The Ghanaian-born writer, critic, and theorist of modern art and contemporary music, Kodwo Eshun, who lives in London, wrote his article on Afrofuturism in the early noughties, and since then it has come to resemble Afrofuturism itself: some have heard of it, but few have read it, and some, looking at the new comic books with black characters or watching the recent blockbuster Black Panther, had no idea they were dealing with one of the most striking expressions of the aesthetic and philosophy of contemporary African culture.

Imagine a group of African archaeologists of the future (carbon-based life forms, silicon-based life forms, for some water is essential, for others not). They are excavating a certain African museum; scraps of documents and leaking hard drives allow them to date it to the time of our present, that is, the beginning of the twenty-first century. As they patiently sift through the debris, our United States of Africa (USAF) archaeologists will be struck by how often black diaspora subjectivity in the twentieth century was asserted through a project of cultural Reconquista. In their era of total memory, memories do not disappear. The art of forgetting disappears. Imagine them trying to reconstruct from found fragments the conceptual framework of our era, its basic parameters, and reference points. What will they see?

The War of CounterMemory

In our time,” U.S.-F archaeologists would decide, “imperial racism has taken away the right of black citizens to participate in the project of enlightenment. The latter therefore needed to prove their presence in the historical process at all costs. The corresponding need has rigidly defined Black Atlantic intellectual culture for centuries to come.

To establish the historical specificity of Black culture and to secure for Africa and its people the place in history denied it by Hegel and his followers, an archive of counter-evidence and counter-evidence refuting the colonial picture of the world had to be assembled and to turn the collective trauma of slavery into one of the cornerstones of modernity.

Inherent Injury

In an interview with the critic Paul Gilroy published in the anthology Small Matters, the writer Toni Morrison argued that the Africans who experienced captivity, kidnapping, mutilation and slavery were precisely the first truly modern people. They experienced existential loneliness as well as alienation, unsettlement and dehumanization, all of which philosophers like Nietzsche would later declare to be the essence of modernity. The forced displacement and commodification of people during the so-called Middle Passage of the slave ships – the passage from the shores of Africa to the shores of America – did nothing to plant civilization. On the contrary, they compromised the New Age forever.

The debate about compensation, which continues to this day, proves that these traumas continue to affect the modern picture of the world. No one is suggesting that we immediately forget all that we have tried for so long to remember. Rather, it is a question of maintaining the vigilance it took to bring New Age imperialism to justice in the future.

Tired of Futurism

The practice of counter-memory is defined as an ethical obligation to the past, to the dead, and the forgotten. This is why the creation of a conceptual toolkit for making sense of and bringing together different counter-versions of the future was at first perceived as unethical neglect of duty. Any attempt at futurological analysis was regarded with suspicion, wariness, and even hostility. Such sentiments prevailed in the scientific community throughout the 1980s.

African artists had their own good reasons to be disillusioned with futurism. The overthrow of President Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana in 1966 marked the failure of the first attempt to create the USF. Mass discontent and colonialist revenge made African socialist utopias extremely hostile. Until the end of the twentieth century, African intellectuals adhered in varying degrees to what Homi Baba in 1992 described as “melancholy protest. Tired of the future, the cultural figures of the “Black Atlantic” have also been withdrawn, little by little, from participating in the creation of the future.

Imagine archaeologists running emulators and trying to make sense of fragile files. They all agree that the future is the domain of chronopolitics, that is, territory no less tricky and dangerous than the past. They painstakingly sift through the archives of the twenty-first century and find themselves struck by what a discovery it has been for their ancestors, whose names have already been forgotten. They are deeply moved by the seriousness of the forefathers of Afrofuturism, by their sense of responsibility for what is yet to come.

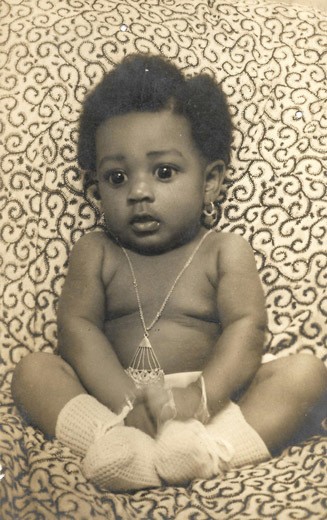

Felicia Abban. And the series “In Ghana. A Changing Portrait of Accra.” 1940-е. Black and white photograph. Courtesy ANO. Source: The New York Times

Now let us move into the early twenty-first century, a period in which dissatisfaction with the present is habitually masked by digital fantasies of a “beautiful far away.” Under such circumstances, the desire to look closely at the production of the future turns from a whim to an urgent necessity. Afrofuturism does not deny the tradition of counter-memory. Rather, the challenge is to extend it by reorienting it in time and inviting an intercultural black Atlantism to look not only to the past but also to the future.

Today it is clear that power is exercised not only through control of the past, but also through the ability to anticipate the future. Capital, as it did throughout the previous century, continues to pretend that the imperial archive simply does not exist. But now, power has also learned to govern by means of convincing pictures of the future by creating them, skilfully operating them, and communicating them to the addressee.

In the colonial era, in the first half of the twentieth century, the avant-gardists, from Walter Benjamin to Frantz Fanon, rebelled against the existing order, which relied on the control and representation of the imperial archive in the name of the future. Today the opposite is true. The powerful turn to the futurists and draw their power from the predicted versions of the future; they sentence the powerless to an existence in the past; the present is stretched: for some it immediately slips away into the past, for others it is directed toward tomorrow.

Science Fiction Capital

The modern strategy of power was characterized in 2000 by the cultural scientist Mark Fisher as “science-fiction-capitalism”, that is, the synergy, the fruitful interaction of capital with future-oriented media. The alliance of cyber-futurism and neo-economic theories suggests that information itself is an economic resource. Accordingly, information about the future becomes a strategically important commodity. It comes in different formats – it can be mathematically calculated (computer simulations, economic forecasts, weather reports, futures transactions, analytical and consulting reports), or it can be freely presented (science fiction films and novels, musical compositions, religious prophecies, venture capital). There are also a hybrid, borderline forms – for example, global scenarios developed by professional market consultants-futurologists.

Judging by the number of new media generated by the computer boom of the 1990s, it is obvious that the entire industry of the future, i.e. the combination of technoscience, artistic means of expression, forecasts of technological development and the products of futurologist marketers, worked for the push towards a technological boom. In this context, it would be naïve to continue to regard science fiction (which is undoubtedly part of the industry of the future in its broadest sense) as merely an attempt to predict a distant future or a utopian project designed to visualize alternative forms of society.

Rather, we can agree with Samuel Delaney, who in The Last Angel of History calls science fiction “a substantial distortion of the present. More precisely, science fiction is not about predictions or utopias: rather, to use William Gibson’s words, it is a way of programming the present (cited in: Eshun 1998). The entire history of the genre shows that science fiction has had little interest in the future at all; it has tried to format the present so that a preferred scenario becomes reality.

Hollywood’s popular technological fantasies, from The Truman Show to The Matrix, from Men in Black to Dissenting Opinion, can then be seen as hidden advertisements for computer technology, helping to create a reality where, in turn, the glorified technology will begin to work for real. As the new economy spreads, the virtual worlds of the future begin to produce more and more capital. The functions of convincingly painted pictures of the future oscillate between prediction and control: they draw us into themselves, demanding that we embody them.

The Industry of Future Worlds

Today, science fiction is the advance development department of a giant factory of future worlds, which seeks not only to successfully predict tomorrow, but also to control it completely. Big corporations want to control the unknown by making decisions based on proposed scenarios, and civil society responds to future upheavals by assimilating the manner of action described in science fiction. The power of science fiction is the power of falsification; it seeks to rewrite reality without regard to plausibility, whereas scenarios rely on controlling and predicting possible alternatives.

Both science fiction films and screenplays are examples of cyberfuturism, telling of events that have not yet happened, in the past tense. In this sense, futurism has nothing to do with the Italian movement of the same name, nor with the Russian avant-garde. Rather, it is an attempt to model in the long term possible developments in the interval from foresight to predestination.

Imagine members of a Pan-African archaeological expedition combing the excavation area with their chronometers, sifting through the dust and ash, reading the instruments; judging by the readings of the hands, the concentration of hostile predictions is dangerously high. The frequency of the dystopian predictions is so high that their realization could threaten the lives of archaeologists themselves. But the scientists are calm: the off-scale gauges testify above all to the feverish heat of suppressed desires in the host markets.

Market Anti-utopia

The main goal of global scenarios is to secure markets in the future; Afrofuturism has a different goal: it is important to prove that, whatever the future predictions, Africa will grow in importance. The situation on the continent itself is substantially predetermined by frightening global forecasts, coming economic cataclysms, predictions of meteorologists, data on the spread of AIDS and on average life expectancy. All sources in unison threaten poverty for decades to come.

The credible pictures of the future, commissioned by multinational corporations and NGOs, leave us helpless: we can only weep and wail in helplessness. These versions of supposed development are the flip side of the corporate utopias that secure the future of industry. Only here we are not lured with wide smiles all over the screen, but, on the contrary, we are frightened by the prospects of exploitation and unfavorable forecasts for many years to come.

In an economy powered by NF capital and marketing futurism, Africa always remains a zone of total anti-utopia. Market forecasts predicting a socio-economic crisis in Africa always find an audience. Market-based dystopias seek to warn against exploitative scenarios, yet their discourse ascribes near-total infallibility to predictions.

Addressing museums

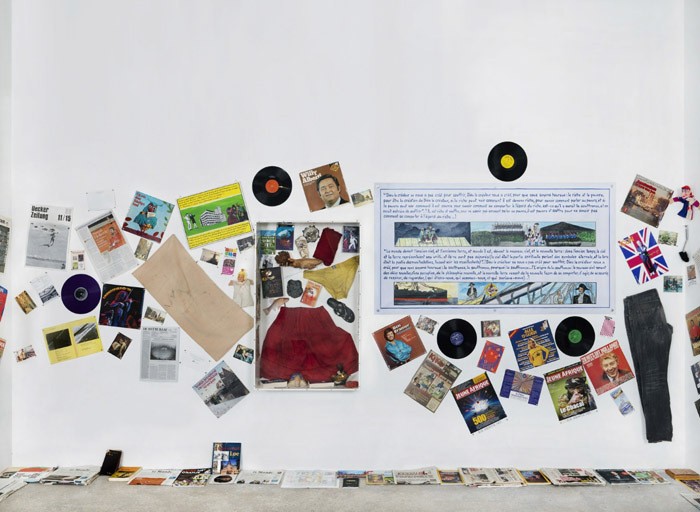

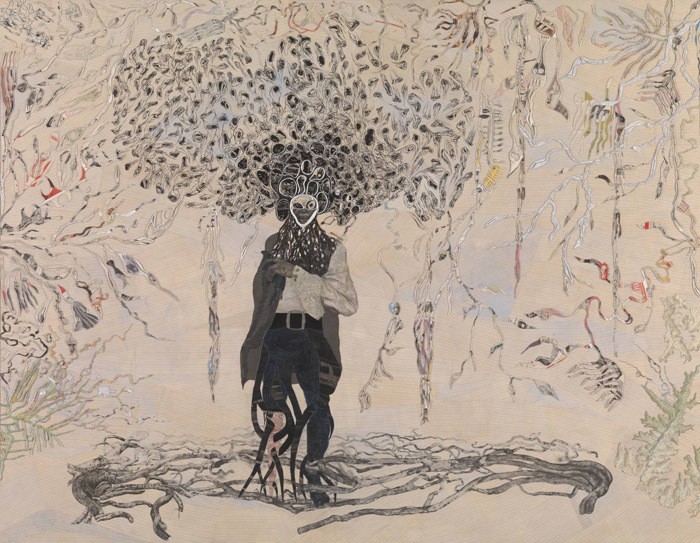

For contemporary African artists, it is fundamentally important to make sense of the production and dissemination of such ideas and to intervene in chronopolitics. Possible variants of chronopolitical actions are presented in the work of authors such as Georges Adeagbo and Meshak Gaba. Both artists decided, in the tradition of Marcel Broodthaers and Fred Wilson, to imitate museums by exposing, deconstructing, ridiculing, and critically affirming an institutional system of knowledge tied to a strictly defined socio-cultural and historical context.

Gaba’s “Museum of Modern Art” has become “both a critique of the museum as an institution as it is understood in developed countries and a utopian construction, a possible model of a non-existent institution. The dual optics – simultaneously critical and utopian – are related to the figure of the artist himself … who discovers structure where there is none, not forgetting the limitations of existing models relating to a particular social and economic order that is based on colonial domination in its most brutal manifestations” (Gaba 2002).

Advance Measures

The Afrofuturist art project can draw on this “dual optics” combining “critical and utopian” origins to show how a purely negative prognosis for Africa emerges in general and how it becomes generally accepted, as well as to rethink this approach to the future. In 2005 the African artist showed that there is a strictly defined conceptual implication in these ruthlessly catastrophic social projections.

Delving deeper into this dimension, the African artist will find that there is room for a variety of anticipatory maneuvers, imitations, manipulations, even parasitism. The request for a bright corporate future, illustrated by full-screen smiley-face advertisements, can be taken as a very wicked joke, mocking transnational delusions. The exploitative interpretation that Africa will inevitably face hopeless despair for the next 50 years can be deconstructed and dismantled by the artist.

Three different but overlapping spheres are implied here: working in the world of mathematical modeling, working in the world of fiction, and – as Gilroy described in Between the Camps (2001) – articulating the future embedded in the spoken language of the black population. We have already talked a little about the possibilities that the first two areas offer for African art; now we turn to the third. Working with this material requires a serious and patient parsing of sonic representations of extraterrestrial space and of the future, as well as an analysis of scientific and technical fiction.

Imagine an archaeological expedition in its spare time. Scientists sit around their liquid gel screens while processors calculate possible futures for real cities through the Global Scenarios app, an advanced video game that compiles all possible developments. Lagos has been chosen as the scene so far, with other cities to come in the next rounds. Players are prompted to specify parameters for the development of the transport system, energy consumption, waste management, location of residential, industrial and commercial zones. Based on these data, the system will produce a picture of the world of the year 2240.

Sound Scenarios of the Black Atlantic

Afrofuturism is unimaginable without the diversity of its sonic processes, whether conversational, intellectual, or syncopated, without all of its sonic hypostasis. The reality of the everyday existence of the spoken language of the black population can be devastating for the usual methods of contemporary art. However, the stories of the past of the future can also serve as an important source of inspiration.

Imagine that artist Georges Adeagbo came up with an installation based on the album covers of Parliament-Funkadelic 1974-1980 and constructed a new cycle of political-socio-racial-sexual fantasies from the cultural memory of his era. Imagine that archaeologists of the future have unearthed fragments of his work: the techno-occasions of tomorrow’s yesterday.

Afrofuturism listened carefully to the calls of black artists, musicians, theorists and writers in those years when they found it difficult to imagine for themselves any future. In 1962 the composer and jazz orchestra leader Duke Ellington published a short essay entitled “The Space Race” (Ellington 1993), where he tried to make the future serve the black liberation movement. However, as early as 1966, Martin Luther King argued in “In Which Direction Are We Going?” that the gap between societal development and technological advancement was so great as to call into question the whole idea of socio-economic progress (Gilroy 2001).

Afrophilia in the highest

Between the late 1960s, when the Black Power movement waned, and the mid-1970s, when Pan-Africanism and Bob Marley began to gain in popularity, Afrodiaspora musical culture was characterized by an Afrophilia that combined idyllic visions of the anarchic order of liberated Africa with the idea of a high-tech African future. These two aspects were in a precarious but constructive balance.

In the mass consciousness, this balance was embodied by Egyptian motifs in the work of Earth, Wind, and Fire. However, attempts to combine pre-industrial and high-tech Africa were made as early as the 1950s, during the lifetime of the composer and musician Sun Ra, who devoted his life entirely to the creation and affirmation of the original cosmogony.

The Cosmogenetic Moment

In 1995 the London-based Black Audio Film Collective released The Last Angel of History, (aka The Mothers’ Community), a documentary that is still considered the most detailed and detailed account of Afrofuturist ideas in their entirety. It has a central character, a time traveler named Information Kidnapper, who links the themes of music, space, futurology, and the diaspora. African musical compositions are presented here as a kind of communication system – the individual elements of the code to the secret black technology that should ensure the entire diaspora’s future. The storyline with the secret black technology allows Afrofuturism to reach a point of speculative acceleration.

Imagine archaeologists squinting into the cracked screen of a micro-video installation where you can discern the Information Snatcher trapped in the dungeons of West African history.

Director John Akomfrah (a member of Black Audio) and screenwriter Edward George drew on the ideas of the theorist John Corbett. It was to his article “Brothers from Another Planet” that the title of John Sayles’ 1983 sci-fi film refers: the main character, an alien, escapes from his intergalactic enslavers by pretending to be African American. Akomfrah and George are largely guided by the work of Sun Ra and his band The Arkestra, as well as one of the founding fathers of dub – musician, producer and songwriter Lee Perry – and Parliament-Funkadelic producer George Clinton. All three are important to our story as authors who have used recording studios, vinyl records, album covers and record labels to promote the mythological, programmatic and cosmological ideas embedded in their conceptual albums.

The work of The Arkestra, the production of Perry’s recording studio The Black Ark and the Parliament-Funkadelic album series The Mothership Connection (1974-1981) allowed Corbett to argue that all of these artists “worked largely independently of one another with a common set of mythological images and symbols, developing themes of space exploration and life on other planets, deriving their image system from there.

Unspecified identifier

By the early 1980s, sequencers, samplers, synthesizers, and other digital devices and computer programs had been invented, so it was impossible to attribute any particular identity to music, including racial identity. It was no longer possible to determine the racial identity of musicians the old-fashioned way: you just couldn’t tell anything by listening to samples.

So there were gaps in racial identification, it became unclear to the listener, and musicians had the possibility of heteronomy. The human-machine interface became both a condition and a subject of Afrofuturism. The fictional cyborgs of Detroit techno-musicians Juan Atkins and Derrick May allowed their creators to move away from a predetermined musical identity and assimilate within alienation. Thelma Golden, in her notes on twenty-first century post-black aesthetics, writes that the process of musical self-definition was more successful in studio sound recordings than in the visual art practices that developed in galleries.

The Consequences of Revisionism

Gilroy argues that the development of these trends coincides with the emergence of pockets of tension in the historical process. But if one were to view the visions of the future held by most blacks in this way, one would have to treat them as byproducts of more general social and liberation processes, rather than as an important element of them. Among the historical phenomena of this kind are black eschatology, the Black Power movement and other spiritual-political movements, as well as postwar political-esoteric sects: the Nation of Islam, Egyptologists, followers of Dogon cosmology and stolen heritage theory.

The eschatological conceptions of the Nation of Islam combined esoteric hypotheses about the origin of the human race (with an emphasis on racial minorities) with a doctrine of time that predicted eventual catastrophe. Hogomelli, a Dogon mystic, demonstrated to the French ethnographers Marcel Griaule and Germaine Dieterlin that he knew the characteristics of the star Sirius from the constellation of the Great Hound: it turned out that the Dogon cosmological myths contained strikingly accurate astronomical information. Egyptologists, inspired by utopian authoritarianism, sought to find evidence of Africa’s lost grandeur in the pre-industrial era. “Martin Bernal’s Black Athena (1988) and George James’s Stolen Heritage (1989) almost simultaneously announced to the world the conspiracy of whites to cover up the fact that all science had in fact been stolen from Africans. Henceforth, the Hegelian tradition was to be reconsidered, for the origins of civilization were not to be found in Europe, but on the black continent.

Kanfar with the heads of an African man and a Greek woman. About 480-470 B.C. Ceramics. Princeton University Museum of Art. Photo: Bruce M. White. Reproduced on the cover of several editions of Martin Bernal’s Black Athena

Afrofuturism was by no means a naive attempt at self-praise. The obscurantist Manicheism of the Nation of Islam, the attempts at retroactive compensation by Egyptologists, the Dogon cosmology, and the complete reversal of the Stolen Heritage picture of the world are, of course, conspicuous. But if one analyzes the political origins of these square futurologies, one can gradually discern a whole chain of competing views, each seeking to reshape history in its own way. In any attempt to understand the origins and distribution of belief systems, one is struck by the fact noted by Gilroy: “…even when the movement that gave rise to them subsides, there remain traces in the form of temporal perturbations.

By creating perturbations and deviations in time and anachronistic “pockets” that disrupt the linear movement of progress, these versions of the future correct the logic of development according to which blacks were exiled to prehistoric time. In a chronopolitical sense, these revisionist projects can be interpreted as a series of competing versions of the future, seeping in varying degrees into the present.

The revisionist approach is shared by self-taught historians like Sun Ra and the author of Stolen Heritage, George James, and by contemporary intellectuals like Toni Morrison, Greg Tate, and Paul D. Miller. The notion that Africans, who knew firsthand what captivity, kidnapping, mutilation, and slavery were the first truly modern people, is extremely important because it makes slavery a cornerstone of the New Age. The cognitive and conceptual shift that had to take place in society for such a statement to be possible in principle juxtaposes philosophy with inhumanity and cruelty with the progressive course of time. The challenge is to forcibly conflate different systems of knowledge by pointing out the engagement of any conceptual apparatus.

Afrofuturism can be interpreted as a development of the ideas embedded in Morrison’s revisionist tenets. In an interview with the writer Mark Sinker, the cultural scientist Greg Tate suggested that the distinction between signifier and signified can be understood as a Middle Passage, separating meaning (i.e. meaning) from signifier (i.e. letter). Juxtaposing racial discrimination with semiotics allows us to conflate historical trauma with structuralist tools. When these two lines intersect, anxiety becomes so strong that it distorts structuralism and transforms discrimination and trauma into abstraction.

The Benefits of Alienation

But Afrofuturism does not think to stop at fixing the history of the future. It is not just a matter of including as many black characters as possible in the science-fiction narrative. These methods are only the first tiny steps toward a more universal discovery, which Greg Tate articulates as follows: members of the African diaspora experience the very disconnection from society described in science fiction. Black life and science fiction are virtually one and the same.

In The Last Angel of History, Tate argued, “The very form, the conventional ways of narrative and the treatment of subjectivity force the focus on the hero, who comes into conflict with the power apparatus of society. At the deepest level, he experiences general cultural unsettlement, alienation, and detachment from society. Many science-fiction stories are built around the hero’s struggle with society pushing him out and the circumstances in which he has no place. In general, in the same categories can be described the experience of most black people in the post-slavery period of the twentieth century.

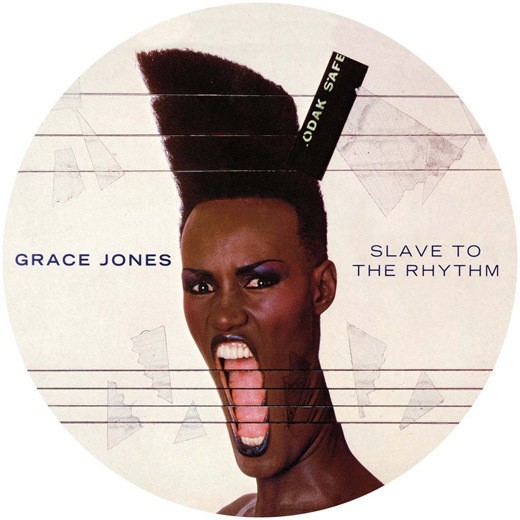

Grace Jones Slave to the Rhythm vinyl album cover, 1985

At the beginning of the last century, Du Bois introduced the concept of “double consciousness” to describe psychological and structural alienation. Generally speaking, alienation from a psychosocial point of view is inevitable. And artists belonging to the African diaspora have learned to use it to their advantage, setting a context that can lead to alienation. The main characteristic of Afrofuturism is that it assembles heterogeneous concepts and mediated counter-evocations, achieving triple or even quadruple awareness, degrees of alienation previously unattainable.

Imagine that late at night, when the excavation is already sealed and awaiting the continuation of the work in the morning, when all the expedition members have been safely decontaminated, one of the archaeologists sees six turning circles in his dream. As if the Invisible Man’s dream had come true, and he would hear Louis Armstrong’s What Did I Have to Do to Be So Black and Blue, but only six times brighter.

Addressing Alien Worlds

Afrofuturism uses other worlds as a hyperbole to reconsider the course of history, to examine the domestic consequences of abductions and forced relocations, and to understand how this affected the formation of Black Atlantic subjectivity: the transition from slave to Negro, then, successively, to colored, civilized, black, African and, finally, African American.

Assuming that all these transformations were forced rather than voluntary, the hypothesis of the involvement of other civilizations provides grounds for reasoning and a reassessment of values. Reflection on other planets ceases to be an escape from reality and takes advantage of the possibilities of images of space and space to make sense of the particularities of self-identification under the weight of constant racial animosity.

It would be a mistake to assume that blacks are just waiting for science fiction writers to visualize their world. On the contrary: science fiction, a genre marginal to the literary system but crucial to understanding the contemporary world, can provide the necessary allegorical tools to describe the holistic experiences that blacks have had in the postcolonial period of the twentieth century. Rather, science fiction is reformatted to fit into the historical conception of the African diaspora.

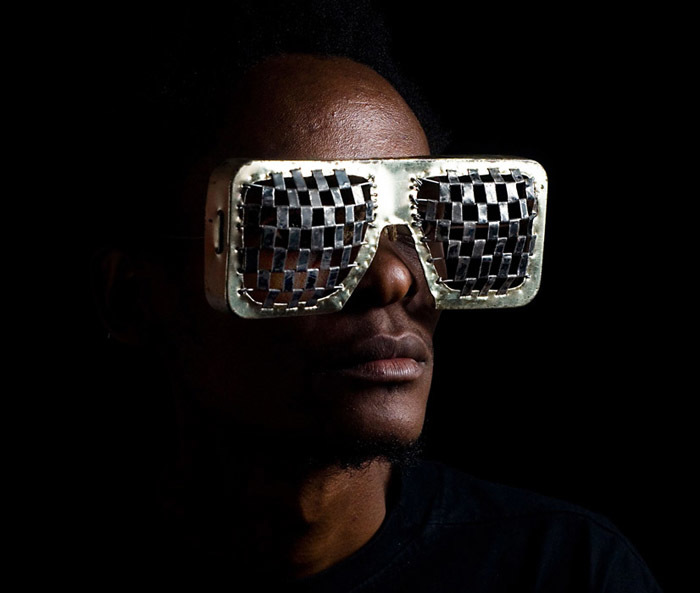

David Alabo. Panther. Digital collage. © David Alabo

In response, Afrofuturism provides a series of mystical returns to the systemic trauma of slavery, presented in the categories of science fiction. Here it would be appropriate to recall Mark Sinker’s article “To Love an Alien,” which cites a line from a Public Enemy composition entitled Welcome to the Terradome: “The apocalypse has happened. Sincker interprets it as follows: the people of Africa experienced the experience of slavery as a kind of apocalypse comparable to alien abduction: “The ships came a long time ago. They devastated entire communities, forcibly removed and genetically altered huge strata of the population… Africa, America, and hence Europe and Asia in many ways became continents inhabited by Aliens.

Time jump

Modern electronic music is seen by Afrofuturism as an intertext consisting of systematic quotations that can be used to artistically reshape chronology and introduce a necessary amount of fiction into history. Lyrical passages become the basis for historical conclusions. Social reality and science fiction are interconnected and echo each other, sometimes within a single phrase. During the Cold War era, encounters with aliens and alien abductions were perceived as a morass reminiscent of a nightmare already experienced in reality.

All the signs that supposedly indicated close contact with other civilizations had already been observed in earlier years, but at this time they took on a truly catastrophic scale. Collective hallucinations are superimposed on the experience of the Midway Transition. The task is not to question the historical reality of slavery. It is to be subjected to a time leap that directs the entire subsequent course of history in a different direction, explaining events through post-war social fiction, fiction and actual science fiction. All of this begins to seem like an elaborate plan to conceal and acknowledge trauma.

Black Atlantic Mythology

In 1997, the aesthetic of rupture and alienation was taken to its logical limit by the band Drexciya, a rather mysterious collective of producers, electronic artists and designers from Detroit. In the author’s commentaries for their 1997 album The Quest, the members of Drexciya offered an original reading of Midway in the vein of science fiction. According to their legend, the Drexians are the unborn children of “pregnant African slave girls, who were thrown overboard by the thousands during childbirth because the sick “goods” became a nuisance and were of no use to anyone.

Abdul Qadeem Haq. From the Drexciya comic book project. 2019. Source: www.indiegogo.com

Are humans capable of learning to breathe underwater? After all, the fetus in the womb is just fluid. If the mother gave birth in water, could it be that the babies did not need to learn to breathe air? The latest scientific experiments have shown that mice can breathe dissolved oxygen; moreover, a premature infant was saved from almost certain death by filling its underdeveloped lungs with oxygenated fluid. These absolutely authentic facts, combined with stories of water and swamp monsters in the coastal swamps of the southeastern United States, make the fictional Drexians surprisingly plausible.

Gilroy’s “Black Atlantic” (1993) was perceived by Drexciya ideologues as a science fiction essay, from which the theory of four stages of migration and mutation on the way from Africa to the Americas then emerged. From here whole mythology of the Black Atlantic is built up, which successfully makes sense of the entire evolution of black subjectivity. A whole series of paintings by contemporary African-American abstractionist artist Ellen Gallagher grew out of the Drexians’ ideas, and theorists Ruth Mayer and Ben Williams responded with critical articles.

Soon the Drexciya project spread into space as well. Before the release of the album Grava 4 in 2002, the band contacted the International Star Registry in Switzerland to get the right to choose a name for the star. Thus a star appeared, officially entered in the registry as Grava 4, and it, in its turn, gave a name to a new section of Drexciya’s musical creativity. The band’s ideologists spun their speculations on electronic compositions and tied them to a realistic point in space, thereby giving themselves quite an imperial right to hand out names and colonize intergalactic space.

Of course, buying the rights to own a distant star is absurd, but this does not negate the obligations of the contract. The process of its ratification turns into an unusual artistic action: we have before us a musical composition, where the metaphorical is combined with the legal, and electronic music with cartography. That is, the real clauses of the contract are combined with a musical composition and an astronomical atlas in order to colonize the space of the audiovisual imagination even before the armed landing.

It turns out that Afrofuturism can be thought of as a program for restoring and reclaiming the stories and counter-versions of the future created in an era hostile to Afrodiaspora and its further development. In addition, Afrofuturism is a space within which crucial work can be done to produce tools that can influence the political order of today. The creation, translation and modification of ideas and approaches in theoretical texts and imaginative writings, electronic music and sound, visual arts and architecture are only part of the extended sphere of Afrofuturism, which is treated as a multimedia project distributed over the nodes, centers, rings and stars of the Black Atlantic. This toolkit, developed by intellectuals from the ranks of Afrodiaspora for their own needs, and the imperative to encode, borrow, adopt, translate, erroneously reproduce, rework and revise relevant ideas under the conditions described in this article, is likely to be relevant for many decades to come.