A couple of years ago, Susan Rothenberg noted she read that a group of ravens is called an unfriendly. She said it an erroneous characteristic because these birds, to her opinion, were “great”. They can somersault in the air. They solve puzzles invented by people. They chase hawks away.” Susan and her husband, the artist Bruce Nauman, always saw those wonderful and smart birds at their ranch in Galisteo, New Mexico, ravens began to trust them and let in. “It’s like having a wayward independent pet around,” she said.

Rothenberg died this week at 75, she spent her life making pictures like a raven: uneven and raw, they are secretive and uncomfortable. She changed animals and humans into psychic and symbolic energies

Horses were the first. In the 1970s she was an unusual and insightful artist in the city Manhattan art space but soon found she drawing in detail the horses on the back of a piece of paper. That year she painted the first pictures of horses. She represented three at a patchwork SoHo rotational space. She was amazed they would come to determine her practice, and they would help to become one of the shrewdest and most brave painters of our time. ( Get valuable advice from her: Trust your strange ideas. Trust yourself.)

Rothenberg’s horses are often in the action, run to or from this world. Their bodies are drawn on the contour, often filling up the color of their earthen backgrounds (sienna, ochre, rose), they gain relief and fullness. They portend disturbing events and moods: captivity, escape, the struggle between the inner and outer world. One black like shadow horse, called Cabin Fever (1976), is “about readiness to go to the unknown” Rothenberg once said.

The white horse in For the Light (1978–79)—a ghostly steed flying forward —looks like it could run over you. In a different reserve without the name 1978 piece, which is just dark lines on white, hands cradle a human head as it radiates light from her head.

Perhaps this is a cruel art. But it’s all about what happens in nature, in the real world. Rothenberg was showed survival, without malice. In Dogs Killing Rabbit (1991–92)— about 12-foot art owned by the Museum of Modern Art in New York—the former make out the latter in a red spray, tangerine, and earthen. Rothenberg said that everything happened in reality. She and Nauman were riding on the horse, and they tried to stop the fight by screaming at the dogs.

Her paintings can be viewed from different angles, and the creatures in the pictures seem to soar in the air (“I think some trial, most trial probably, can’t be showed from one point of view,” she once said.)

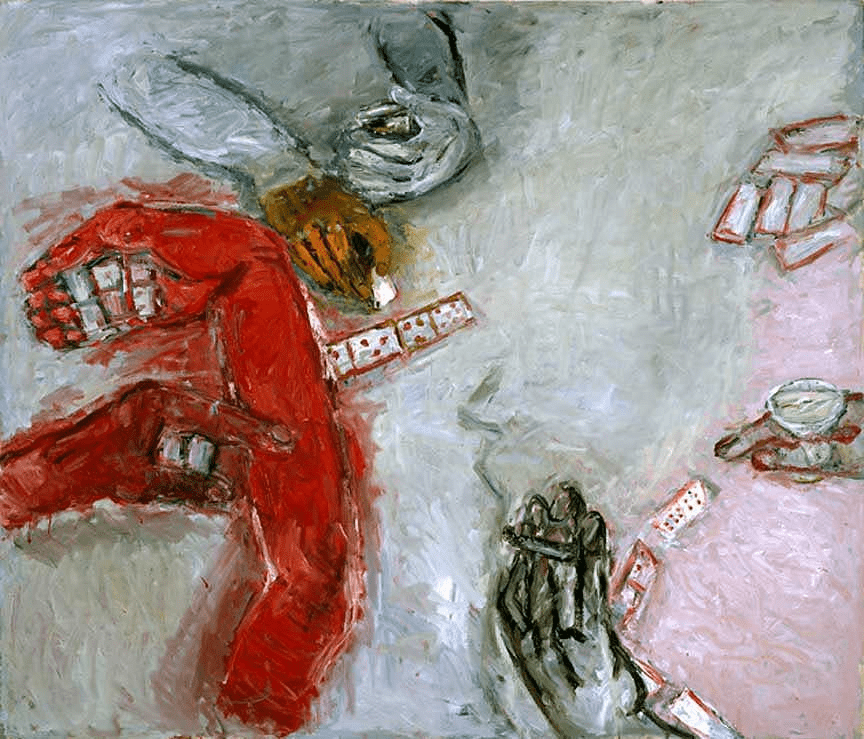

As easily as she transmits nature’s violence, Rothenberg could translate freedom, joy, and fun, as she did in the experienced player in dominoes in With Martini (2002), and the mixed figures in Blue Funk (2001–02). Her improbable 1985 portrait of Piet Mondrian dancing in a romantic and aesthetic golden light.

She never gave up. This was a painter who once recognized that “I don’t understand those persons who give up their dreamwork because they think that they will not succeed. It is necessary to try and work more in order to achieve a result. believe in yourself. And continue to do.”

One picture, the next picture, third, one hundred and third. And you will hear and understood. Rothenberg came back to animals like dogs and ravens time after time. Sometimes they looked menacingly, sometimes cute, provocative. One of Rothenberg’s

targets, she said recently, was “do not betray yourself in your desires and self-expression.” Some time ago she said a remark that seems like a conclusion: “be thankful to the world for what is happening to you»