Perhaps one of the most important museums of American contemporary art in New York, and the whole America, the Whitney Museum of American Art, regularly organizes exhibitions of contemporary art. Among the brightest and most famous over the past year are Andy Warhol’s exhibition “From A to B and Back Again” and the exhibition of the famous photographer Kevin Bisley “A view of the landscape”. In other words, the Whitney Museum always has something to see.

Whitney Museum of American Art focuses on 20th and 21st-century American art. His permanent collection includes more than 21,000 paintings, sculptures, drawings, engravings, photographs, movies, videos, and new media artifacts by more than 3,000 artists. It focuses on exhibiting works by living artists for its collection, as well as maintaining an extensive permanent collection containing many important works from the first half of the last century. The museum’s annual and biennial exhibitions have long been the venue for younger and lesser-known artists whose work is on display there.

Whitney Museum of American Art focuses on 20th and 21st-century American art. His permanent collection includes more than 21,000 paintings, sculptures, drawings, engravings, photographs, movies, videos, and new media artifacts by more than 3,000 artists. It focuses on exhibiting works by living artists for its collection, as well as maintaining an extensive permanent collection containing many important works from the first half of the last century. The museum’s annual and biennial exhibitions have long been the venue for younger and lesser-known artists whose work is on display there.

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, the namesake, and founder of the museum was an admirer of the sculptor herself as well as a serious art collector. As a patron of the arts, she has already achieved some success as the creator of the Whitney Studio Club, an exhibition space in New York that she created in 1918 to promote works by avant-garde and unrecognized American artists. Whitney has championed the radical art of American artists at Ashcan School such as John Sloan, George Looks, and Everett Sheen, as well as others such as Edward Hopper, Stuart Davis, Charles Demuth, Charles Schieler and Max Weber.

The Whitney Library archives since 1928 show that during this time the Studio Club used the space of Wilhelmina Weber Furlong’s Art Students League gallery to exhibit roadshows with modernist works. In 1931, architect Noel L. Miller converted three houses under construction on West 8th Street to Greenwich Village – one of which was the location of the Studio Club – both the museum and the Whitney residence. Strength became the museum’s first director, and under her guidance, the museum focused on displaying works by new and contemporary American artists.

In 1961, the museum began looking for a place for a larger building. Whitney settled in 1966 in the southeast corner of Madison Avenue on 75th Street in the Upper East Side of Manhattan. The building, designed and constructed in a completely modern style by Marcel Breuer and Hamilton P. Smith in 1963-1966, differs easily from neighboring townhouses by its granite stone staircase and its external upside-down windows. In 1967, Mauricio Lasansky showed “Nazi Paintings”. The exhibition visited the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, where they appeared with performances by Louise Nevelson and Andrew White as the first exhibits installed in the new museum.

For decades the institute has been fighting against space problems. From 1973 to 1983, Whitney managed his first branch on 55 Water Street in a building owned by Harold Uris, who rented the museum for 1 dollar a year. In 1983, Philip Morris established a Whitney branch in the lobby of his Park Avenue office. In 1981, the museum opened an exhibition area in Stamford, Connecticut, which was located in Champion International Corporation. In the late 1980s, Whitney entered into agreements with Park Tower Realty, I.B.M. and The Equitable Society Assurance Society of United States, creating satellite museums with rotating exhibitions in the lobby of its buildings. Each museum had its own director, and all plans had to be approved by the Whitney Committee.

Collection

The collection begins with the painting of the Ashkan School and follows the major twentieth-century movements in America with strengths in modernism and social realism, precision, abstract expressionism, pop art, minimalism, post-minimalism, art focused on personality and politics that came to the fore in the 1980s and 1990s, and contemporary work. The museum’s signature exhibition is it’s biennial (and annual, in certain periods) review of contemporary art, which has always focused on the present, in the spirit of its founder. The main points of the collection are the final examples of their type, but the works of little-known figures also have a lot of originality. The collection includes every Wednesday; more than eighty percent are working on paper.

Whitney has had deep successes with certain key artists, covering their careers and the means in which they have worked, including Alexander Calder, Mabel Dwight, Jasper Jones, Glenn Ligon, Bryce Marden, Reginald Marsh, Agnes Martin, Georgia O’Keefe, Klaus Oldenburg, Ed Rusha, Cindy Sherman, Lorna Simpson, and David Voynarovich.

Library

Francis Mulhall Achilles Library is a research library originally built on the collections of books and works by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, founder, and Julian Sil, first director of the Whitney Museum. The library currently operates in the West Chelsea area of New York. The library in West Chelsea contains special collections and archives of the Whitney Museum. The Whitney Museum’s archives contain Institutional Archives, Research Collections, and Manuscript Collections. The library’s special collections consist of books by artists, portfolios, photographs, titles in the Whitney Style series of artists and writers (1982-2001), posters, and valuable ephemerals that are part of the Museum’s permanent collection. Records of organizational archives, photographs, curatorial scientific notes, correspondence of the artist, audio and video recordings, and documents of trustees from 1912 to the present day.

Museum today

Today, Whitney maintains close relationships with key contemporary American artists. These include Alexander Calder, Glenn Ligon, Bryce Marden, Agnes Martin, Georgia O’Keefe, Claes Oldenburg, Ed Ruska, Lorna Simpson, and David Voynarovich. And the museum’s annual and biennial exhibitions have long been a delicacy for younger and lesser-known artists whose works can be shown there.

David Hammons

David Hammons (born Springfield, Illinois, 1943) studied art in Los Angeles at the Otis Institute of Art (now Otis College of Art and Design) under the direction of Charles White, the artist welcomed him to describe African-American life. Hammons absorbed a sense of white social justice but sought radical, unorthodox materials.

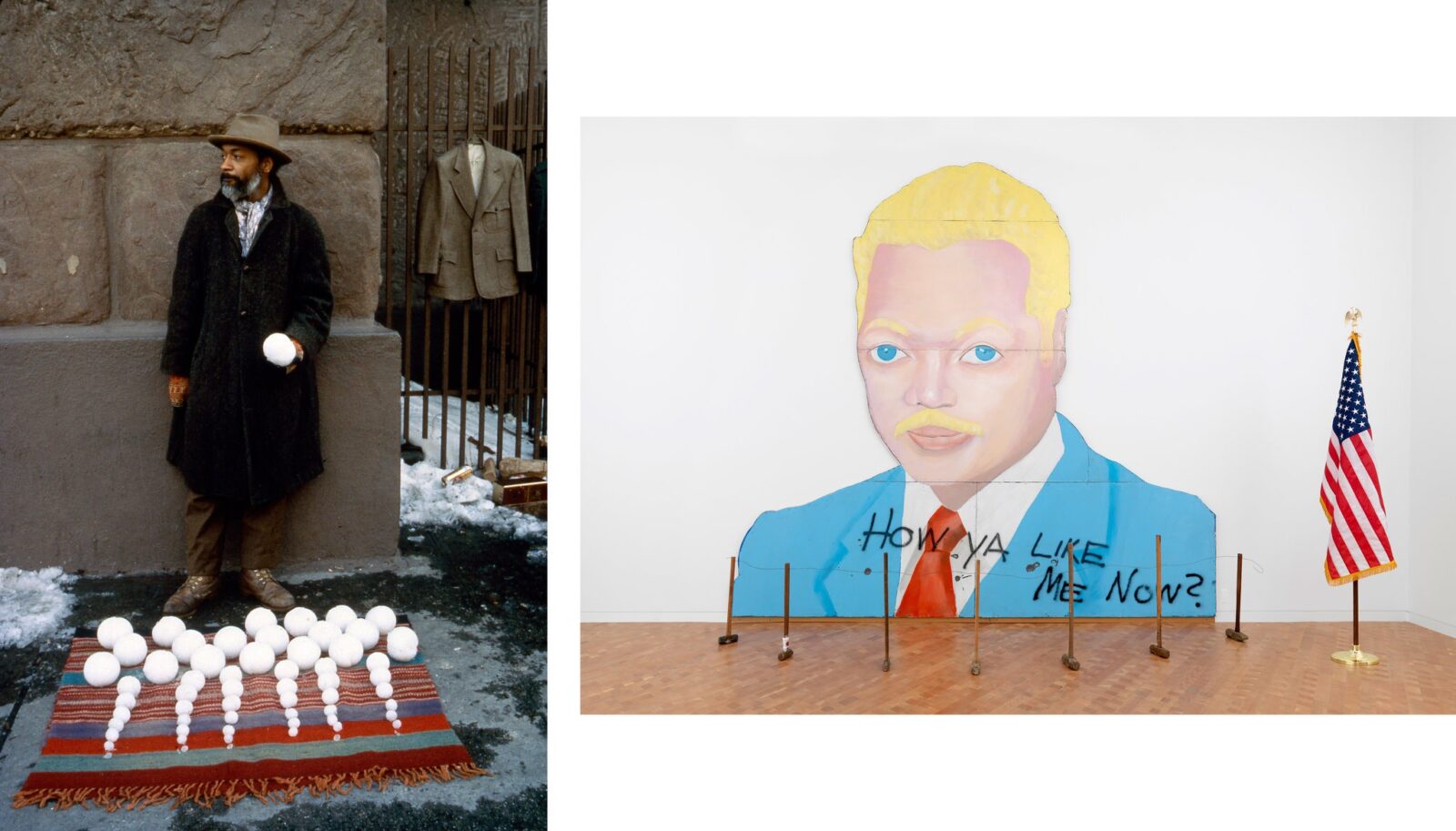

Initially, he tried to challenge the institutionalization of art, often creating ephemeral installations such as “Bliz-aard Ball Sale,” in which he sold snowballs of different sizes along with New York street vendors and homeless people to criticize notable consumption and empty notions of value. (This play continues to report on his involvement in the art world; he works without an exclusive gallery performance and rarely gives interviews). In 1988, he wrote the Reverend Jesse Jackson, an African-American civil rights activist who twice ran for president from the Democratic Party in the form of a blonde-haired blue-eyed white man. A group of young African-American men who happened to be passing by when the next year’s work was in central Washington, D.C., saw the painting as racist and smashed it with a sledgehammer. (Jackson understood the artist’s intentions.) The destruction – and the collective pain he represented – became part of the work. Now that Hammons is exhibiting the painting, he is placing a semicircle of sledgehammer around it.

“Bliz-aard Ball Sale” is a performance with photos. It is a legacy of performative ephemeral works, which begins with the Judson Dance Theater [a dance group of the 1960s, which included Robert Dunn, Yvonne Rainer, and Trisha Brown, among many others) and Happenings [a term coined by the artist Allan Kaprow to describe poorly defined works or events of performance, which often attracted an audience] the 1960s. Why it remains relevant, to some extent, because most of his work happens somehow secretly – his studio is a street. You can talk about what he does for a very long time without coming to the final answer. He does not follow a straight line and can be controversial – he does not give in to expectations.

Untitled (Night Train)

1989

Much of the work starts from the place of opposition, materially, or where it is made or done. I chose “How do you like me now? Mainly because of the ability to misunderstand the work. In a sense, it is a point of danger. The fact that a group of people took sledgehammers to him – why didn’t some people take Jackson seriously as a candidate? The mixing of boundaries between what is expected and what is not makes Hammond always relevant.

Untitled

1988

It defines why we are talking about the world of art. This work was offensive and yet we understand how to read something against its obvious presentation. It speaks about us as educated people and that is one of the reasons why we defend it. I love Hammons’ work. But I always felt very strange about this material because it did not take into account that the community could be offended. Or he doesn’t care. Who, you know, is an artist. So this is the art world talking to the art world about this work. But I am also surprised by its problematic appearance right at the moment when the public turned against public art in general and mysterious public art in particular, which usually meant the abstract. But it was worse – it was not only laughing at the public, but it was also laughing at the specific public, even if it was not his intention.

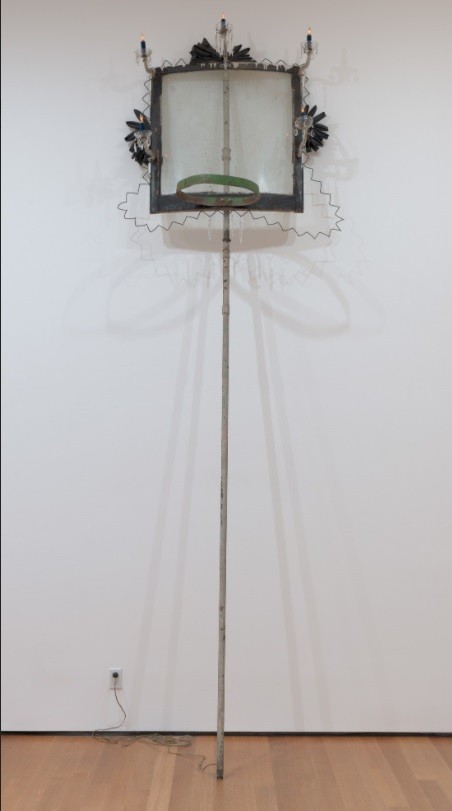

High Falutin’

1990

David Hammons, who was born in 1943 and for a long time remained the only African American to be among the most expensive American artists, is famous for his ironic works in the spirit of Banksy. Having exhibited several times in commercial galleries, Hammons usually does not deal with the system, preferring to place his works directly in the auction rooms. His crystal chandelier adorned with a basketball hoop, an ironic tribute to a community for which sport is often the only subject of interest, was recently sold by Phillips House for $8 million.

2000

crystal, brass, frosted glass, light fixtures, hardware and steel

77 x 87 x 25 in. (195.6 x 221 x 63.5 cm.)

Executed in 2000. This work is unique from a series of 3.

Estimate

$5,000,000 – 7,000,000

SOLD FOR $8,005,000

David Hammons mainly uses things from the streets of his neighborhood in his work; last year he oversaw the MoMA exhibition, which featured, in the context of “parallelism,” works by his mentor, African-American artist Charles White and works by Leonardo da Vinci. The latter is still one of the stars of the auction at the Tajan House in Paris. Leonardo’s work was discovered by specialists and experts in 2016. Tajan hopes to obtain permission from French museums to sell the masterpiece (which requires these institutions to waive their right of preferential purchase of the work classified as a national treasure) to organize the historical sale of the drawing.

Untitled

2010

African-American Flag

1990