In 1929 the Swedish artist Oskar Björk described his friend Anna Ancher in a letter to the museum director Carl Madsen like this: “I sincerely admire Anna Anker as a person and as an artist. She is like a sun glow, and in her paintings, there is something that none of us has in the same way – a quiet dedication and a palette so juicy that you savour it like a ripe fruit”.

Anna Brandum was the fifth of six children of the owners of an inn in the fishing village of Skagen. In this remote corner of Denmark, where there was no railway until 1890, she met young artists and writers at a young age who lived in a hotel. Skagen became a gathering place for progressive artists, who called themselves the “Modern Breakthrough”. The girl’s interest in drawing and painting, which she had since childhood, was encouraged by some painters, including Mikael Ancher, her future husband.

Light and color

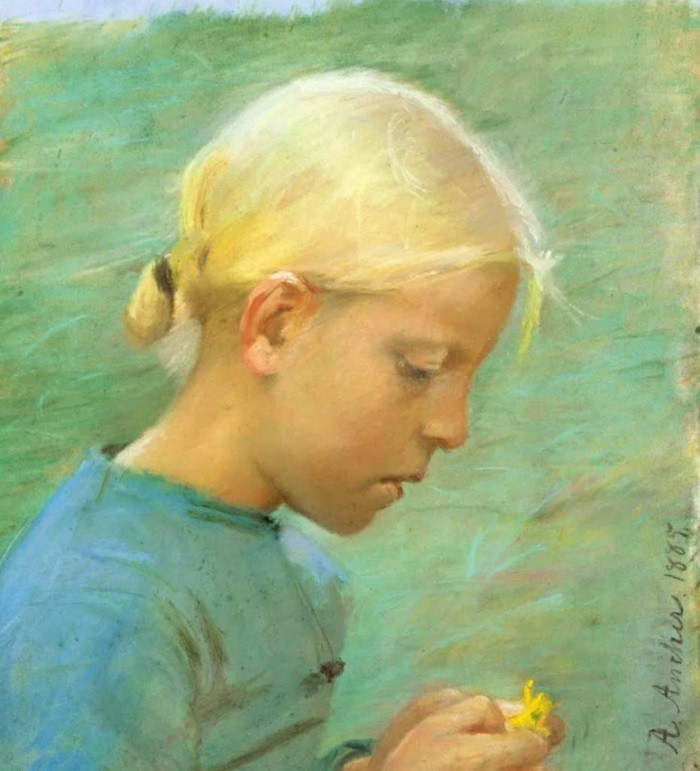

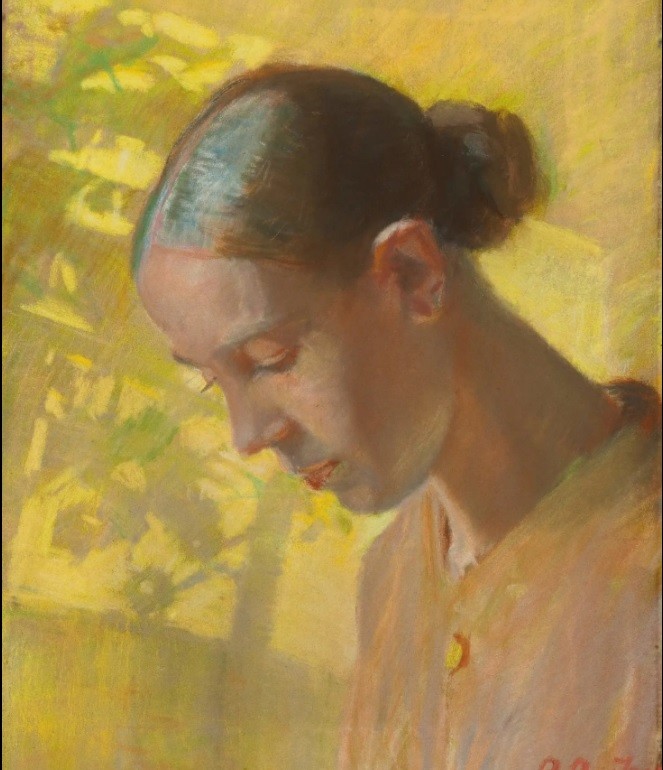

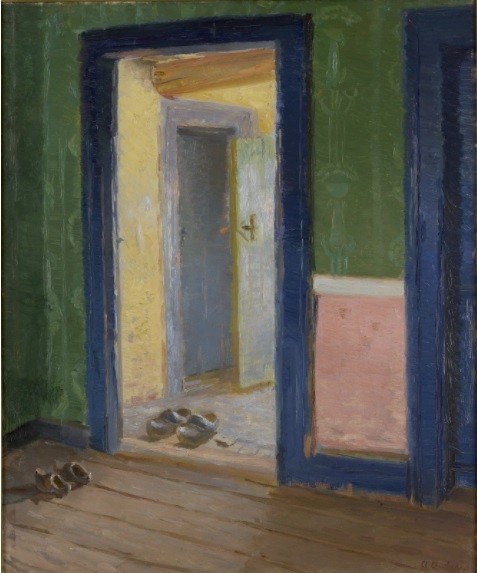

The sunlight falling on the wall is Anna Ancher’s key recurring motif. She researched it from early works in the early 1880s to the last images of rooms in the 1920s. Danish art historian Peter Larsen notes, however, that unlike the French Impressionists, Anna did not avoid real life and did not seek the elusive moment. It was written that she was the first Danish painter who managed to “catch the sunbeam”.

Working with color has distinguished Anna Ancher from other artists since the beginning of her career. She was fascinated by bright tones – yellow, pink, purple – and the choice of the palette indicates that she was not afraid to be different from her colleagues in the Skagen community.

During her travels to Paris in 1885 and 1889, and at exhibitions of French art in Copenhagen, Anna Ancher saw the latest experiments with colour. French impressionists sought to capture moments by using additional colors – yellow-purple, blue-orange, red-green – that paired to reinforce each other. Others went even further and generally began to separate colour from reality. One such artist was Paul Gauguin, whose bright paintings Anna Ancher saw in Paris and at home.

Landscape

Anna Anker is often referred to as an “interior painter”, meaning that she mainly wrote scenes indoors. However, this is a crude simplification. Landscape painting refers to much more of her work than previously thought. Her work includes a variety of landscapes – sun-drenched city scenes, the beaches of Skagen in the moonlight and images of the countryside. Many landscapes seem almost abstract, where two planes of colour meet, while others are imbued with atmosphere and full of meaning.

Simplification

Anna Ancher, like other artists in Skagen, is often associated with naturalism, a movement whose mission was to present the world as accurately as possible. But if you look closely, you will notice that it simplifies and shortens the objects depicted.

It is worth remembering that one of Anker’s teachers, Puvis de Chavannes, is known for cutting down on images, emphasizing their monumental aspects. At the same time, Europe was engrossed in interest in Japanese art. Karl Madsen, a friend of the artist, published a book on Japanese painting in 1885 and ensured that Danish painters were introduced to the special features of Japanese art, including sharply cut objects and the abandonment of perspective in the Western sense.

Adopting these principles, Anna Ancher developed her own style of painting. She often returned to the same theme, checking how much simpler the background can be, or how empty the graphic space can be. In this process, her painting moved further and further away from the true representation of the world and increasingly turned into abstract sketches on a piece of canvas.

Religion

Religious subjects in Anna Ancher’s work have long been a source of confusion. The “Modern Breakthrough” movement, to which she referred, preferred to describe the world from the scientific, objective point of view, leaving little space for religion. However, unlike other artists in Skagen, Ancher’s work has a large group of works on religious themes.

She was raised in traditional Christian values and, as known from her letters to her cousin, went to church when she studied in Copenhagen. But at the same time, she had an equal marriage and was a member of the liberal arts community.

When studying Anna Ancher’s work, it’s worth considering this duality. She may have found a place for religion in the artists’ colony. The light in her paintings has so far been described as an objective representation of the world, while religious motifs have been seen as an image of life in Skagen. But perhaps Anna Ancher’s paintings also open up space for a religious view of life.