Branwell Bronte – portrait of his sisters: Ann, Emily, and Charlotte, circa 1834 (in the center he painted himself) / provided for exhibition at the Morgan Library and Museum / National Portrait Gallery, London.

The dress is floor-length, blue, with a white petals pattern, with small buttons on the corsage and a tight collar – small, sewn for a woman of 4 feet 9 inches (about 1.5 m). It was owned by Charlotte Bronte, and her modest day dress, which could fit a 12-year-old girl, was like a wrapping paper hiding a huge talent, a bubbling mixture of ambition, passion and literary genius. Like an ethereal spirit, the dress stands at the entrance to “Charlotte Bronte: An Independent Will”.

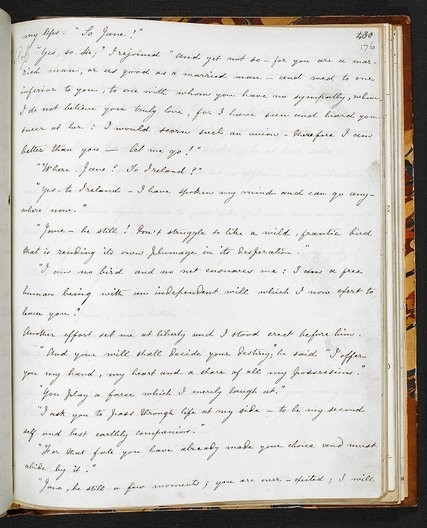

The central chapter of the novel about Jane Eyre, in which the heroine, deeply in love with Mr Rochester, the owner of the house where she works as governess, rejects his offer to live with him as a mistress. He asks her to stop bursting out “like a wild bird.” And she replies: “I am not a wild bird, and no net will hold me back, I am a free human being, with an independent will that now requires me to leave you.”

This passage – one of those that once amazed readers of the novel – can be read in the manuscript of the novel.

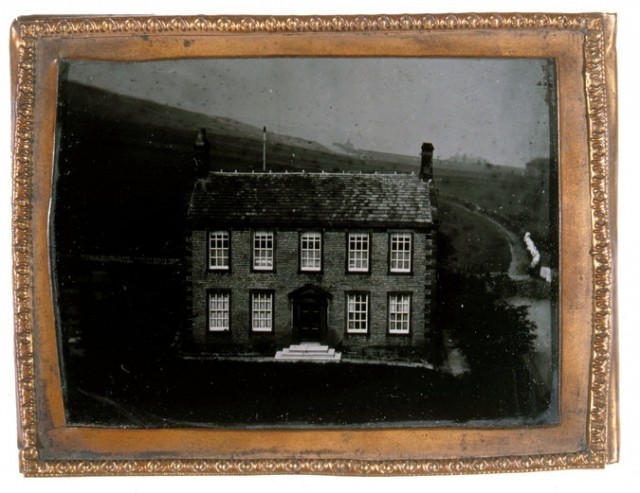

Christine Nelson, curator of the museum, received the manuscript from the British Library and, in addition, was allowed to borrow books, drawings and some other items from the National Portrait Gallery in London and from the Bronte Sisterhood in Haworth, Yorkshire. The exhibition, which traces the chronological movement in a circle, begins with the location. For almost her entire life, Charlotte lived in a modest house in Haworth on the edge of a wild marsh west of the industrial towns of Bradford and Leeds.

In the hands of the novelist Elizabeth Gaskell, whose incredibly popular biography The Life of Charlotte Bronte, which saw the light in 1857, two years after Charlotte herself died at the age of 38 years, the village, house and its inhabitants have acquired the same Gothic appearance in which they are usually drawn by public imagination. High on a hill blown by all winds, covered in darkness and continuous rain, there lived a family of creative geniuses with three little Wendy Addams – Charlotte, Emily and Ann – that’s what the notion of them still holds in the literary world.

The two souvenir postcards on display confirm the overall impression: a strict photograph of the pastoral house, with gravestones in the foreground, and a truly frightening ambrotype shows us a blackened, lonely house with frighteningly shining windows. He begs to be driven out of it by impure power.

In fact, Haworth was a busy village with 11 grocery stores and 6 pubs, one of which was just a few steps away from the pastoral house. And three sisters, along with their brother, Branwell, enjoyed living in this humble home, even though their mother and two older sisters had died. From a young age, the early siblings left the walls of their home, immersing themselves in the world of Gless Town, England and Gondala, a world of imaginary lands inhabited by aristocrats, poets and ardent lovers. And today romanticism at home in Haworth, where Byron and Scott were considered gods, is still strong.

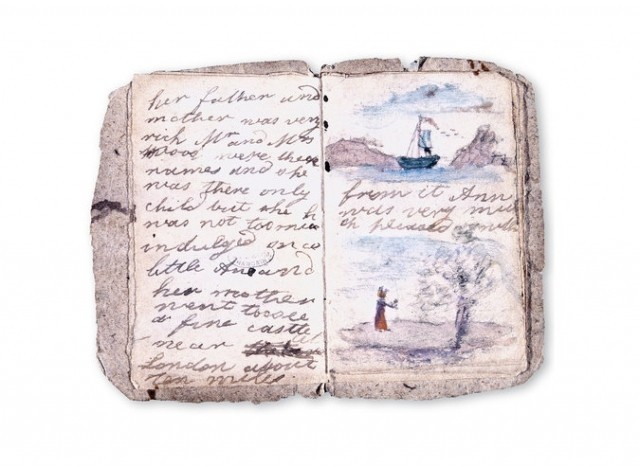

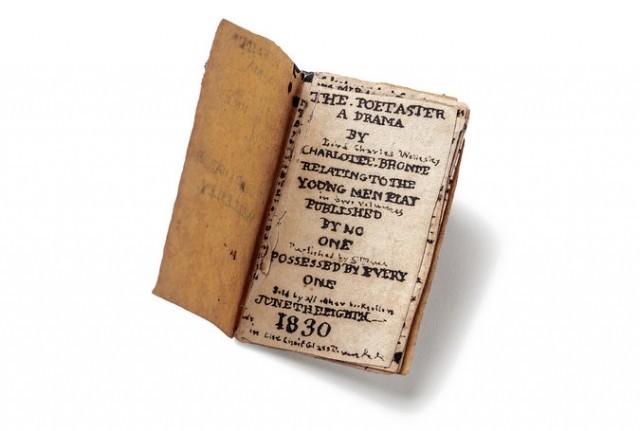

The 2nd chapter of Bronte’s exhibition history is remarkable in its form and content. Charlotte had almost microscopic handwriting, which, with the appearance of printed fonts, gave her publications the appearance of a completed book or magazine. The Young Men’s Magazine, a pretentious Blackwood’s style magazine, an inch by two, contained the table of contents, articles, and made-up ads. It was accompanied by reading magnifiers. The issue was small, but the ambition was enormous. Charlotte, paying tribute to prejudice, often imagined herself nothing but a village gray mouse, the daughter of a priest. But it was largely a disgrace.

Ms. Nelson came up with the idea of keeping track of the evidence. Pencil portrait of Zenobia, Marquis of Ellington – one of the characters of the fictional Glass Town, painted by Charlotte herself in 1830, is accompanied by sharp quotes. When Zenobia, who had great intelligence, just like the creator of “Jane Eyre”, gets criticized by the circle of men, Marquis Dorsky boils and stands on her defense: “Of course, you’re struck by the fact that a woman shows such amazing abilities that the useless fire of modern men pales in front of her.” As sisters approach their older teenage years, they begin to realize their limited prospects as daughters of a humble priest. They had to find work, and for single women in their class this meant only two options: to become either a teacher or a governess. Neither was suitable for their talent and temperament.

The saddest document is the sisters’ announcement of the school they had hoped to open: “Miss Bronte’s institution for the education of a limited number of young ladies”. And the number of young ladies who studied there was really limited: zero. Just a few years earlier, Branwell, a novice artist, created a group portrait, portraying himself with three sisters. This portrait also became an important point in the exhibition. It’s a rather strange visual document. On the one hand, Branwell depicted his own image, whitewashing himself and leaving his sisters as if separating himself from his family. In a way, that’s what happened. His life, driven by a suicidal spiral of alcohol and opium addiction, came to an end at 31. Tuberculosis took Emily at age 30, shortly after Wuthering Pass saw the light, Ann died at 29.

For more than half a century, the portrait, composed of four people, was kept on the top shelf of a cabinet in the house of Arthur Bell Nicholls, the vicar of Haworth, whom Charlotte married 9 months before her death. It was discovered by Nicholls’ second wife in 1916. It is now kept in the National Portrait Gallery and, like the manuscript “Jane Eyre” from the British Library, rarely leaves its place.

“It was very difficult to get them to the exhibition,” says Miss Nelson in an interview. – These are pilgrimage items. People come to the National Portrait Gallery in particular to see this particular portrait”. It’s sad to say, but Branwell wasn’t bothered with talent, and his portrayal of Charlotte gives very little truth about what she really looked like.

Another of the only portraits we know of her is an exquisite one painted by George Richmond, also from the National Portrait Gallery. Richmond was invited by Charlotte’s editor, George Smith, to create a flattering image of the writer, which was done.

The next generation unsuccessfully tried to find the image to compare it to a living literary personality.

By the time Charlotte appeared in the front row of Victorian literature with her novel “Jane Eyre”. In her short life she managed to create two more novels: The Town and Sherly, which together with her work The Teacher are on guard of the manuscript “Jane Eyre”. Everything else is already a story.

Admiration turned into worship a few years after Charlotte died. She died three weeks before her 29th birthday, pregnant with her first child. Her fire was in all its glory in Gaskell’s book. Readers of the writer’s biography and novels began visiting Haworth, wanting to see the famous marshes and the pastoral house with their own eyes.

A letter of 1858 from Patrick Bronte, Charlotte’s father, with a piece of one of Charlotte’s letters carved, in response to a request from an American admirer who was looking for a sample of the writer’s handwriting. A small stream of “pilgrims” – no more than 200 people a year in the 1860s – turned into a huge stream after the Bronte Museum opened in 1895 in several rooms above Yorkshire Penny Bank.

Today, small Heworth attracts around a million visitors a year, some going to the Bronte House Museum, which opened in 1928 to replace the first museum dedicated to women writers.

As one of the first columnists wrote: “Jane Eyre” – the novel, which makes the heart beat, and the pulse gallop. The same can be said of its author. And that is the most undeniable proof.