After Don Giovanni has just shanked the Commendatore, Leporello asks: “Who’s dead? You, or the old man?” It normally gets a big laugh. But WNO’s revival of John Caird’s production, directed by Caroline Chaney here, leaves this question hanging over the whole proceeding, with skin-crawling effect.

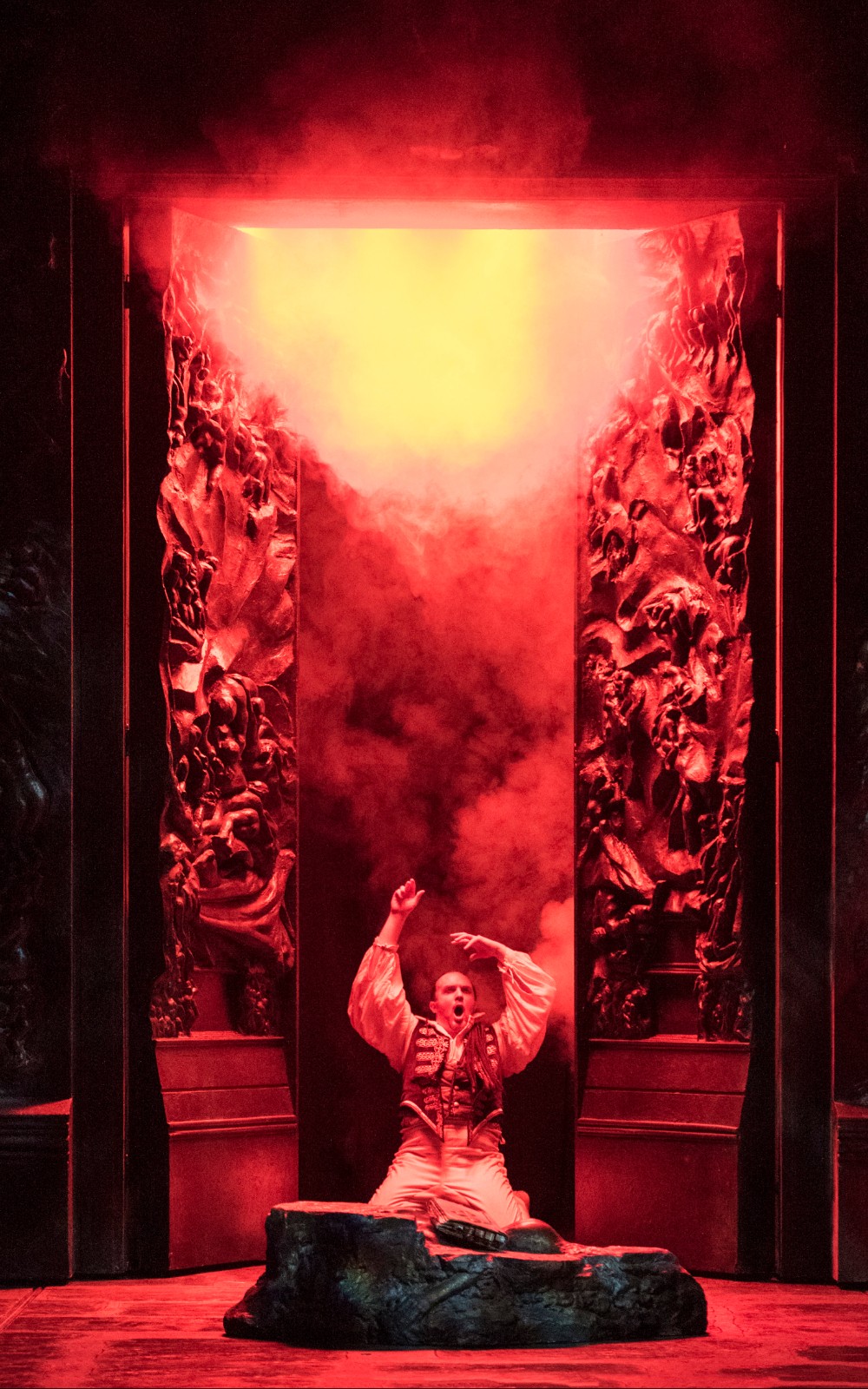

Costumes tell us we’re still in the 18th century, but sunny Seville is far hence. John Napier’s staging is designed around Auguste Rodin’s The Gates of Hell, his take on the opening scene of Dante’s Inferno. And it is these gates that will eventually open and devour Don Giovanni himself in the denouement. Rodin’s writhing figures – reflected in the movement direction too – were embedded into the shifting walls of a set that would enclose characters at moments of psychological interest, a canny reminder that it isn’t just Don Giovanni’s soul which is up for grabs. The characters – and the audience – all have one foot in Satan’s departure lounge.

Perhaps Don Giovanni was killed in the opening fight, and the opera that follows is the dark purgatory where he marks time till the final judgement, along with all the other lost souls of the piece? There was a sense of gloomy, existentialist inevitability pervading the whole thing. This was a literal gloom: the action took place in Stygian darkness – the point, I suppose – and could’ve used a bit more contrast at times. But one startling effect of this low-lighting was to make Rodin’s figures look like the ghoulish carved misericords of Northern European cathedrals.

There was plenty of excitement and movement though, particularly from the WNO Orchestra. James Southall led taut strings at tempi brisk enough to keep the drama moving; scenes would segue seamlessly, and Southall launched into the bottom-clenching opening chords of the overture before the audience had finished applauding. Gavan Ring as Don Giovanni has a flexible, aristocratic baritone with a strong core. His Don is one that sweeps about the stage in a magnificent coat and hat, vocally pirouetting between menace and charisma that infected everyone on stage. Leporello is often sleazy and craven, but David Stout’s version really did seem to stand a chance of becoming a gentleman. A rather smart touch in this production was to give Donna Elvira a maid who actually appears on stage and with whom Leporello strikes up a flirtation in Act One – she becomes the addressee of Don Giovanni’s “Deh vieni alla finestra” in Act Two. So when Don Giovanni reveals his wish to seduce her, we can put a face to what is normally a rather throwaway name in the text, and poor Leporello seemed genuinely irked at being thwarted by his master.

Though one of the great problems of Don Giovanni is that there is so much – musically and psychologically – to eclipse the Don at his own party. Mozart gives some of his most inward and tender music to Donna Elvira and Donna Anna, and the latter’s accompanied recitatives, sung with force and focus by Emily Birsan, were taut and keening.

Elizabeth Watts’ Donna Elvira burned with a dark, mesmerising fury: utterly purposeful, one of the few meaningful moral adjudicators in the opera, but also wounded, and vocally able to change colours on the head of a pin, particularly in her Act Two aria, “Mi tradì quell’alma ingrata”. Katie Bray’s Zerlina was sweet-voiced and secure, and was nobody’s fool: in this production the agents of the action, and the moral centre of the work, was to be found in the women of the piece, who knew what they wanted and how they felt, something reflected in purposeful and compelling singing from all three of them. There was strong singing too from the men: Benjamin Hulett’s Don Ottavio delivered his two big numbers with effortless panache, and Masetto (Gareth Brynmor John) was sufficiently burly and brutish. Miklós Sebestyén’s Commendatore plunged us into the dark with his glowering instrument.

There were some slightly shaky moments of ensemble, probably due to opening night nerves, and some fumbles with the text. But this is a production with many smart moments of direction. The closing chorus is a case in point: the characters sang from music, suggesting the moral of the story is just a performance through whose motions we’re obliged to go. Rather aptly Leporello seemed to keep forgetting the words and losing his place. And as the curtain came down, the characters couldn’t help but pour over Leporello’s book of conquests. The Don may have gone himself, but his book, and a smouldering Rodin-esque sculpture of him, defiantly remained. An unobtrusive way of encouraging the audience to reflect on why it is we go again and again to see this opera about such a corrupting, violent figure for patriarchy, and why, like Donna Elvira, we can’t quite tear ourselves away.