There is a painting in this riveting exhibition of a child in a red muslin frock with puffed sleeves and a black velvet sash. The year is 1842. She might be any Victorian sitter, posing for her portrait with hands sedately clasped in her lap. But there are signs of strain in her sweet face, the feet are bare and her dark hair is cropped. Mithina is the child’s name, and she is an Indigenous Australian from Flinders Island off the coast of Tasmania. The painter is evidently a strange figure to her.

He is Thomas Bock (c1793-1855), and quite possibly unfamiliar to us as well. For Bock was a convict artist. He started out with a considerable reputation for engraving and miniature painting in Birmingham, where he lived, and is now being brilliantly revived by the city’s Ikon Gallery. On the evidence of his fine and sensitive images, he would surely have become a celebrated portrait painter.

But in April 1823, Bock appeared at Warwickshire Assizes charged with “administering concoctions of certain herbs to Ann Yates, with the intent to cause a miscarriage”. He was a married father of five; Yates was his pregnant lover. Bock was founded guilty and sentenced to transportation for 14 years. He arrived in Hobart, the capital of Tasmania, aboard the Asia in January 1824 – there are deft sketches of the prison hull, the convicts, the sailors working, or idling, all the way through the three-month voyage – and never returned to England.

Paper is scarce so the pictures may be small, but no less strong in their force of personality. Bock catches Sir John Franklin at a distance, the governor or Van Diemen’s Land deep in conversation in a knot of other colonialists (Franklin will later vanish on the expedition to discover the Northwest Passage). He notices the specially mischievous smile of a spear-carrying fisherman, and the keen anxiety in the intelligent face of a young Indigenous Australian womanabducted, and severely maltreated, by an English whaler. The images, one feels, often exceed the commission; Bock sees more than he is paid for.

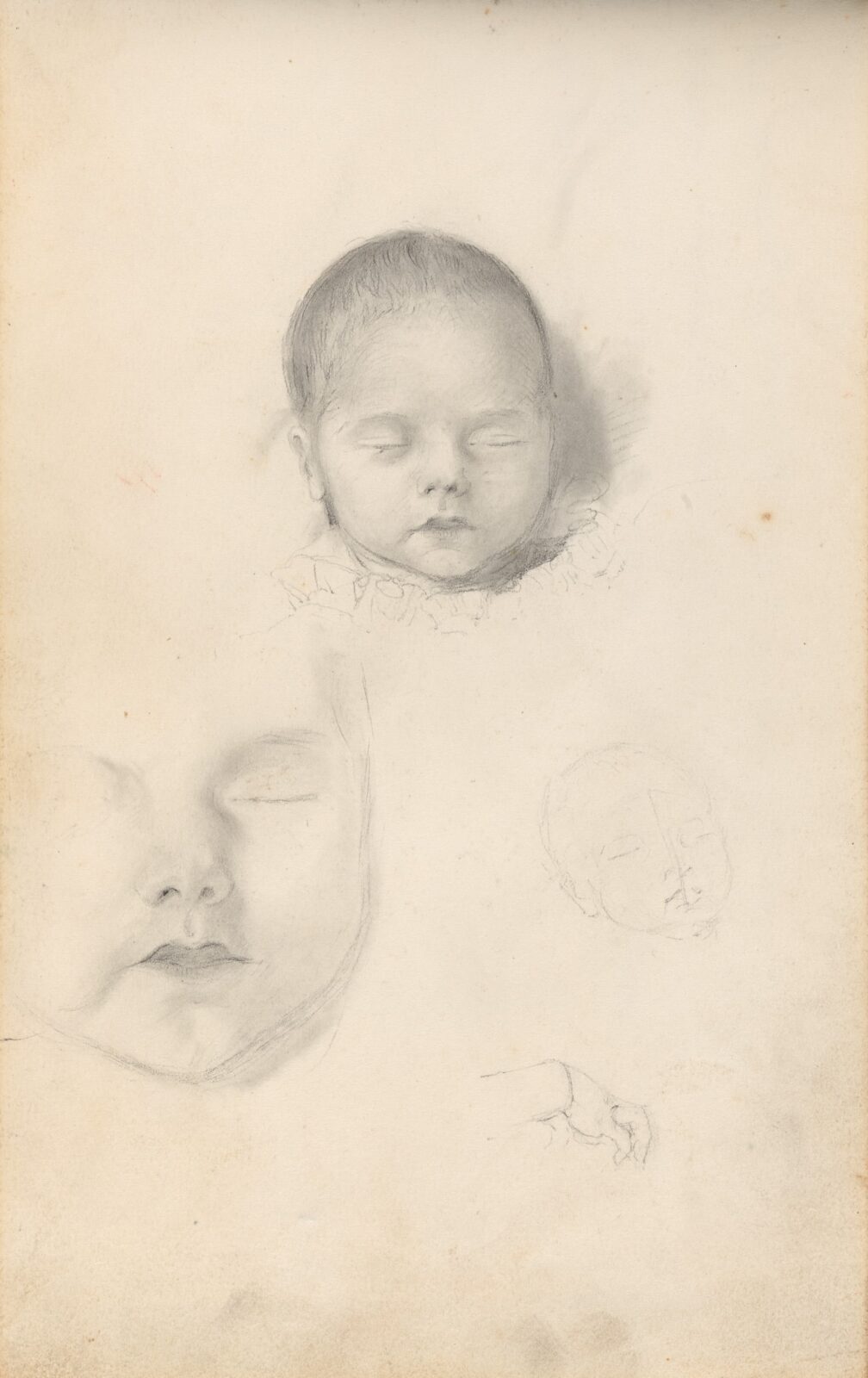

He was a pioneer in other respects too. Some astonishingly candid chalk nudes of his second wife (with whom he had another five children; his first family were all dead by 1845) attest to Bock’s endlessly tender line. And he made stunning daguerreotypes, the first in Tasmania, of which there is a case in this show. Double portraits capture the shadows of people from the long-ago past on tiny silver plates. Bock’s subtle eye for family affinities and close relationships immediately strikes home in these intimate objects with their burnished frames.

Empathy seems to me to be his legacy. An empathy for his fellow convicts, for the desperate white men thrust into this new world; but even more for those driven out by the colonists. His portraits amount to a memorial for an indigenous people dying out even as he painted and drew them. Bock is now described as an English-Australian artist, but that doesn’t seem quite right. For the best of his work surely belongs to Australia.