After last weekend’s much-anticipated Art Basel fair in Hong Kong, the lively interaction between art sellers and collectors continued this week at Christie’s auctions at the same Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre. The evening auction of “20th & 21st Century Art” on May 24 ended with a combined result of $204.2 million, well over the estimate of $141.7 million. During the five-hour auction marathon 97% of the lots were bought, and both Western and Asian artists were sold.

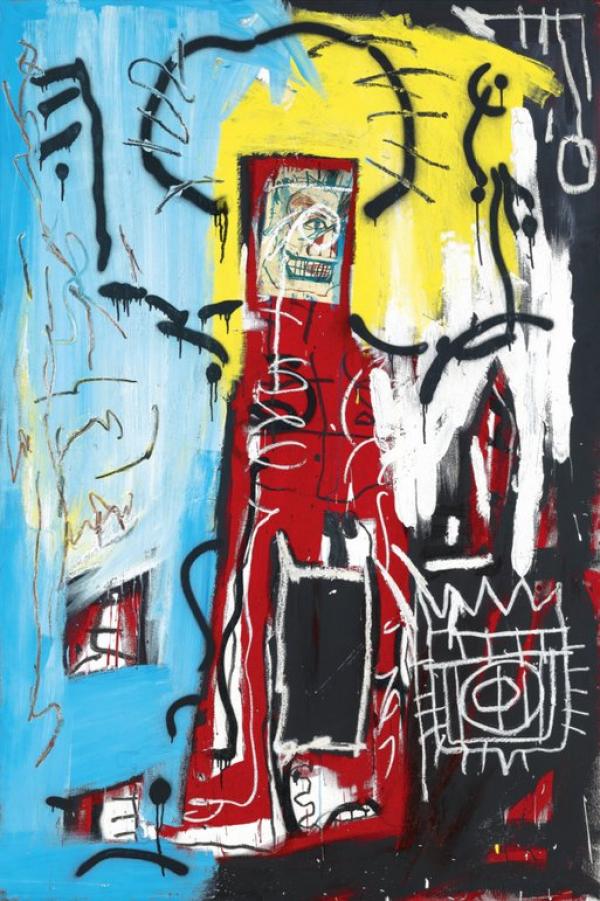

Top-lot has already established this spring tradition was the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat. After impressive results In this case ($93.1 million) and Versus Medici ($50.8 million), shown in New York auction in mid-May, for a painting by Basquiat “Untitled (One-Eyed Man, or Xerox Face)” this Monday in Hong Kong disputed from $15.5 million to $30.2 million. The work on behalf of his client acquired the president of Christie’s Asia Department Francis Belin. The last time this work changed hands was in 2017, when it fetched $14.6 million.

It is a painting with the caption “Untitled (One-Eyed and Xeroxed Face),” created in 1982. The work is on a canvas measuring 182.9 by 121.9 cm in acrylic, oil as well as aerosol paints with a collage element.

It is specified that the estimated value of this work was $ 18-22 million, while the name of the buyer is not disclosed.

The last time this painting was auctioned in London in 2017 for $110.5 million, which was a record price for auctioned works by American artists. In 1987, during the author’s lifetime, the work sold for $23,100.

On May 12, it became known about the sale of the painting Basquiat “In this case” for $ 93 million at Christie’s auction. The winning bid made by phone, it was $ 81 million. taking into account all additional payments from the collector required to pay $ 93.105 million.

On May 14, the painting “Woman sitting by the window” (1932) by Spanish artist Pablo Picasso was sold at auction in New York for almost $ 103.5 million.

Otherwise, the emphasis at Christie’s Hong Kong auction was more on well-known representatives of Asian modernism and contemporary art, rather than on Western names. In addition to Basquiat, among the most expensive lots were a scroll by Zhang Daqian titled “Temple on a Mountain Top” ($27 million), a still life by Chinese-French modernist Sanyu “Chrysanthemums in a Pot” ($13 million) and an abstraction by Zhao Wuji “24.01.63 ($9.8 million).

Contemporary works by Beijing artist Liu Ye, who has been represented by David Zwirner for a couple of years now, sold for good prices: one of Liu Ye’s paintings – “Hope No. 1” – Amoako Boafo, Matthew Wong and Salman Tour, whose works sold for $1.3 million, although not record-breaking, but still fared well – selling for three to nine times above the estimate.

Auction house sold two paintings by British street artist Banksy for just over $8 million at an auction in Hong Kong. According to the auction house, the painting “Sale ends today” was sold for 47 million Hong Kong dollars ($6.06 million) and the painting “Hummingbird” was sold for HK$15.9 million ($2.04 million). This auction was not a record for Banksy’s work. Recall that the record was set by his painting “Devolved Parliament,” sold at Sotheby’s auction in October 2019 for £9.9 million ($12 million).

A total of 73 works by various artists were presented at the auction of works of art of the 20th and 21st centuries, held in Hong Kong on May 24.

Jean-Michel Basquiat

When Jean-Michel Basquiat was three years old, he decided he was going to be an artist. At 12 he painted his first work, at 20 he sold his first painting, and at 27 he died of a heroin overdose. We tell you how he turned his whole life into an art performance.

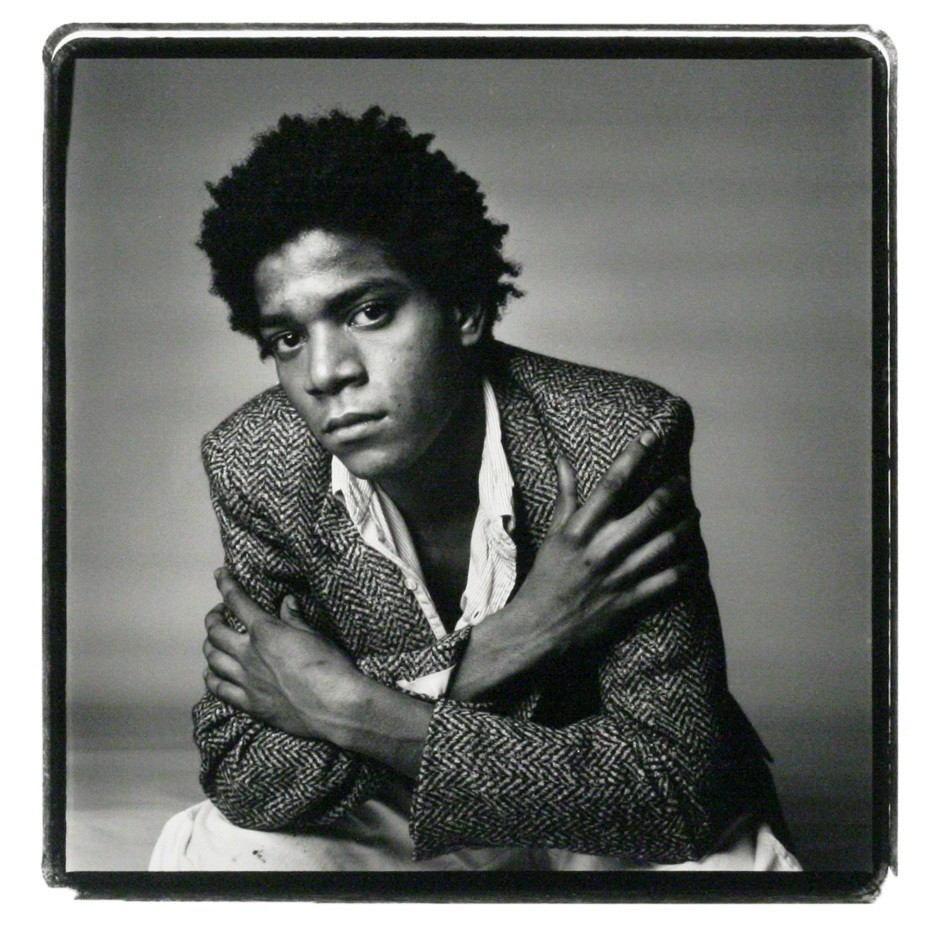

“Do you think you’re lucky?” – asks Basquiat Lisa Licintra Ponti in an interview with Domus magazine in 1984. “Also talented,” answers Jean-Michel. When talking to the press, he was not much of a talker, but he was not modest either. Basquiat knew his price even before his paintings began to bring him a lot of money; but by the mid-80s he was already the most sought-after artist in New York.

“In just nine years of active work, he left us a legacy that other artists can’t create in a lifetime,” said art dealer Tony Chafrasi in an interview with New York Magazine after Basquiat’s death. The artist would cover any object he could find: a refrigerator, a baseball helmet, the doors of a bookcase or the Armani suits that came into his closet with his first big paychecks. And it all became works of art.

He was called Black Picasso, although Basquiat himself did not like this definition: “On the one hand, of course, it’s flattering, but on the other it’s humiliating. He preferred to be himself because he was aware of his uniqueness: before Basquiat, no gallery in Manhattan had represented the work of black artists. And he fought this with his own methods, often akin to sacred rituals. One Thursday in 1982, Jean-Michel and his lover Suzanne Mallouk went to MoMA, where Basquiat pulled a bottle of water from his coat pocket and began sprinkling it in each room. “I would pee here if I were a dog,” Jean-Michel said as he walked past works by Pollock, Picasso, Klein and Braque. – Not a single black artist in this museum!”

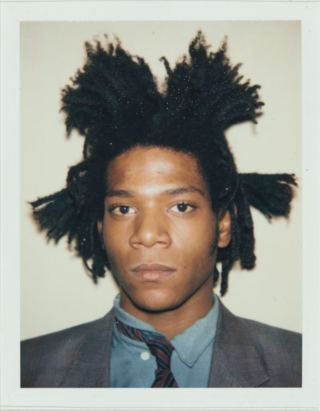

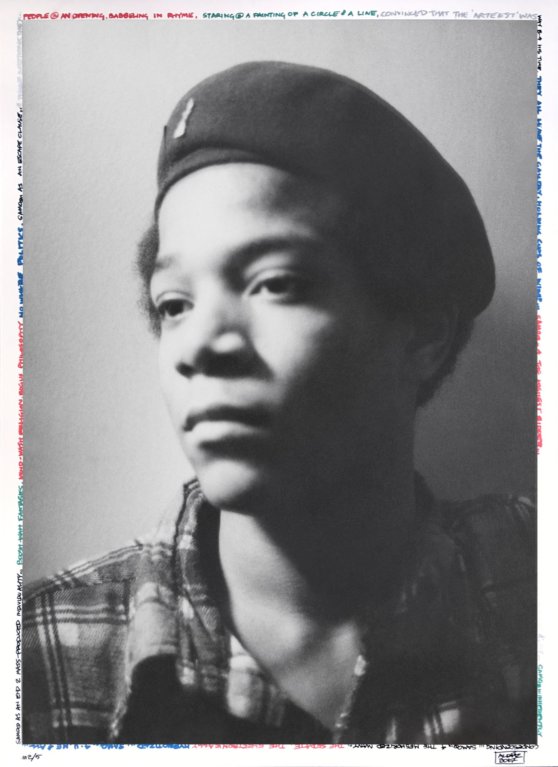

He hated talking to journalists: “They all write about my ghetto childhood,” Basquiat said. – For some reason they don’t invent childhood for white artists. In fact, he didn’t have a canonical “ghetto childhood” – his father, Gerard, made a pretty good living as an accountant, and his mother, Matilda, took her son to theaters and exhibitions at the Brooklyn Museum, MoMA and Met from a young age. It was she who instilled in Basquiat a love for art and fashion, so even in the SAMO era (when Jean-Michel painted graffiti on the streets of New York) he was always well dressed – in long wool overcoats, white short-sleeved shirts and classic straight-cut pants. He rarely wore accessories (more often he experimented with his hair), but, judging by the early photographs of Jean-Michel, he occasionally wore his vaifarera glasses and a Kangol beret.

In the early eighties, Manhattan started talking about him. Basquiat began to gain popularity and enjoy it. In clubs and bars, models threw themselves into his arms. In restaurants he ordered only the most expensive wine. Basquiat played the game of wealth, and his refrigerator was always stocked to the brim with profiteroles, eclairs and all kinds of delicacies. “I don’t know why he always bought expensive food,” Suzanne, who lived with Basquiat in the Crosby Street loft for several years, recalled in her memoir Widow Basquiat. – I guess he thought that’s what rich people do.”

“Jean-Michel suddenly turned into what he himself was most critical of – a flamboyant representative of the art scene,” said his close friend and legendary graffiti artist Keith Haring. – But what set him apart was that he didn’t take money seriously: he painted on designer tuxedos, lent fabulous sums of money to others, and threw hundred-dollar bills out the window of his limousine.

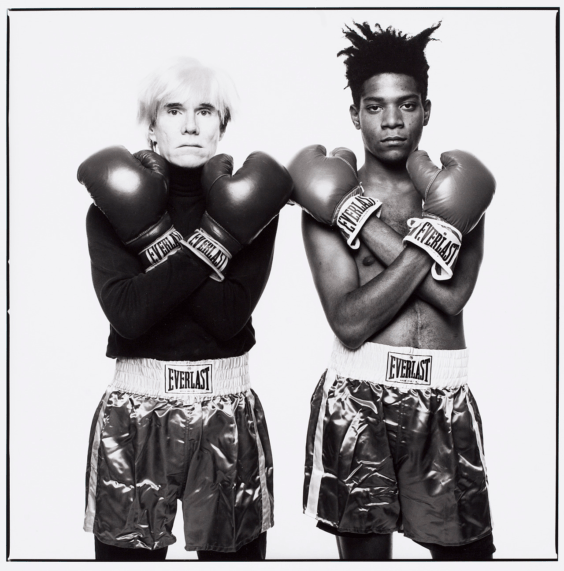

Basquiat even inspired those whom he himself once called his idol. For example, Andy Warhol and Rei Kawakubo. Andy admired everything in Jean-Michel: his works, his style and even the number of sexual partners (although Warhol was little interested in sex himself). And Rei Kawakubo invited Jean-Michel to take part in the Comme des Garçons Homme Plus spring-summer 1987 show. During the show the artist appeared on the catwalk four times and was the only model who never smiled.

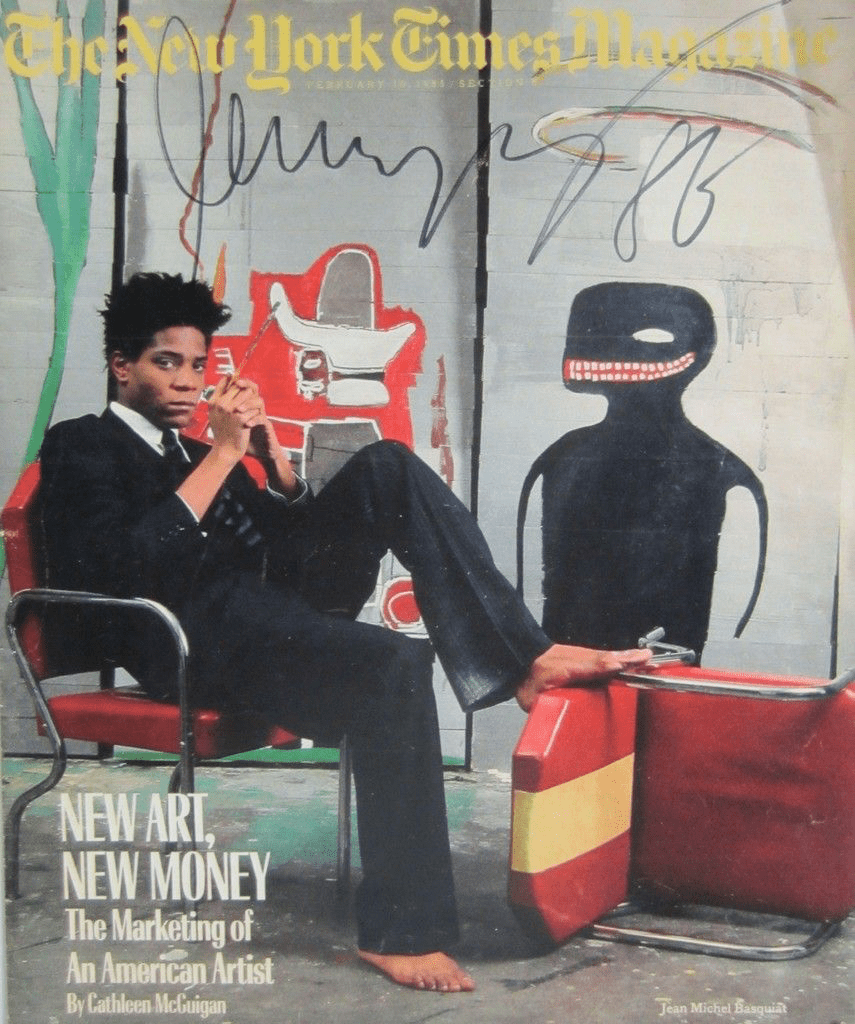

He is not smiling on the cover of the New York Times magazine either, posing barefoot and in a black Armani suit. The brand’s tuxedos became a kind of Basquiat uniform. He wore them to exhibition and party openings and painted pictures in them (and then often threw them away). “I was happy that he decided to wear my brand,” recalled Giorgio Armani. – And I was even happier that he drew in them. I make clothes to be worn, to live in, and he felt that.”

“Uniforms” did not kill individuality – on the contrary, the image of the barefoot artist in an expensive suit drenched in paint first became recognizable and then iconic. Moreover, despite the abundance of expensive suits, the artist’s closet also included vintage Adidas T-shirts, jeans (also splattered with paint), colorful socks and African national clothing. “He liked to shock,” Suzanne says. – “Sometimes with a red Mexican hat and sometimes with a traditional African shirt, which he wowed everyone with at the grand opening of some exhibition where everyone was in tuxedos.

“I remember when he was dating a blonde from a good family, he would dress like a dandy, like a Kennedy,” Mallouk recalls, “but just one detail was enough to ruin that image, and in Jean-Michel’s case it was the dreadlocks. The kind of dreadlocks you wouldn’t see on anyone else.” Especially in the privileged (i.e. exclusively white) environment of ’80s New York. “One day he went to another Italian restaurant,” recalls Jennifer Clement, author of Widow Basquiat. – There were 20 white businessmen sitting at a nearby table. They stared at him, made racist jokes, pointed a finger at his hair and said he was a pimp. Then Jean-Michel called the maitre d’ and told him that he would close the bill for these businessmen. He paid three thousand dollars for their dinner. So he laughed back at them.”

Basquiat also had no respect for those who were willing to pay for his work. He could kick a potential customer he didn’t like out the door or throw granola on his head from the window of his loft. And sometimes he would send his lovers to “business negotiations” and lock himself in the bathroom. Once popularity came into Jean-Michel’s life, with it came many fears. “He had particularly frequent panic attacks when he was on drugs,” Jennifer Clement recalls. – He was afraid that his fame would prove to be a passing blip. He was afraid he would be killed by the Ku Klux Klan or the CIA because he was popular and dark-skinned. He even installed a sophisticated alarm system in his loft.”

Drugs ruined him. Friends of Basquiat recalled that the situation worsened markedly after the death of Warhol in 1987 – the mentor, best friend and collaborator of the artist. The loss was followed by depression, followed by more and more doses. It was then that Jean-Michel met his latest lover, Kelly Inman, who worked at Nell’s Club in New York and treated him to dessert. Thus began a romance between the artist and a waitress. Kelly lived with Basquiat in a loft on Great Jones Street and, as friends of the couple recall, tried to save him from his addiction. “He usually slept all day,” Phoebe Hoban wrote in the New York Times a week after the artist’s death. – Kelly went up to his room at 2:30 to check on him. Basquiat was sniffling in the huge bed. Three hours later, Kelly went back into his room because someone had called him. This time he was lying face down on the floor.”

“I’m not a person. I am a legend,” Jean-Michel Basquiat said of himself. And when he was gone, the artist’s friend and art dealer Rene Ricard (author of The Radiant Child in Artforum magazine, after which Basquiat was first talked about) told the New York Times, “Jean-Michel was blessed by God himself. He was one of the black saints. Martin Luther King, Hagar, Muhammad Ali and him, Jean-Michel Basquiat.