Barbara Kruger is in the news. The feminist artist who came to prominence in the 1980s is having a major moment at the Venice Biennale, with her site specific work Untitled (Beginning/Middle/End) making a statement in the central exhibition at the Arsenale. Meanwhile, in New York. a large-scale commission for the atrium of the Museum of Modern Art is in place through January 2022 and a series of recent works is on view across David Zwirner’s three West 19th Street spaces.

Since the 1970s, Kruger has developed a distinctive visual language by overlaying poignant textual slogans atop black-and-white photographs and found imagery from magazines and textbooks. The juxtapositions often point out the absurdity or injustice of the power dynamics that define contemporary society and often go unspoken. Many of her most famous works were made in the 1980s—but, as evidenced by her recent turn on the cover of , current events have made them feel more vital than ever.

So what does this new relevance foretell about her market? We took to Artnet’s Price Database to investigate.

The Context

Auction Record: $1.2 million, achieved at Christie’s New York in November 2021

Kruger’s Performance in 2021

Lots sold: 36

Bought in: 9

Sell-through rate: 80 percent

Average sale price: $72,973

Mean estimate: $42,458

Total sales: $2.6 million

Top photograph price: $1.2 million

Lowest photograph price: $11,970

Lowest overall price: $544, for a flag screenprint in colors printed on cotton.

© 2022 Artnet Worldwide Corporation.

The Appraisal

- I Shop Therefore I Am. While she has been working steadily since the 1970s and has had no dearth of critical attention, Kruger’s auction market didn’t really take off until the early 2000s. In November 2004, her now-iconic 1983 work, I Shop Therefore I, sold for a record $601,600 at Phillips de Pury & Company in New York.

- Public vs. Private. Kruger’s most sought-after works are her classic, domestically scaled, photographic works in red frames and works on large tarps from the late 1970s through the 1980s. Many of these works are already in institutional collections, and those held by private collectors rarely change hands. When they do, it is most often on the private market, where they can trade well into the seven figures. Due to the constrained supply at auction of iconic works, just 10 lots have surpassed the $500,000 mark since 2004. Works regularly trade on the primary and secondary private markets for much more. David Zwirner, which added Kruger to its roster in 2019, sold Untitled (Striped 2) (2019) for $600,000 at Art Basel Miami Beach in 2021, and longtime gallery Sprüth Magers has reported higher prices for her older works from the 1980s, selling Untitled (Your devotion has the look of a lunatic sport) (1982) for $750,000 at Art Basel’s Swiss edition in 2021.

- Trending Upwards. Kruger’s best year in terms of total sales at auction was 2019, when her work generated $3.3 million, buoyed by three prices in excess of $500,000 and a 43 percent uptick in supply year over year. Following a slight pandemic dip, 2021 was another exceptional year, with the greatest number of lots to date (45) offered at auction. Kruger’s existing record was achieved during that year’s fall sales in New York.

- Market Opportunity. There are not a lot of underserved areas of Kruger’s market. Her output has been consistent but highly edited, so relatively lean. While there are fewer people who can collect the large-scale, non-residential pieces, like her big video installations, there is still demand for them and they are highly sought-after by institutions. If one is looking for some rare opportunity to buy, there are occasional examples of her maquettes on the secondary market for prices in the $60,000 to $80,000 range.

- Barbara Kruger Was Right. As her work gains in popularity, the upward trend looks set to continue. So far in 2022, she has already achieved more in total sales than in the whole of 2020, and 1,936 users have searched Artnet’s Price Database for information about the artist in the past 12 months.

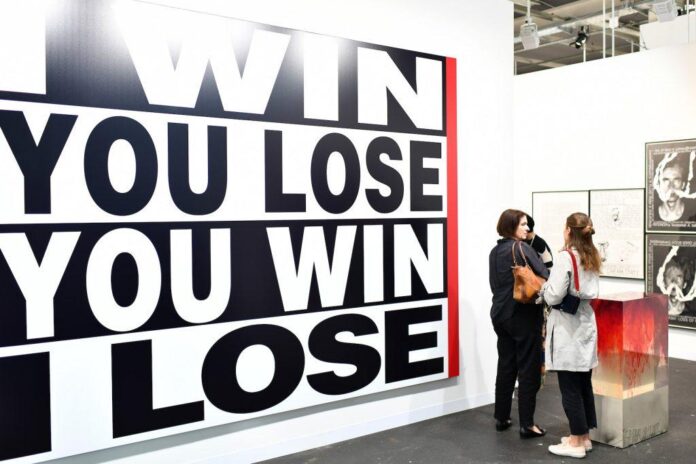

Barbara Kruger, (2022). Photo by Ben Davis.

Bottom Line

Kruger’s distinctive visual vernacular has permeated the public consciousness—outside the art market, her work has entered the homes (and Instagram feeds) of many through mass reproductions. At the same time, her aesthetic has unironically been absorbed by streetwear brand Supreme and other corporations. Kruger’s anti-hierarchical stance means she has not resisted these imitations—and does not see their existence as diluting the power of her own work.

There was a period in which the cohort of collectors for Kruger’s work was relatively small, but the audience has expanded in recent years. Throughout her career, there has been no shortage of curatorial, institutional, and critical support of her work, and demand from museums remains strong.

Her poignant social commentary and vital feminist works from the 1980s are enjoying new relevance in an increasingly oppressive political and social environment. As Kruger told the earlier this year, “It would be kind of good if my work became archaic.” Alas, not yet: Last year’s record was set for the 1981 work, Untitled (Your Manias Become Science), which feels increasingly relevant in an age of climate change denial and pandemic conspiracy theories.

The progression of Kruger’s market can also be understood in the context of broader attention being paid to a group of important women photographers and graphic artists primarily working with female gallerists—think Mary Boone, Metro Pictures, and Sprüth Magers. While Cindy Sherman’s market took off more quickly than the others, we are now seeing work by the likes of Louise Lawler and Sherrie Levine gaining traction, too—and Kruger is at the center of it all.