On 27 February, Christie’s Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale in London will include standout pieces by Edgar Degas, Claude Monet and Pablo Picasso. Degas’ Dans les coulisses, thought to have been executed between 1882 and 1885, is a snapshot of life at the opera in the midst of a modernising Paris; Monet’s Prairie à Giverny, executed around the same time, attests to the vitality of rural France in the face of technological change; Picasso’s Le coq saigné, painted in France more than 60 years later, may be read as an attempt to work through the traumatic events of the Second World War.

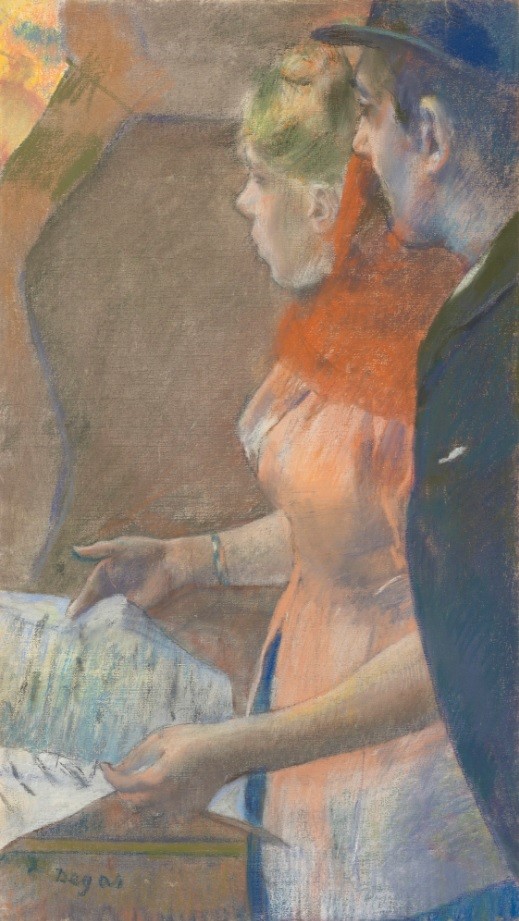

Perhaps no other artist is as closely associated with the performance arts as Degas. Dans les coulisses transports the viewer to the world of the Paris Opéra, which opened to great acclaim in 1875. Degas was a frequent visitor, and the Opéra became one of his favoured subjects.

As Dans les coulisses attests, it was not the stage but the wings that fascinated Degas. Here he could capture dancers waiting to go onstage, their unselfconscious poses far more expressive than their practised routines. And he could depict the shadowy figures known as the abonnés : male members of France’s elite who, after paying a subscription fee, enjoyed unrestricted backstage access.

Dans les coulisses brings the viewer directly alongside one of these men, who stands in extreme proximity to a blonde-haired girl who is about to perform. The flat plane forces the figures into the extreme foreground in an unequivocally modern composition. Although they are not overtly interacting, something about the pair’s closeness alludes to a more intimate acquaintance. This visual ambiguity characterises the greatest of Degas’ works, and his radical pictorial construction — extreme cropping, audacious viewpoints and often theatrical staging — charges these everyday views with subversive meaning.

From the 1880s, Degas increasingly left oil paint behind, preferring the immediacy of pastel. With pastel, he could perfectly convey the fragmentary nature of life in the modernising metropolis, and the inherently ephemeral quality of opera life.

After moving to Giverny in 1883, Claude Monet consistently sought inspiration in his new surroundings. Perhaps the most frequent motif he explored during this period was the expanse of pasture known as La Prairie, which he captured en plein air in virtually every season, tracing the annual cycle of growth and harvest that characterised this corner of rural France.

In Prairie à Giverny, painted in 1885, the meadow that fills the lower half of the composition is rendered in thickly impastoed, richly coloured strokes of paint, while the profiles of the towering poplars in the middle ground are captured using short diagonal strokes. Focusing on the life cycle of the field and its surrounding trees, Prairie à Giverny is an important precursor to two of Monet’s most celebrated series of paintings from the 1890s: the Haystacks and the Poplars.

There is a distinct sense of spontaneity in Prairie à Giverny, the brushstrokes suggesting the speed with which Monet sought to capture the fleeting effects of light. In this way, the work asserts Monet’s renewed dedication to Impressionism at a time when many of the movement’s pioneering members were abandoning it. The lush foliage also stands as a testament to the health of France’s agrarian traditions in the face of political, cultural and technological developments.

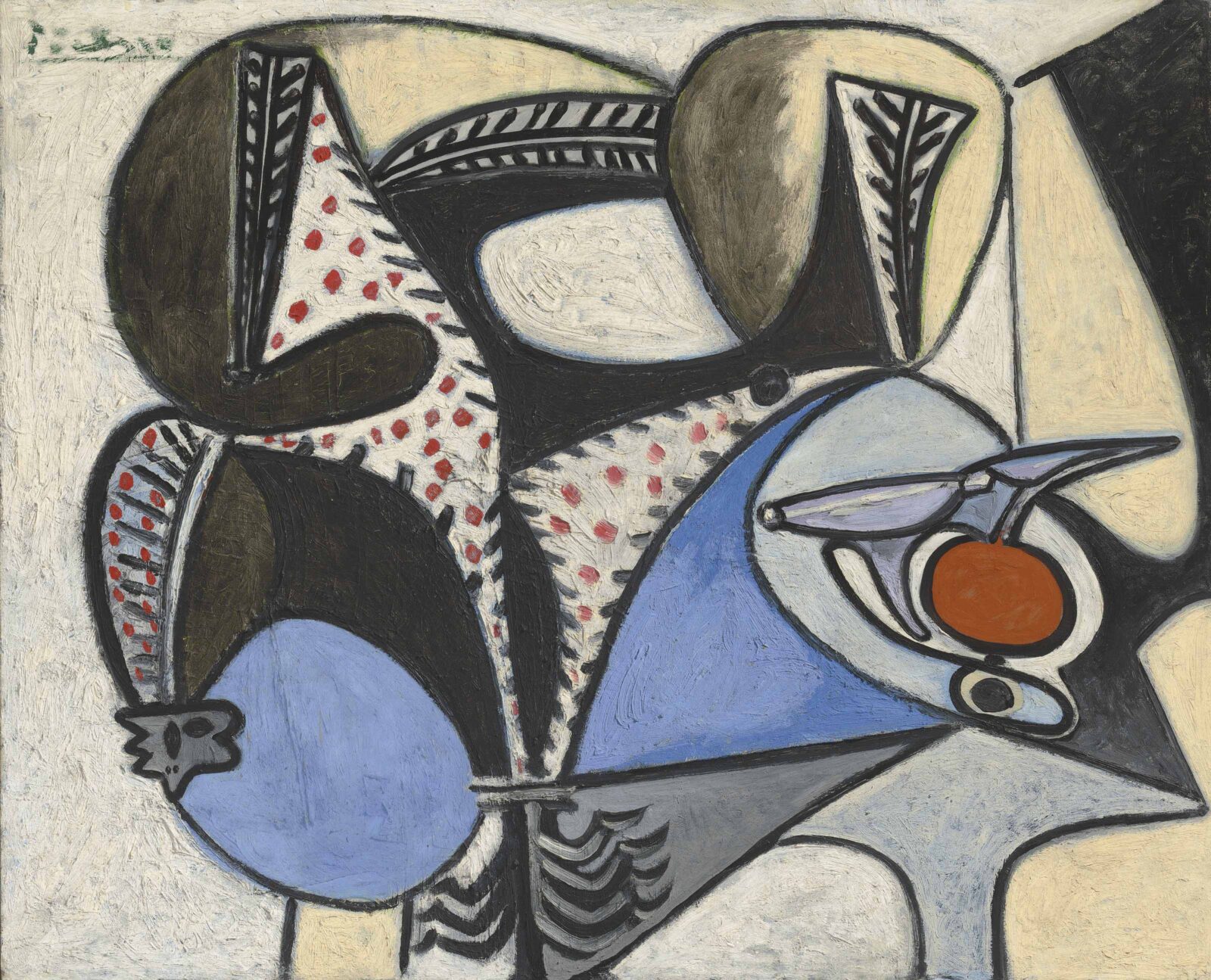

Picasso’s Le coq saigné, begun in February 1947 and finished in October 1948, is one of the most arresting still lifes the artist painted during and immediately following the Second World War. Its web of lines and composite colour planes conceal the sinister subject matter: a rooster with its throat cut, its neck hanging lifelessly from a tabletop. To the right, a knife balances on a bowl filled with what appears to be blood.

One of three works from this time that depict this subject, Le coq saigné is the most abstract. By the time Picasso began Le coq saigné, the rooster, with its connotations of virility, had become a favoured motif for the artist; it featured regularly in his work throughout the late 1930s and early 1940s. Recognised as a national emblem of France, where Picasso had remained throughout the Second World War, the rooster symbolises the indomitable French spirit.

In Le coq saigné, the animal is dismembered and lifeless — representative, some have suggested, of the trauma from which France and the rest of the world was still recovering. At the same time, Picasso’s use of abstraction transcends the symbolic violence of the subject. Leaving behind the despair of the war years, Picasso immerses himself in the expressive power of colour and form, looking forward to a new era of hope and possibility.

The painting also boasts a distinguished provenance. In 1951, just a few years after completing Le coq saigné, Picasso met Spanish painter Antoni Tàpies. An ardent admirer of Picasso’s work, Tàpies subsequently acquired Le coq saigné, and considered it the standout work of his large and diverse collection.