Sadie Barnette has joined Jessica Silverman Gallery in San Francisco. Barnett’s work explores race, sex, and love. In 2015, the artist participated in the Studio Museum residency program in Harlem. Her work can be found in the permanent collections of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Perez Museum of Art in Miami, the Blanton Museum in Austin, and other institutions. The artist is also represented by the Charlie James Gallery in Los Angeles.

Jessica Silverman Gallery organizes interesting exhibitions, builds artists’ careers, and collaborates with collectors who are interested in positive origins. Its mission is to support artists whose attitude to contemporary culture is such that museums and other government agencies want to understand and accept their work.

Jessica Silverman founded her gallery in 2008. The artist got her Bachelor of Arts in Studio Art from Otis College in Los Angeles and her Master of Arts in Curatorial Practice from the California College of the Arts in San Francisco.

Her late grandfather Gilbert Silverman, who along with his wife Leela was America’s leading Fluxus collector, Jessica developed a nose for content and a desire for formal innovation very early on.

The gallery has participated in many qualifying art fairs. Last year, its annual calendar was featured at Art Basel Miami Beach, FIAC Paris, the New York ADAA Art Show, and San Francisco Fog Design + Art. Silverman sits on the Expo Chicago Selection Committee and is a member of the American Art Dealers Association.

Works by gallery artists have been purchased by museums around the world, including the Tate (London), Center Pompidou (Paris), Reina Sofia (Madrid), MoMA (New York), MCA Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago, and many others.

For nine years, Silverman served on the San Francisco Arts Commission. There she oversaw the acquisition and commissioning of art for facilities such as SFO Airport. Since then she has advised real estate developers such as Mark Company, Troon Pacific, and related companies.

SAN FRANCISCO – The Historical Archive is so often understood and formalized (and institutionalized) as a relic of some past. It is often space where memories and depictions of history compete for supremacy and dominance, and space where “official stories” – stories of hegemony – emerge. But throughout her work, and especially in two of her most recent projects, Sadie Barnett has demonstrated creating an archive in a local language that not only undermines the standard or traditional archival form but also points to the future.

Barnett was born and raised in Oakland. She describes the themes and aesthetics of her work as an abstraction in the service of everyday magic and American survival. Her work, to quote Essen Harden, is not just a love letter to her hometown, but a love letter to black possibilities, liberation, and rebirth. This is a motif apt for the cultural production of the Bay Area, as Oakland and San Francisco are constantly gutted by black life through violent, supplanting gentrification processes.

Sadie Barnett focuses on drawing, photography, and large-scale installations. Through the prism of art, she explores black life, personal stories, and politics through material research. She lives and works in Oakland, California.

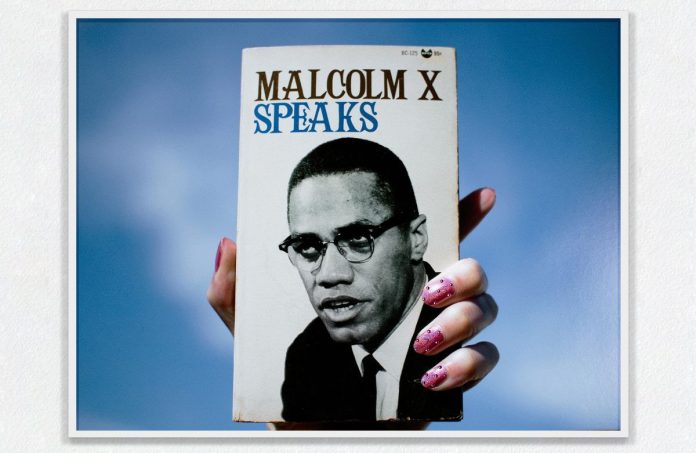

Sadie Barnett used her father’s 500-page FBI dossier file as source material for her work. The file has various family documents. It includes relatives’ names, birthdays, military awards, and interviews with her father’s employers, high school teachers, and his childhood neighbors.

Her father, Rodney Ellis Barnett, was a member of the Black Panther Party, which founded a branch in Compton, California in 1968.

After the branch was established, the FBI put Rodney Barnett on the COINTELPRO watch list. This FBI program conducted a complex network aimed at discrediting, dismantling, and destroying black radical activists, organizations, and movements. As a result of his daily movements and activities, he was constantly monitored. He was eventually fired from his job at the US Postal Service. Her father’s involvement with Black Panthers and the FBI files has and continues to influence her work.

In 2016, Sadie Barnett created an installation called Do Not Destroy, in which snippets from files were selected. This work made its debut at the Oakland Museum in California as part of the exhibition which was called All Power to the People: Black Panthers at the age of 50.

Her new project, The New Eagle Creek Saloon, is a recreation of the gay bar her father ran in San Francisco from 1990-1993. It was the first black-owned gay bar in San Francisco.

The installation was marked by her father’s dedication to people who speculated that making him a safe place for black homosexuals in the racially antagonistic San Francisco scene was an extension of his political work with the Black Panthers.

Barnett’s project is also a revival of her father’s bar from the erased annals of San Francisco queer history, tangible memory of the queer sociality of blacks that is rapidly being ousted from the ennobled city.

It was created in an attempt to understand the creation of space as an alternative archival form and to offer the same spatial opportunity for filiality and gatherings of representatives of different generations. It was a veneration of queer bloodline as an artistic gesture.

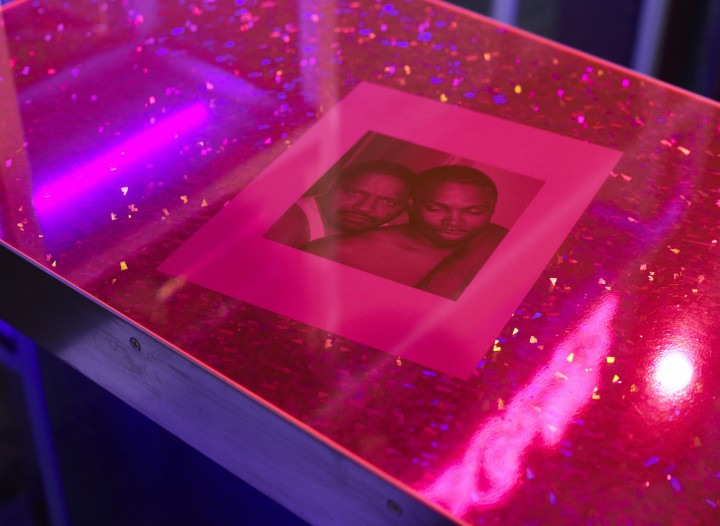

Part of the Phone Home project at the Museum of the African Diaspora consisted of speakers, televisions, computers, headphones, and stereos all covered in holographic car paint. The spark attributed a certain value, transforming these obsolete technologies into trophies and cultural beacons of the West Coast.

Attached to these structural installations were elements similar to photo albums: scrapbooks from children’s souvenirs and photographs of friends, family, and neighbors. These images are surrounded by bright pink color, signaling the emergence of a kind of feminized memory that remains authoritative despite its symbolic girlish nature (which is always read as frivolous) – a decisive rejection of the tradition of masculine black memorization.

These two projects, within her practice of large-scale installations, are ideally enclosed in what she describes as the boundary space “between the monument and the altar.”

If the monument is dedicated to celebration and remembrance, the altars are an offering to the forces that govern the present and the future, since they are necessarily associated with the past: temporal connection and interdependence. She maintains a clear emphasis on intergenerational communication in both directions of work.

At Phone Home, we see a spectrum of age and family relationships (both biological and non-biological) represented in the photo albums she creates, as well as a multi-generational representation of technological forms.

The use of a high-gloss finish is also reminiscent of the automotive and bicycle culture: breaking out of the familiar and personal.

It engenders a beautiful projection and reflection of Black’s object relations both in the recent past and in some magically liberating Afro-future. Her Afro-futuristic imagery is tuned to the soundscape.

The New Eagle Creek Lounge has been specially designed to accommodate queer elders, which is not always the case at queer gatherings.

She hoped to offer leisure and pleasure to young queer and transgender people, as well as a place for nostalgic bar patrons. Because surviving the AIDS epidemic in San Francisco is like surviving a war.

Traditionally, the bar was converted into a parade area and was featured at the San Francisco Pride Parade on June 30, where participants rode an electric slide like her father did in the 90s.

By extracting the archive from its standard physical and metaphorical one-dimensionality and transforming it into a three-dimensional sculptural one, Sadie Barnett offers us news-based ways of presenting and visualizing our memories.

Through this reconfiguration of memorization, we could imagine Black’s more dynamic ways of knowing and imagining.