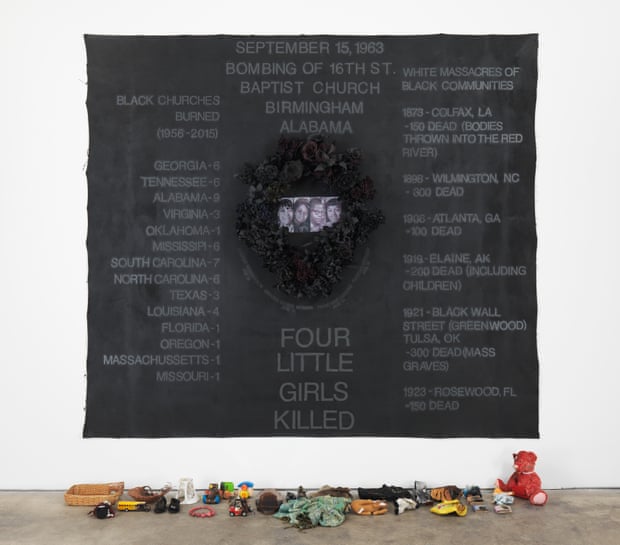

Four Little Girls by Howardena Pindell is a tribute to the young victims of the church bombing in 1963. Then, these girls were killed by white supremacists. This is just one of many violent stories told through American art in a new exhibition dedicated to violence against black people.

The art exhibition is called “Places of Struggle: American Art Against Anti-Black Violence. ” Its curator wants to correct the misconception that anti-black violence is something new.

Artists have been dealing with this issue of anti-black violence ever since it has been a problem in the United States. I think that American art has a unique ability to make us stop and think about things that we might not be open to in a different context, says Janet Dease.

So the organizers want to draw a line connecting the history of the subject. Lisa Corrin, director of the Northwestern Block Art Museum, said this art exhibition would have been as relevant in 1992 as it was in 1962 as it was in 1922.

Contemporary acts of violence, such as the killing of George Floyd, are all too fresh in the country’s memory. But works like Norman Lewis’s 1943 watercolor “Untitled” (“Police Beating”) show visitors that the problem is not new.

Dees says there are a couple of pieces in the exhibition that look like they were made yesterday. The art exhibition features about 65 works in a wide variety of media from US collections. The art exhibition examines the artworks over about 100 years, from the anti-lynching campaigns of the 1890s to the founding of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Dees has been studying anti-black violence and art for over a decade. It took six years for the Place of Struggle: American Art Against Anti-Black Violence art exhibition to come together. The art exhibition has three sections. Each of the sections focuses on different strategies that artists use to explore different subjects of anti-black violence.

One area focuses on abstraction and the artists avoid the literal representation of violence, the second is more figurative, and the third uses the literal representation of violence. Dees says there is a lot of material that could be included in the exhibition, but it was important that a moderate amount of work was presented, so that it supported the thesis of the art exhibition, but was not unnecessarily burdensome for visitors.

The collaborative video cover, created by the Pope twins, Carl and Karen, was included by Dees due to the deep impression she had on her after she saw it at the 2000 Whitney Biennale. After not being seen in public for years, “Palimpsest” shows Karl Pope’s body being branded, cut, and tattooed while his sister recites a poem.

Karl Pope used his body as a writing surface and Karen Pope’s poetry to explore slavery and the scars left on black bodies. “There were a lot of discussions between the two of us and I cheered him on and I didn’t quite understand what he wanted to do, but I just felt that he was doing something important, and that’s all I needed to know,” says Karen.

Using my body as a writing surface and having Karen speak with emotion, as she did, about her own experience in her own body as a black person, it makes all of these things really hard for people to even understand why I would do this, Carl says.

Knowing that many visitors can be influenced by the graphic nature of the art exhibition, the designers have deliberately included quiet spaces for reflection, as well as a research center for those who want to explore the topic more or even connect with civil rights activists.

The exhibition will then travel to the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts in Alabama.