The painter Forrest Bess (1911–77) lived most of his adult life in a ramshackle house he built on a bayou in Chinquapin, Texas, a rural stretch of the state that straddles the Gulf of Mexico. In 1956, a writer for the Houston Chronicle called it “the loneliest spot in Texas.” A bait fisherman by trade, Bess’s home was accessible only by boat, meaning that customers and visitors alike were required to drive to the end of the nearest dirt road and honk their horns until Bess could cross the water in his skiff to pick them up. The artistic legacy he left behind has for decades defied categorization and largely befuddled curators and institutions.

From one vantage point, he was the consummate Outsider artist; he was even included in the celebrated 2018 survey “Outliers and American Vanguard Art” at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. And yet, he was on the artist roster of the Betty Parsons Gallery, one of the most significant New York galleries of the 20th century, meaning he was in the same stable as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, Barnett Newman, and Agnes Martin.

He was also formally educated—he studied architecture in college, although he didn’t graduate. And we know through his many letters, which were donated to the Smithsonian Archives of American Art (and partially digitized), that he maintained deep relationships with historians, collectors, and other art-world figures, as well as with academics across the sciences, including the psychoanalyst Carl Jung.

A portrait of Forrest Bess. Photo: Courtesy Josh Pazda Hiram Butler.

“I think he never felt like he fit in, in the art world,” said Martin Clark, director of the Camden Arts Centre in London and curator of “Forrest Bess: Out of the Blue,” on view at the museum from September 30 to January 15, 2023. The show features 50 of Bess’s paintings—almost half of the just-over 100 known to still exist—as well as a collection of his letters, notebooks, and other ephemera. “He chose to position himself on the margins in different ways, but if you read his letters, they’re very knowing.”

In those letters, Bess described his younger self as “a clumsy awkward kid who was always on the outside looking in. But the key thing was that he was a gay man in Texas,” Clark said. “And though he came out to certain friends and to people he felt close to—and he actually wrote very movingly about his sexuality—he never found his place within that either.”

Bess wrestled to square his queerness with a life that he saw as otherwise conventionally masculine. This culminated in two surgeries he performed on himself in an attempt to become what he called a “pseudo-hermaphrodite.” Bess wrote that he believed these surgeries might bring him immortality, though whether his words were intended to be taken literally or figuratively is a matter of debate. He also likely hoped they would bring an end to the internal disharmonry that had dogged him for so many decades.

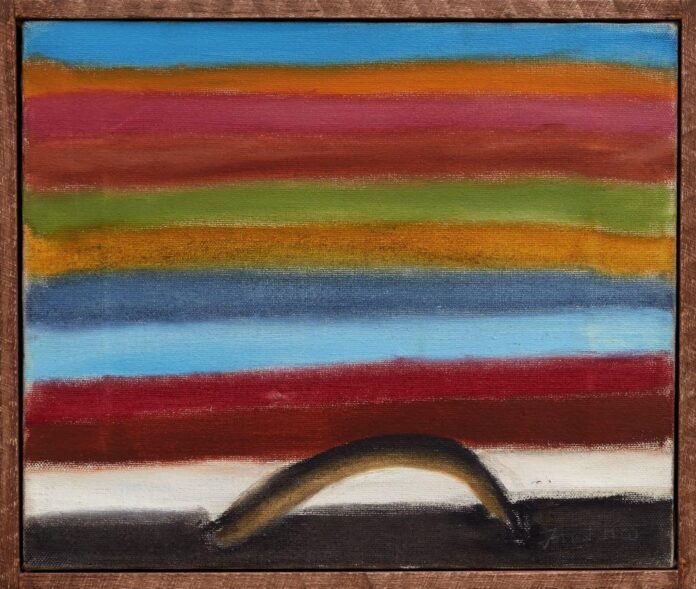

Forrest Bess, (1970), oil on canvas. © documenta und Museum Fridericianum gGmbH Photo: Andrea Rossetti.

“There are, in my makeup, two distinct personalities,” Bess once wrote. “Number one is the military engineer, the oil-field roughneck, the accomplisher of missions well-done. Number two is weak as a jellyfish, he suffers much, thinks deeply, and is quite passive in nature. Number one was reality, the oilfields, mud tents, struggle. The other, the child who hid in the sandbanks and spent the day watching clouds and gathering flowers.”

The surgical procedures were based on an Aboriginal Australian tradition that Bess studied, and his desire to merge what he felt to be dissonant aspects of himself was a hyper-literal take on Jung’s theory of individuation, of which there is no doubt that Bess was familiar.

He kept a scrapbook—most of which is now presumed to be lost—that he referred to as his Thesis, in which he wrote extensive notes and collected medical texts and other forms of historical research that aligned with this idea of reaching an enlightened state through gender non-dualism, or by merging the male and female aspects of oneself. (Pages from the Thesis are on view at the Camden Arts Centre.)

Forrest Bess, (1946/47), oil on canvas. © documenta und Museum Fridericianum gGmbH. Photo: Andrea Rossetti.

He wrote multiple letters to Parsons in 1958 asking if he could exhibit the Thesis alongside his paintings in a show at the gallery, but Parsons rejected the idea, saying she “would rather keep it purely on the aesthetic plain.” A 2011 exhibition of Bess’s work, curated by the sculptor Robert Gober and displayed as a show-within-a-show at the 2012 Whitney Biennial, attempted to rectify this, presenting some remaining Thesis pages in a vitrine alongside 11 paintings.

Bess saw the Thesis “as absolutely underpinning all of the work he was doing,” Clark said. And just as notions of union and non-duality are at the core of nearly every major religious and mystical tradition, the Thesis too centers on “the idea of opposites coming together to produce a kind of transcendent state,” the curator added.

When World War II arrived, Bess enlisted in the military, where he was tasked with designing camouflage. He served from 1941 to 1945, but after suffering a nervous breakdown, as well as being brutally beaten with a lead pipe by fellow soldiers who suspected him of being gay, he met with a military psychiatrist. Bess spoke in their meeting about “visions” he’d had with regularity since childhood, in which abstract symbols would appear to him, and the psychiatrist encouraged him to paint them. In 1946, Bess discovered Jung’s psychological theories, which renewed his focus on these forms.

“I never knew there was a clue to the understanding of my symbols until I ran across Jung accidentally,” he wrote in a 1952 letter to collector Dominique de Menil. “Not only have I found meaning in my work, but I have been given another dimension.” Bess described the symbols as “the language of the unconscious” which “contains some ancient sorcery.” He exchanged letters with Jung as well, even mailing the renowned psychiatrist a painting.

Forrest Bess, (1959), oil on canvas. © documenta und Museum Fridericianum gGmbH. Photo: Andrea Rossetti.

And unlike many other members of the Parsons gallery roster, Bess did not view himself as an action painter or an Abstract Expressionist. His work was not concerned with improvisation, but was rather an attempt to translate and explore the visual lexicon that came to him in these meditative states.

“I just go to bed, close my eyes and see these things. I keep a notebook handy and sketch them down in the dark or turn on a flashlight and sketch them,” he wrote of his process in an undated letter to art historian Meyer Schapiro, who was a close friend to Bess. “I get up the next morning—spend the day fishing, then that night I paint the canvas as it was seen. In fact I sense that I have very little to do with what is put down on the canvas.”

The surfaces of Bess’s paintings are rich and thick, the paint often applied with the use of a palette knife, the biomorphic forms of his symbology floating amid intricate textures and patterns. He often framed the work himself using driftwood.

Forrest Bess, (1952), oil on canvas. Collection of Beth Rudin DeWoody Photo: Robert Glowacki. Courtesy Modern Art, London.

“They have an object-quality, like a relic or something devotional,” Clark said. “He was very close to the natural world that he was part of, so I think those textures and that sense of a tangible, physical world was important to him, and it comes through in the painting.”

Despite having six solo shows with Betty Parsons in his lifetime, Bess never found commercial success. He spent his life in poverty, and the lack of recognition from the art market and institutional world continued for years after his death. “Modernism, for such a long time, was about being secular, it was about purity, internationalism; it was definitely not about the esoteric or the occult or any of these messy things,” Clark said. “The work wasn’t commercially successful and he just fell through every sort of crack.”

“Now, I think Bess speaks to the messiness which has become much more a part of the way that artists do operate,” Clark said. “We’re much more accommodating of artists moving through and across ideas. There’s much more interest in what would be considered non-normative or queer systems of thought.”

Today, it is easier to understand Bess’s search to feel complete, the curator added. “The tragedy is that, at the time he was doing this, there wasn’t really a way to work as an artist like that.”