More than 340 people, including artists Ali Cherri and Michael Rakowitz, have signed an open letter supporting Iraqi artists who objected to their works being shown at the Berlin biennale close to a display focused on the infamous Abu Ghraib prison in Baghdad.

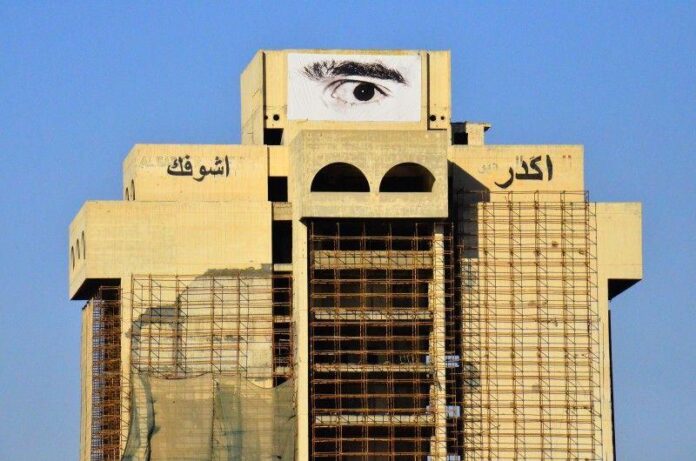

The artists Sajjad Abbas, Raed Mutar and Layth Kareem protested against their work being shown at the Hamburger Bahnhof without their consent where photographs by the French artist Jean-Jacques Lebel are also on display. Another artist, Sajjad Abbas, requested that his video and banner, I Can See You (2013), be removed from the gallery; these works are now on show in another venue.

A spokesperson for the Berlin Biennale says: “Mutar’s and Abbas’s works were exhibited close to the work by Lebel. They are now being shown in different venues (Akademie der Künste Pariser Platz and KW Institute for Contemporary Art). Layth Kareem’s work is still presented in a video cabinet in a different room of the same venue.”

The curator Rijin Sahakian initiated the letter which was originally published in ArtForum. She writes: “The Biennale made the decision to commodify photos of unlawfully imprisoned and brutalised Iraqi bodies under occupation, displaying them without the consent of the victims and without any input from the Biennale’s participating Iraqi artists, whose work was adjacently installed without their knowledge.”

Lebel has enlarged images of tortured prisoners at the prison that were taken by US soldiers and leaked in 2004, a year after the US-led invasion of Iraq, for his installation entitled Poison Soluble (2013). In a statement on the Biennale website, Lebel says he has “printed and enlarged the colour snapshots taken by the torturers, interspersing them with black-and-white press images of Iraqi towns devastated or completely obliterated by the US Air Force”.

Lebel’s photographs are on show in a “labyrinth-like installation. In the exhibition, the installation is, and has always been, behind a curtain with a sign in front of it informing visitors that images of violence can be seen on a large scale and can trigger retraumatising reactions,” the Biennale spokesperson adds.

Raed Mutar’s Untitled (2012)

Courtesy Rijin Sahakian © Raed Mutar, Photo: Eric Tschernow

Kareem’s 2014 video The City Limits examines the psychological effect of bombings and destruction while Mutar’s painting Untitled (2012) reflects on his time sharing a studio with two artist friends in Baghdad. Sahakian explains how the exhibition was initially laid out. “I view Abbas, Kareem, and Mutar’s cutting, sweeping work, and a curtain. The second half of Abbas’s work is on the other side; I have to go through the curtain to see the rest of his installation. As I do, I am presented with an installation by Lebel [Poison Soluble]. It is composed of images printed to life-size: the charred skin, limbs, and hooded faces of the Iraqi men abused and murdered at Abu Ghraib,” she writes.

Sahakian outlines her Biennale role in the open letter, saying: “I had introduced Abbas and Kareem’s work to the Biennale, lent a painting by artist Raed Mutar to the show, and contributed catalogue texts on their work. I first got to know each of these artists in Baghdad, where they lived and made the selected works between 2011 and 2014.”

Video still from Layth Kareem’s The City Limits (2013)

Kareem publicly denounced the display in a conversation held as part of the Biennale’s public programme. Sahakian, who was also part of the talk, writes in the open letter: “Our final exchange addresses his video work—created with friends and other Baghdad residents who share their experience of living with the constant spectre of violence—in contrast with the Abu Ghraib work, which reproduces the asymmetrical power inherent in the photos void of respect or repercussion.”

The letter continues: “Kareem responds by calmly informing the audience that he has family members who were imprisoned at Abu Ghraib. He points to what is missing in the bright yellow trigger warning at its entrance: ‘They haven’t given their permission. I can’t accept this.’ A few minutes later, Kader Attia, the lead curator of the Biennale, is onstage, providing a rationale for the work’s inclusion: ‘We should understand the photos must be seen for political change to take place.’”

Earlier this year, Attia told Arab News: “With these works, we are looking at the space in between aggressors and victims. All crimes unify the victims and the perpetrators, psychoanalysts know that.”