Breughel (1525/30 – 1569) is often referred to as Hieronymus Bosch’s successor. Yes, at first glance, part of their work is similar. Breughel, just as Bosch created the crowded canvases.

But still, they’re different. As the artist and writer Maxim Kantor accurately noted, they are as different as Malevich and Chagall. Both are avant-garde. But one is about squares, the other is about love.

Bosch is a medieval surrealist. He has a lot of monsters from terrible dreams. Brueghel is a realist. He has ordinary people, townspeople, beggars. Strange creatures in his paintings are very rare.

Bosch has refined, thin figures. Bruegel has messy peasants. It was Michelangelo who influenced Bruegel, rather than Bosch.

Bosch is about fear of falling into sin. Bruegel is about human foolishness and vanity of life.

There’s too much difference to put Bosch and Bruegel in the same row.

Here are just a few of Bruegel’s masterpieces. They’ll help you get to know a unique painter like Peter Bruegel Sr.

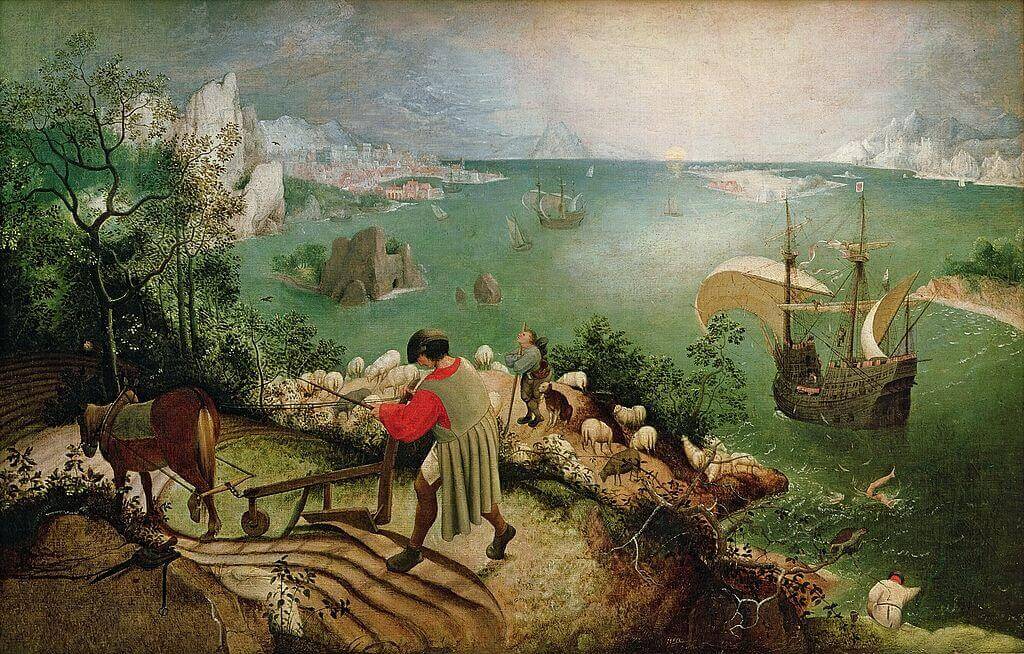

1. Landscape with the Fall of Icarus, c. 1558

The painting is called “The Fall of Icarus.” But where is the Icarus itself?

In the foreground, the ploughman. In the middle is a shepherd with sheep. It’s a ship. In the distant one, the sea and the mountains.

Ah, yes, in the lower right corner between the fisherman and the ship – the Icarus who fell into the sea. He’s almost immersed in the water. Only his legs can still be seen. And there are several feathers circling around.

Why so much disregard for the protagonist?

It is believed that this is how Bruegel illustrated the folk wisdom of “No plough will stop until someone dies”.

Bruegel portrayed the death of a young man without anyone noticing. No fisherman, no ploughman, no shepherd. None of them left their class. The ship sailed past, too. This world’s indifference to one man’s tragedy is discouraging.

That was Braegel’s world. Has it changed since then?

2. The Dutch Proverbs. 1559 г.

It’s an amazing picture. 119 illustrations for proverbs.

Some scenes can be easily deciphered without knowing Flemish folklore. Others without that knowledge you won’t understand.

On the left fragment, a man carries a basket of steam. It’s obviously a pointless case. The saying “carrying steam in a basket” means “wasting time.”

But on the right side, a woman wears a blue cape on a man. There is no logic to modern man. In Bruegel’s time, it meant cheating on your husband.

There are a few Bosch-like monsters in the picture, too. But only to illustrate the proverbs.

On the left, we see a saying about people who “can even tie a line to a pillow”, which means being very stubborn. On the right, we see a comrade who “holds the devil’s candle,” which means he is ready to flatter and be friends as long as there is the benefit. And another one is “Confessed to the Devil”, which means he’s a traitor. He reveals secrets to the enemy.

The second title of the painting is “The World Upside Down.” Bruegel showed the world of men by exposing all its vices. A world where people do meaningless things. A world where people are friends for profit. A world in which treachery at every turn.

Bruegel’s vivid satire. Funny and sad at the same time.

3. Pieter Bruegel The Tower of Babel. 1563

The “Tower of Babel” combines panoramic and miniature painting in an incredible way.

The details of the painting are astounding. Try to find these fragments of the middle plan. A challenge for most patient.

On the left is a 16th-century crane. On the right is a part of the city behind the Tower of Babel. There’s a cart driving over the bridge, women rinsing their underwear.

And you can also see that the walls are full of lumberjacks. But judging by the women’s figures and the hanging lingerie, the families of workers have already moved in. It looks more like an anthill than a majestic tower.

Don’t you think it’s still strange that construction is going on at almost every level? It would seem that the lower levels should be completed by now, and the work should be done only at the top.

But no, there’s work going on everywhere. Obviously, people don’t understand each other much. So they can’t agree on the best way to build a tower.

But they manage to preserve the integrity of the building. And even live in it with their families.

Despite the misunderstanding of each other, in the end, we manage to preserve our fragile human world. All in patches, all in scaffolding. But it keeps standing.

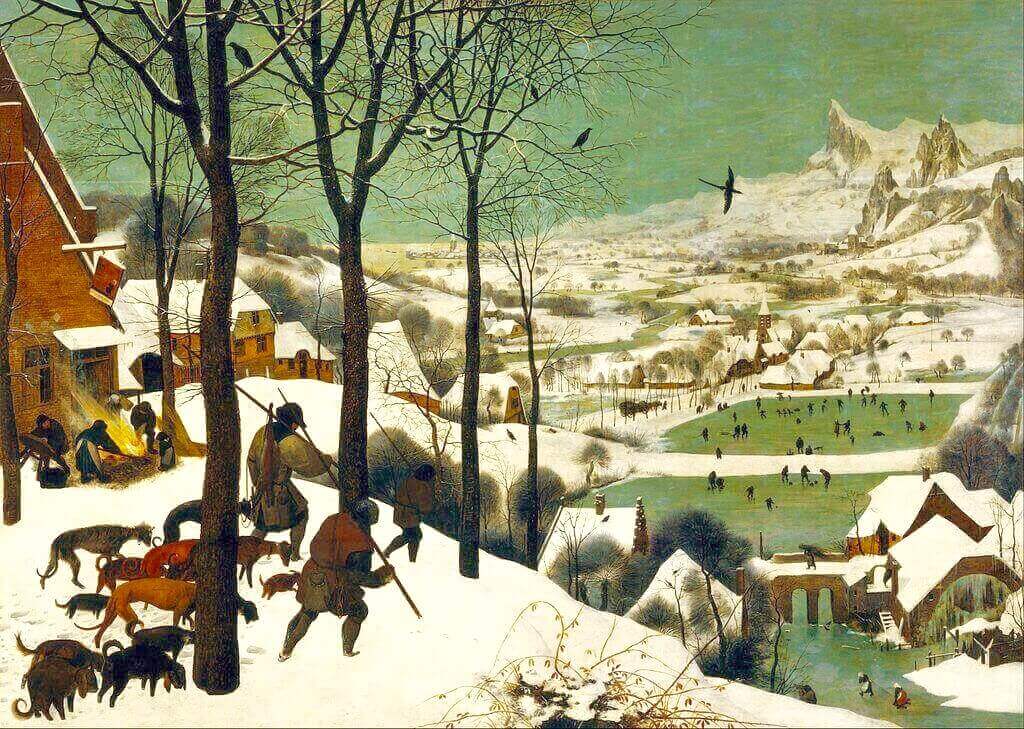

4. Pieter Bruegel The Hunters in the Snow. 1565

“The Snow Hunters” is one of the major masterpieces of the Renaissance. What’s so special about it?

The painting’s space is slightly concave inside. It’s as if it’s painted on the inside of a giant bowl. The effect of an incredible, “sucking” depth.

Of course, Brueghel deliberately distorts the perspective. Otherwise, he wouldn’t be able to fit everything in such a confined space.

As in the Tower of Babel, Bruegel is working on every detail. Zoom in on any part of the painting, and you have the whole work of art in front of you.

Did you know that Snow Hunters has a fire scene and a curling game? It all happens in the background.

In this masterpiece, there is no longer the satire of “Proverbs”, the tragedy of “Icarus” and the beautiful legend of “Tower of Babel”. But there is a picture of the world where man and nature coexist quite well.

An unexpected philosophy for the time in which Bruegel lived. That’s when America was discovered. People were becoming more and more convinced of their own superiority. And they thought less and less about being united with nature.

That was Bruegel. He rarely thought in unison with his age.

5. Peasant Wedding. 1568

“Peasant Wedding” is one of Breughel’s most joyful paintings.

Apart from him, no one else depicted the peasants. Just imagine, such a picture was created when painted exclusively goddesses and aristocrats!

The painting is also densely populated. But here we see much more unique faces. With individual features. These are no longer caricatures of “Proverbs” or generalized images like “Hunters”.

What else do you see as unusual? You don’t see anything else, do you? Where’s the bride and groom?

The bride in a black dress with a thin wreath on her head. She’s so happy, she’s got her eyes covered. But it’s harder to find the groom.

This painting also makes it easy to understand Bruegel’s special style. Look at the way he uses color. It’s a red jacket. It’s a white apron. A green carpet. No complex shades or layering.

It’s amazing. After all, Bruegel did it when the mannerism was already taking shape. When pretentiousness and stylization were highly valued. But Bruegel preferred complicated things to be told in simple language.

6. The parable of the blind. 1568

“The Parable of the Blind” is one of Bruegel’s latest works. He died in 1569, having lived about 40 years (the exact date of birth of the artist is not known).

We have six blind men holding on to each other. The leader had already fallen into the pit, followed by his comrade. The others are on their way. The last ones don’t know what happened yet. But we already know what’s going to happen to them.

Morality is simple. It’s in the Bible, “If a blind man leads a blind man, they’ll both fall into a pit.”

We can see a line of blind men in the Flemish Proverbs. Only there you can barely tell them apart.

So what made Bruegel dedicate an entire picture to this story?

The answer can be found in Dutch history.

It was the hardest time in the history of the country. A revolution had just begun, the aim of which was to gain independence from Spain.

But the contradictions were tearing the Netherlands apart from the inside. Someone was loyal to the Spanish king. Somebody was for independence. One wanted to remain Catholic. And his neighbor wanted to make the country Protestant.

Dozens of leaders were pulling followers. And led them to their deaths. They burned on the fires of disloyal to the king. Killed Catholics. The Protestants were executed.

That’s “The Parable of the Blind”. This is Braegel’s warning, his will to future generations. No right and wrong. Don’t be a blind man who thoughtlessly follows the brave and loudly-voiced, but essentially the same blind man.

The Hermitage holds a copy of Peter Braegel Jr.’s The Worship of the Magi.

The original is kept in Switzerland. The son did not always copy one into one of his father’s paintings. So it’s interesting to compare them, too. Try it.

Like in “Icarus”, you will not immediately find the main characters in “The Worship of the Magi”. They are lost in the daily routine of the town.

In the lower-left corner, we can barely distinguish between Mary and the baby. Then we see a line of magi. And two camels carrying gifts to little Jesus.

Let’s sum it up about Bruegel:

Bruegel is an artist and philosopher. He should not be considered, but “read”.

In his paintings, he combines morality and love of life.

Bruegel was NOT a follower of Bosch.

Bruegel is unique. Because the main characters in his paintings are ordinary people. It’s only 300 years later that Millais and Van Gogh would dare do it.

Bruegel is a brilliant artist.