An exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art examining Edward Hopper’s enduring fascination with New York has revived a decades-old dispute about how a church minister came to own hundreds of works by the American artist.

The show, Edward Hopper’s New York (until 5 March 2023), draws extensively on the artist’s personal items such as letters, photographs and journals from the archive donated to the museum by the reverend Arthayer R. Sanborn. Sanborn’s Hopper collection has long been known about but has been off limits for close to 50 years.

What is less widely known is that Sanborn provided first-hand testimony of how he came to discover this “treasure trove” of Hopper papers, ephemera and art in the attic of Hopper’s childhood home, which then controversially came into his possession. The attic contents are only a small proportion of Sanborn’s eventual collection—he later acquired the contents of Hopper’s Washington Square studio.

Sanborn, who died in 2007, was a Baptist minister in Hopper’s birthplace of Nyack, New York, and lived near the Hopper family home. He had helped Edward’s sister, Marion as caretaker of the Nyack property, where she continued to live, and had assisted Edward and his wife Josephine in the last years of their lives. Before their deaths, Sanborn discovered the “trove”, which included family documents but also early works, in the home’s attic. He ultimately came to own more than 300 Hopper artworks, the New York Times reported. Yet Hopper’s artworks had been explicitly left to the Whitney in 1968 in Josephine Nivison Hopper’s will.

Edward Hopper, around 1937

© Harris & Ewing

Key to the mystery?

The reverend related the circumstances leading up to his astonishing legacy in a lecture given at the Historical Society of Rockland County in New City, New York on 22 July 1982, to mark the 100th anniversary of Hopper’s birth. It all began when he became a regular visitor to the Hopper family home. “The only reason I went into the attic was… I had a key,” he said, “I could go in and out at my choice.” He added that the reason he had a key was that he’d bought Marion [Hopper’s sister] a television “just to get her off my back, to loosen her, to sweeten her up a little bit”. And then Marion had got “so engrossed in these soap operas” that she couldn’t get to the phone, to the door—hence the necessity of the key.

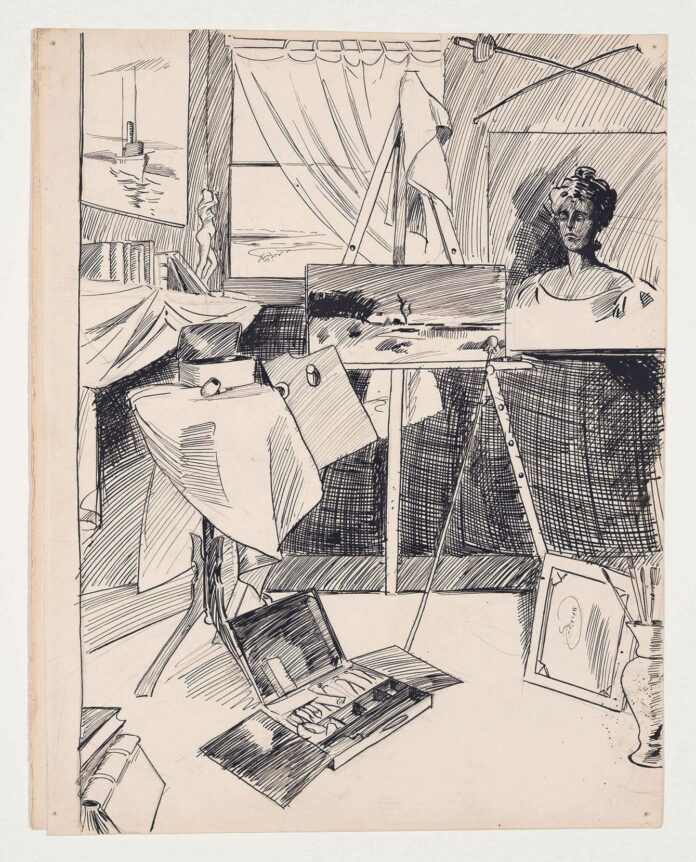

So Sanborn took care of the Hopper property and one day he and his son went up to the attic to deal with a dead bird. They began looking around and made a discovery. “It was a treasure trove, unimaginable!” he told the audience. The Hoppers “saved everything”, and this was also Hopper’s first studio. He showed the audience Hopper’s early drawing of this studio, which included a picture on an easel. “I have this easel,” he said. “I have the picture that’s on there that he painted.”

As the New York Times reported in 2020, the painting was revealed by a PhD student to be the young Hopper’s version of a painting by the American tonalist Bruce Crane, copied from a Victorian magazine for amateur artists. It was mislabelled by Sanborn as a painting of the artist’s local ice pond in Nyack, and later sold through Heather James Fine Art.

Other more notable paintings that Sanborn came to own include City Roofs (1932), a golden-hour scene of rooftops included in the Whitney exhibition.

How Sanborn, who in the early 1970s began selling some of the Hoppers, acquired these has been the subject of controversy long before the show opened on 19 October. He had said that some were given to him as gifts from the family, and others he had acquired when he purchased the contents of the Nyack house and Hopper’s New York apartment. But the New York Times investigation, which included a recent review of several internal records from the Whitney, did not find a clear provenance for his collection.

Edward Hopper’s City Roofs (1932)

©️ 2022 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper/Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS)

City Roofs, for instance, had once hung in Sanborn’s dining room, and, according to his son, was a gift from the Hoppers. But Josephine Nivison Hopper, who kept track of works in a ledger, had last labelled it as “here in studio”, according to the Hopper scholar Gail Levin, who authored the artist’s catalogue raisonné.

Another study, for the painting Sunlight in a Cafeteria (1958), is listed in an exhibition catalogue as acquired by Sanborn from the estate of Josephine Nivison Hopper; in a letter to its later owner, Yale University, Sanborn wrote that he received the drawing before her death, as a gift.

Sanborn owned a study for Hopper’s Sunlight in a Cafeteria (1958), above, which he said was a gift. Sanborn’s son said City Roofs (1932), above, was also a gift from the Hoppers

©️ 2022 Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper/Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS)

Levin, a professor at Baruch College, New York, who also worked as the Whitney’s Hopper curator between 1976 and 1984, has been Sanborn’s loudest critic. She alleges that the late minister was a thief who sold Hoppers that were never rightfully his, to buyers including institutions such as the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Her website has drawn attention to Sanborn’s Rockland lecture on the attic discovery, which is available on the Soundcloud streaming platform.

She has also argued that the Whitney, to whom Josephine Nivison Hopper bequeathed all of her husband’s art, failed to defend the public interest because it allegedly did not attempt to recover the works in Sanborn’s possession. For Levin, that loss was compounded by the added injury of lack of scholarly access to this critical Hopper material over decades.

“The museum is aware of claims made by a former curator,” the Whitney said in a statement to the New York Times. “Those claims were considered when first made and were again researched more recently. The museum has found no basis to pursue the matter, and is satisfied with what it received.”

The Whitney received its gift of Hopper memorabilia from Sanborn in 2017 through the Arthayer R. Sanborn Hopper Collection Trust. It told the New York Times that it had been negotiating for the collection, now known as the Sanborn Hopper Archive, for more than two decades. It is unclear, according to the newspaper’s investigation, how works that were stored in the attic in the Hopper house were inventoried by the Whitney; the museum reportedly gave that duty to the Bank of New York, the executor of Josephine Hopper’s will.

• Listen to an interview with the curator Gail Levin on The Week in Art podcast