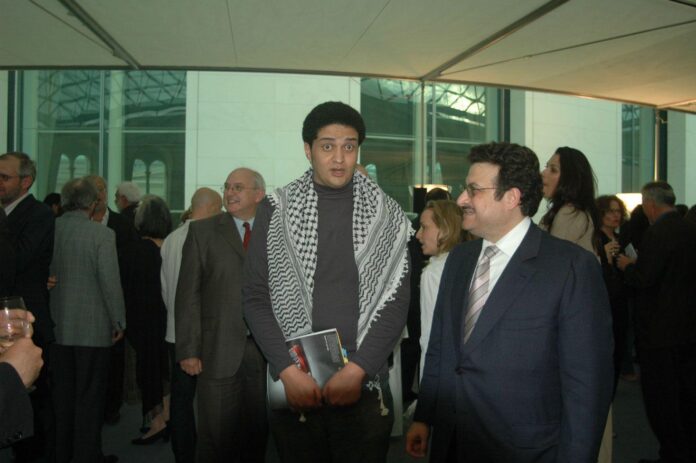

The poet, artist and curator, Ashraf Fayadh, of Palestinian origin but born in Saudi Arabia, was released from a Saudi prison on the evening of the 22 August after eight years and eight months, in the course of which he was given 800 lashes. For nearly three months, in 2015-16, he lived under sentence of death. His case aroused profound disquiet within Saudi Arabia, where he co-founded the influential Shattah artists collective in Abha in 2003, and outrage abroad, where Fayadh had been involved with some of the earliest exhibitions of Saudi contemporary art outside of the Kingdom, including Rhizoma: Generation in Waiting, which he co-curated at the 2013 Venice Biennale.

According to sources, the eight-month delay in his release was due to the bureaucratic difficulty of releasing a Palestinian refugee back into Saudi society. It is understood that the Riyadh office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, foreign diplomats, US academics as well as more sympathetic authorities in Saudi Arabia, finally secured Fayadh’s release, which was announced on Facebook from Ramallah by Murad Sudani, the head of the Palestinian Writers Union.

His ordeal began in August 2013, when he was arrested by the religious police after a man reported that in 2011, he had made blasphemous remarks in a café in Abha, a city in southern Saudi Arabia. The accuser also alleged that Fayadh passed around a book he had written that promoted atheism and unbelief. The police held him for a day, then released him, but he was re-arrested on 1 January 2014 and charged with a long list of offences that included denying the day of resurrection, “objecting to fate” and “divine decree” and “having an illicit relationship with women and storing their pictures in his phone”. In reality, the photographs were merely of Fayadh next to a woman in modest dress, taken at the opening of an exhibition in Jeddah.

Ashraf Fayadh’s Together against Recycling People, from the series Palestinian ID, made for the first Shattah exhibition in Abha in 2003

His friends say the real reason for his persecution is that the religious police saw him as an easy target, a marginalised artist and a Palestinian, whose disappearance, they thought, would not arouse attention. What is certainly true is that artists have to tread a fine line in Saudi Arabia, where any questioning of religious or temporal authority poses a risk and has to be veiled in metaphors and symbolism.

At the trial, which took place between February and May 2014, Fayadh denied the charges and called three witnesses challenging the testimony of his accuser. The defence witnesses said that the man had denounced Fayadh following a personal dispute and that they had never heard blasphemous statements from Fayadh. His book, Instructions Within, published in Beirut 2008, consists of love poems that do not insult the Prophet nor break any social rules, but contain his philosophical reflections on life.

On the last day of the proceedings, Fayadh said, “I am repentant to God most high and I am innocent of what has been said about my book in this case”. But on 26 May 2014, the general court of Abha found Fayadh guilty and sentenced him to four years in prison and 800 lashes. It rejected the prosecution’s request for the death sentence for apostasy due to trial testimony indicating “hostility” between Fayadh and the man who reported him, as well as Fayadh’s repentance. The prosecutor appealed the ruling and the case was sent back to the lower court, where, on 17 November 2015, a new judge reversed the previous judgment and sentenced Fayadh to death for apostasy. A week later, Ashraf Fayadh’s father died of a stroke and Fayadh was not allowed to attend his funeral, but he wrote a poem, of which this is a quotation:

I saw my father for the last time through thick glass

then he departed, for good.

Because of me, let’s say.

Let us say because he could not bear the thought

I’d die before him.

My father died and left death to besiege me

without it frightening me sufficiently.

Why does death scare us to death?

The Saudi art world was deeply disturbed by the treatment of a well-known colleague by the religious courts and Ashraf’s case was taken up by the Saudi human rights lawyer Abdulrahman Al-Lahem, who said that the arguments against Fayadh were deeply flawed, invalid under Shariah law, and did not take account of medical evidence of Fayadh’s unstable mental state.

Outside the Kingdom, there was an emergency reaction from the world of art and letters. Protests were made by more than 60 international organisations, including Pen International and America, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty Internationaland Freedom House, while a petition was signed by around 100 Arab writers.

Stephen Stapleton and Ahmed Mater, the co-founders of the Saudi-British art group Edge of Arabia to which Fayadh belonged, Aarnout Helb, founder of the Greenbox Museum of Saudi Contemporary Art, and The Art Newspaper organised a private petition to the king that was translated into Arabic and delivered by a senior US diplomat to the Diwan (royal court). The letter said, “If justice fails Ashraf Fayadh, he not only loses his life, but a whole generation of creative, useful citizens, the ones who can contribute to the happiness and prosperity of your country, will be wounded and discouraged.”

The letter came from the directors of the British Museum, the Tate and Tate Modern, the president and exhibitions secretary of the Royal Academy of Arts, the master of St Cross College, Oxford; from the directors ofthe Musée Guimet and Centre Pompidou in Paris; the director of the Museum für Islamische Kunst in Berlin; the directors of the Stedelijk, Van Gogh and World Cultures museums in the Netherlands; the directors of the Museum of Modern Art and Brooklyn Museum in New York, and of the Los Angeles County Museum.Karen Armstrong, the ecumenical writer and author of Mohammed: a Biography of the Prophet, which is a best-seller in the Islamic world, added her support to the petition, while a clear, medical description of the agitation often manifested by someone with Fayadh’s condition was written over Christmas for his defence by Edward Bullmore, head of psychiatry at Cambridge University.

In January 2016, when the appeal was due to be heard, hundreds of writers in 44 countries took part in readings of Fayadh’s poetry and a letter signed by Nobel laureates Orhan Pamuk and Mario Vargas Llosa was sent to the US president, UK prime minister and the German foreign ministry, asking them to put pressure on the Saudi government. The verdict on 1 Feb 2016 was both a relief and disappointment. The death sentence was quashed but Fayadh was sentenced to eight years with 800 lashes, to be delivered over 16 sessions.

Now, after much interceding on his behalf behind the scenes, Ashraf Fayadh is finally free, apparently in good health, both physical and mental, and is being supported by friends and family in Saudi Arabia. His release coincides with the diminishing power of the ultra-conservative religious authorities under new leadership in the Kingdom. Fayadh was originally sentenced by a theocratic judicial system that aimed to hinder, even dismantle, the Saudi art movement of which he was a key part. His friend, the artist Ahmed Mater, told the French news channel RFI in July that what happened to Fayadh belonged to a less open time and would be unlikely to be repeated today.