Briefs have been filed in anticipation of oral arguments at the US Supreme Court on 12 October over the rules that determine whether a secondary work of art has transformed a prior one enough to avoid liability for infringement.

The key question is whether a change in the first work’s “meaning or message” can be a factor. The dispute springs from the 2021 rejection by the Second Circuit federal appeals court of a claim by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (AWF) that a series of works by Warhol, which he based on a copyrighted, licensed photograph by photographer Lynn Goldsmith, were a permitted “fair use”. The Second Circuit said Warhol’s works failed all four of the required fair use tests under US copyright law, including the “purpose and character” or “transformativeness” test, which examines whether the second work adequately changed the first.

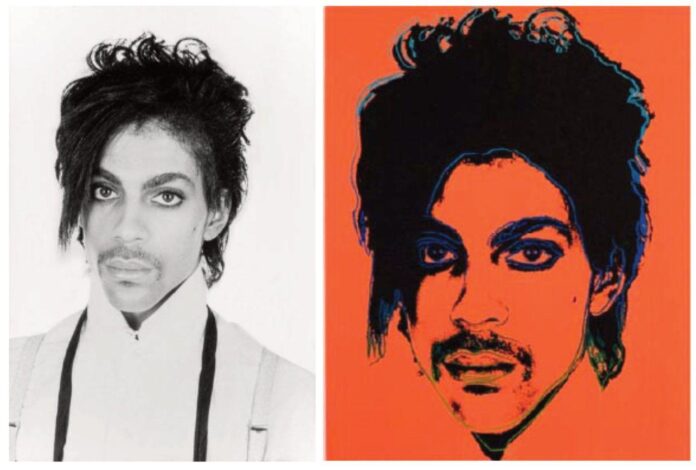

The Second Circuit opinion said the Warhol works recognisably derived from, and retained, the essential elements of Goldsmith’s portrait, but that transformation must comprise “more than the imposition of another artist’s style”. Whether a work is transformative cannot turn “merely” on the artist’s “stated or perceived intent” or “the meaning or impression” that a critic or a judge draws from it, the court said—otherwise, “any alteration” could be recognised as transformative under the law.

U got the look

In 1984 Vanity Fair magazine paid Goldsmith $400 for a license to use her 1981 portrait of the musician Prince as an artist reference for an illustration for its November issue, but “no other usage”. The magazine hired Warhol for the job, and the issue credited Goldsmith twice. Later, Goldsmith discovered that Warhol had created 15 additional works based on her photograph, and that, Warhol having died, AWF had licensed one of them in 2016 to Vanity Fair’s parent company, Condé Nast, for $10,250—a fee she says should have been paid to her.

After Goldsmith asked AWF to “amicably resolve” the matter, the foundation sued in the federal district court for a ruling that the works Warhol created, known as the Prince series, were a protected fair use. In 2021 the Second Circuit turned down AWF’s request, and further rejected its argument that fair use was supported under a 2021 Supreme Court decision involving software code copying by Google.

AWF is now asking the Supreme Court to overturn the Second Circuit opinion as incorrectly forbidding courts from considering the “meaning or message” of the works at issue in fair use cases, which it says courts are instructed to do under precedent from the Supreme Court and other federal courts. The Prince series undisputedly changes Goldsmith’s meaning, AWF says, citing Goldsmith’s testimony that her image portrayed Prince as uncomfortable and vulnerable, while the district court concluded Warhol had transformed her photo into an “iconic, larger-than-life figure”, removing the “humanity” in Goldsmith’s portrait.

The Second Circuit also overly relied on a visual similarity test, AWF says. It adds that, if the decision is allowed to stand, it would chill creative speech and deny fair use protection to works of appropriation art that borrow from other works. It could also follow that museums and galleries concerned about whether their works are protected under copyright law could choose not to display them.

Goldsmith says the issue is narrower. She points to the fourth fair use test, which asks how the secondary use affects the original work’s potential market, and cites the licensing dollars creators will lose to copiers if AWF’s “meaning or message” test prevails. AWF’s licensing of one of the Prince seriesworks to Condé Nast displaced her ability to license her own portrait to the magazine, she says. She adds that AWF’s “meaning or message” test is “manipulable” and would “inject instability into multi-billion-dollar licensing markets” across different kinds of creative work, because “artists, critics, and the public often disagree about what art signifies”, and perceptions can change with time. She adds that AWF’s warnings of “the death of art” if there is no meaning or message test are exaggerated, because a fair use analysis includes four factors, and AWF lost on all four.

Sign ’o the times

The case has attracted widespread attention among copyright watchers, with numerous friend of the court briefs filed with support for both sides. Simon J. Frankel, a copyright lawyer in San Francisco, who filed an amicus brief on behalf of nine large US art museums and the Association of Art Museum Directors that supported neither party, told The Art Newspaper, “The Second Circuit’s decision did not address museums’ display of Warhol’s original works or their publication of reproductions, saying such uses are ‘not particularly relevant’. This left uncertain whether museums or collectors may be potentially liable for copyright infringement for displaying or publishing Warhol’s works as part of their mission. A decision from the Supreme Court should make clear such museum uses would be permissible.”