, Edward Hopper.

Claude Monet

The life and work of Claude Monet were often associated with an unaccountable desire for the impossible. He set himself an unattainable goal, by his own admission: to learn to depict the chosen object – be it a cathedral, a cliff, or a wheat haystack in front of which he erected his easel – in unique and changeable weather conditions, with different lighting. The artist somehow confessed to the Englishman’s guest: “The main goal is to convey his impressions, and then all the transient effects”.

In 1889, a critic contemptuously stated that there was nothing in Monet’s painting but “geographical place and time of year”. Only he missed the main thing. As objects soon change color and change their appearance depending on the season, weather conditions, and time of day, Monet hoped to capture their visual trail in these brief, unique, changing moments. Not only did he focus on the objects, but he also attached crucial importance to the atmosphere around them, the ever-changing, elusive light, and colors that he called envelope (meaning “environment”). “Everything changes, even the stone,” he wrote to Alice while working on the cycle dedicated to the facade of the Cathedral of Rwanda. But it is not an easy task to show the appearance of objects by displaying a moment of ghostly play of light and air. “I am chasing a dream,” he confessed in 1895. – And I wish the impossible.”.

All of Monet’s works are attempt to capture the fleeting effects of color and lighting. Standing with an easel in front of the Cathedral of Rwanda, or a wheat haystack on a frosty meadow near Giverny, or on the blown cliffs of the Norman coast, he will depict changes in lighting and weather throughout the day, and then the seasons. To recreate the desired effect, following your own feelings, you had to work in the open air, often – not in comfort. In 1889, a journalist described how a one-on-one artist with raging waves, at the foot of the coastal rocks in Etretat, “in a soaked cloak, writes a squall and salt spray,” trying to transfer the changing light to two or three canvases, which are loaded alternately on the easel.

An American newspaper with a clear skepticism told that on a single day in May 1908, Monet allegedly ruined the paintings for a hundred thousand dollars, and asked a question (unambiguous): Is he an artist or is he crazy? He began to refuse lunch – a bad sign for such a gourmet – and did not leave the bedroom all day long. He was suffering from headaches, dizziness, dark eyes. His relatives, as always, were close and comforted. Mirbo gently chewed him for canceling the exhibition, noticing that such behavior seemed “reckless and unhealthy” for “undoubtedly the best and most powerful painter of his time”. The praise cheered Monet up and he returned to the easel. “These landscapes with views of the pond and the reflections persistently haunt me,” he wrote to Jefferis in the summer of 1908.

In 1909, two years later than expected, Monet exhibited all forty-eight canvases with water lilies. By this time, the painful struggles of the artist were already widely known. The author of the material in Galois noted that the works were only shown to the public after the artist had long “doubted, worried and modestly”, while another critic, Arsen Alexander, informed the readers that Monet was a victim of overwork and “neurasthenia”. Most often, neurasthenia was ascribed to women, Jews, weak men, homosexuals, and moral perverts. Many were astonished to learn that Monet, this strong and cheerful “Vernon peasant”, had a giant wooden sabot and a nervous breakdown.

Monet’s emotional exhaustion should not have been blamed only on the winds that blew away his canvases, or on the rains that poured and nailed plants in his wonderful garden. And it was not only that he sat in the same place for a long time, day after day, looking closely at the same view – although experts agreed at the time that such an occupation, which requires almost complete immobility, can lead to neurasthenia, and in this case, it is possible to assume that in 1892 in Rouen, the artist was not accidental nightmares, in which the famous cathedral fell on his head. First of all, these “torments of creativity” were explained by the desire to create something completely new and original, truly revolutionary. He himself stated his task, as always, succinctly: “The main thing here is the mirror surface of the water, which is constantly changing, reflecting the sky”. The water on his canvases is really variable and becomes light green or dull purple, or orange-pink or fiery red. But the way in which Monet revealed the motif of water and the sky reveals a change in artistic vision – it is these bold experiments that, as Jeffroy argued, brought him to the brink of self-destruction.

Monet was the only one who wanted to show the fixed, mirror-like surface of the water close-up. Usually, a lot more painters were interested in a variety of “accompanying” effects: the flickering of moonlight on the ripples of the river, heavy waves hitting the shore. Monet himself was considered a recognized master of such landscapes: Edouard Manet once called him “Raphael of waters”. But at the lily pond, Monet was looking for more subtle nuances and tried to capture not only the plants on the water surface and their reflection but also the translucency and depth. He has already tried to transmit subtle metamorphoses that occur underwater. “I am concerned about everything that is impossible to transmit,” he complained to Jeffroix in 1890, when he wrote the species of Epta, “like water and algae, waves shaking in the depths. The pinnacle of this underwater quest was the canvas on which his stepdaughters Blanche and Suzanne sail in a boat “above the flowing transparency of the wonderful world of underwater flora with its ribbons of algae, dull and wild, oscillating and intertwined under the wrath of the current,” as poetically described this scene Mirbo.

Louis Gillée saw Monet’s water landscapes of 1909 with views of ponds in a different way. In his opinion, these compositions became innovative because of their abstractness. Indeed, he said, “pure abstraction in art is unlikely to take us further”. Monet could argue that his art is not an abstraction in comparison with nature, but rather an attempt to reflect it as accurately as possible – yes, almost an obsession with visual authenticity that conveys an ephemeral beginning. Jean-Pierre Oschede later stated that Monet did not create “abstractions”. And yet critics, like Gilles and some avant-garde artists, saw something different in these quests. In their eyes, the magnificent technique of Monet – shimmering strokes and colorful harmonies – is an escape from the everyday narrative. So realism in the image of the pond was much less significant than the formal means by which it was achieved, or emotions that awakened in the viewer by this hypnotic color rhythm. Let some critics write Monet off and call his art obsolete – but Gilles’s thesis of “pure abstraction” put him at the forefront of contemporary art in 1909.