The Rubin Museum teams up with Buddhism to help you adjust your perspective.

Are you mad at someone? Consumed with envy? Maybe nursing a grudge? Viewing an art exhibition might provide a temporary distraction. But now a new continuing installation at the Rubin Museum of Art proposes to do something far more radical with these negative emotions: transform them into wisdom.

That is the purpose of the Mandala Lab, a 2,700-square-foot space at this downtown Manhattan museum, which specializes in Himalayan art. Open, airy and filled with an ambient glow, the lab contrasts with the Rubin’s darker galleries. As Tim McHenry, the museum’s deputy executive director and chief programmatic officer, said playfully, it is “like a lemon palate cleanser for a very dense chocolate gâteau.”

The lab, which opened on Oct. 1, is certainly sensory. In addition to creative contributions from such diverse artists as Laurie Anderson, Sanford Biggers and the musician Peter Gabriel, it offers a scent library, a breathing exercise and a sound installation involving water and gongs. During an advance tour with Mr. McHenry and the lab’s architects, Miriam Peterson and Nathan Rich, the married principals of the Brooklyn-based Peterson Rich Office, I became a subject in the lab, which is less a traditional exhibition than an interactive guide to Tibetan Buddhist thought.

“It’s almost like a series of tools for putting into practice the ideas that are everywhere in the museum,” Ms. Peterson said.

The lab’s design reflects one of those ideas. Mandalas, which are geometric diagrams of the universe — both its outer and inner worlds — serve as “visual tool kits for navigating and surviving in uncertain times,” Mr. McHenry said. A Buddhist aid to meditation and a map to enlightenment, a mandala usually has four quadrants and a circle at its center. The Rubin’s third floor already had a circular heart: the building’s spiral staircase. It was the stress of the pandemic, however, that led the museum to remodel this space, which will also host community and family programs, on a particular piece: a 17th-century Tibetan painting of the Sarvavid Vairochana Mandala.

Editors’ Picks

Enslaved to a Founding Father, She Sought Freedom in FranceThe San Francisco Homeless Crisis: What Has Gone Wrong?Three Hanukkah Desserts That Skip the Fryer

Teaching mastery over unruly emotions, “it met the needs of the time, most cogently and urgently,” Mr. McHenry said.

But whereas the painting teems with religious iconography, the clean-lined lab makes “the visual visceral,” he explained. Like the mandala’s sections, each part of the lab is associated with a klesha, or afflictive emotion; an element (earth, fire, air or water); a color; and a wisdom. The lab, however, aims to educate visitors through direct action rather than quiet study.

“Passive learning only gets you so far — you will lose it,” Mr. McHenry said, adding that this observation came from one of several neuroscientists consulting on the project. “But if you even just press a button, or better, step into the scenario itself and act it out, then that will stay with you.”

So was I ready to step in?

We began at the lab’s South Quadrant, or Journey Portal, a yellow-trimmed space whose klesha is pride. It features a large mirror and four transparent vertical cylinders, each labeled with a phrase like “I think I am better than others.” If I identified with any of the statements, I was to drop a disk (there is a huge supply) into the associated cylinder. But “I think I am worse than others” seemed like a puzzling option. How was this nagging worry prideful?

Mr. McHenry explained that feelings of inferiority were still egocentric. This quadrant’s task is to shed self-absorption and move toward the wisdom of equanimity, which embraces others as equals. (The associated element is earth — level ground.) The ability to see how previous visitors have responded is intended to enhance a sense of collective purpose.

That objective also posed a challenge for the architects. Rather than separate this three-dimensional mandala’s quadrants with walls, Ms. Peterson and Mr. Rich used lighting effects and translucent metal-mesh screens. Reminiscent of falling rain, they allow you to see fellow participants and “the next stage in the sequence,” Mr. Rich said.

Our next stop was the West Quadrant, associated with red and fire. Here, the goal is to overcome attachment: passionate desires to cling to places, things, ideas. I sat at a counter with six computer stations, each exploring a scent significant to an artist and recreated by Christophe Laudamiel, a master perfumer. The artists — Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Tenzin Tsetan Choklay, Amit Dutta and Wang YaHui, as well as Ms. Anderson and Mr. Biggers — have also made concluding two-minute videos about their olfactory choices.

At one station, I pressed a button to release the scent Mr. Biggers had selected. Was it floral — or maybe spicy? On-screen prompts asked me to examine what emotions the odor stirred in me, to read how others had responded to it and then to identify the fragrance from a series of possibilities. No spoilers here: I’ll say only that I chose incorrectly.

“There’s no wrong answer,” Mr. McHenry said, noting that the goal was to recognize the diversity of others’ reactions and then, if I chose, to augment the library by recording a scent memory of my own. (The quadrant offers blank books.) This, he said, is an exercise in the wisdom of discernment: “understanding, and perhaps even appreciation of, different people’s point of view.”

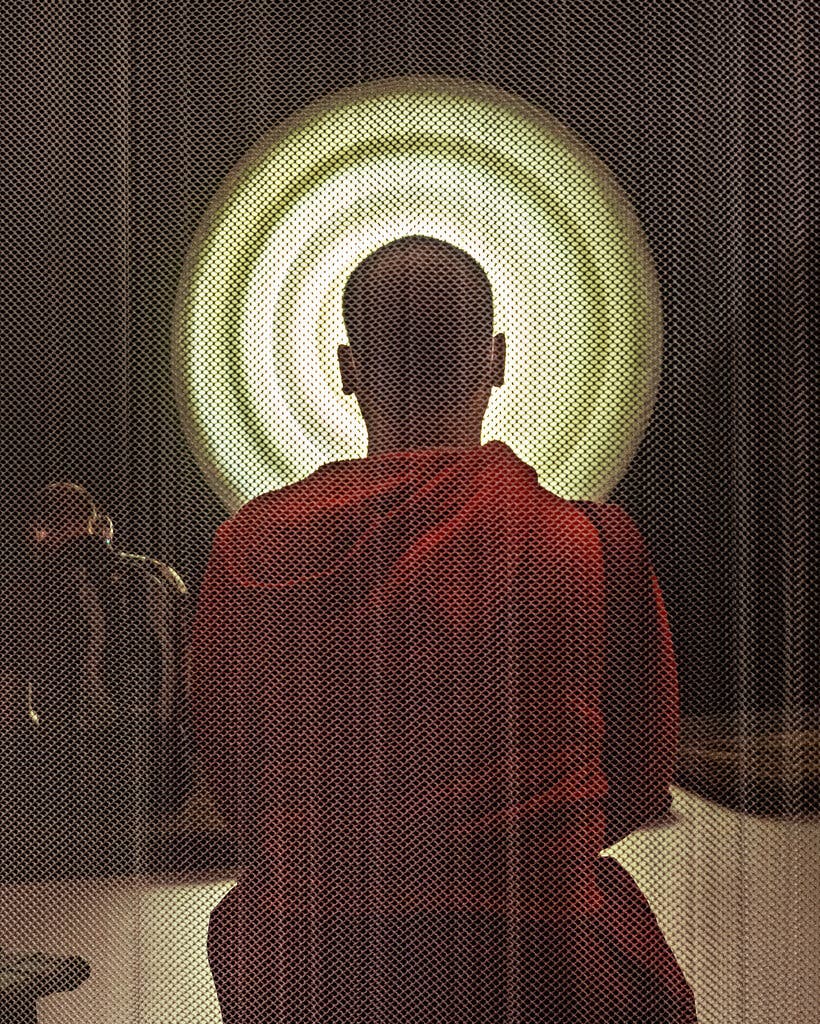

We moved on to the North Quadrant, or Breathing Alcove, dedicated to transforming envy. “You feel like you’re entering almost a hug or a protected space,” Mr. Rich said. This sense of embrace comes from a dark green semicircular back wall that displays “Untitled (Coalescence),” a large, site-specific light sculpture whose concentric discs rhythmically brighten and dim. In a phone conversation, the artist, Palden Weinreb, said he based the design on a sculpture of offering bowls he had created but wanted to “re-envision these forms in a more modern aesthetic.”

The sector’s activity is modern, too, asking visitors to achieve mind-body balance by synchronizing their breathing with the light’s waxing and waning. (The quadrant’s element is air.) According to Mr. McHenry, contemplative practices worldwide use the same pace: about five seconds of inhalation, six of exhalation. I found it remarkably soothing.

This exercise, he said, enables “a totally secular visitor to have an understanding of what it is to arrive at a sense of oneness with others.” In Buddhism, that is the wisdom of accomplishment, in which green signifies not jealousy, but growth.

A visitor participating in a breathing exercise in front of Palden Weinreb’s site-specific light installation in the North Quadrant of the Mandala Lab.Credit…Andy Zalkin for The New York Times

After that calming prelude, I addressed anger through the “Gong Orchestra” in the Eastern Quadrant, where eight of those percussion pieces hang suspended over an enormous tank of water (this sector’s element, and the source of its blue signage). The Rubin asked eight musicians to choose the gongs, which have mallets beside them.

Because you can strike a gong powerfully or gently, “it holds within it both the wrathful and the peaceful aspects of healing,” said Samer Ghadry, a drummer and sound healer who consulted on the installation and joined us there. He added, “It is like a sonic manifestation of inner awakening.”

Wandering through the orchestra — it includes a brass Korean gwangari (chosen by Bora Yoon), a large bronze gong (Mr. Gabriel), a silver nickel piece (Billy Cobham) — I was directed to imagine something that irked me. (I’ll keep it to myself, thank you.) I then struck the imposing bronze gong that Evelyn Glennie had selected. As soon as the thundering reverberation began, I pushed a pipe upward, plunging the gong into the tank. The sound transformed into a burbling rush and then ceased. But the final step was to wait until the water was still enough to reveal my reflection.

“The idea here is translating your anger, the energy of your anger, into something profoundly useful,” Mr. McHenry said, “and it’s called mirrorlike wisdom.” The exercise, conceptually poetic, felt much better than hitting a punching bag.

On the way out, the lab offers an antidote to one final klesha: ignorance. Here, touch screens enable you to select an emotion and receive a related teaching to help manage it. The Rubin also invites you to email a wisdom you have discovered.

As we approached the staircase again, I remarked that we had reached the end. Mr. McHenry gently chided me. “There’s never an end,” he said. “This is actually just the beginning.”