The survey exhibition of the American artist Carolee Schneemann’s 60-year career, Body Politics, at London’s Barbican Art Gallery, has rightly been hailed as a landmark assessment of a feminist pioneer whose radical explorations and celebrations of female experience and sexuality reverberate today. But tribute is also due to another hugely important figure from the next generation who blazed what was arguably just as radical and transgressive a trail in her unorthodox and multifarious investigations into sensation and identity. The British artist Helen Chadwick’s career may have been cut tragically short—she died unexpectedly in 1996 from a heart condition at the age of 42—yet her reach was long.

Whether she was casting male and female piss holes in the snow, entwining blonde hair with pig’s intestines, combining flower petals with cleaning fluids or fabricating a fountain of molten chocolate, Chadwick’s art played with and off taboos, clichés and artistic conventions in order to interrogate who and what we are. “My apparatus is a body x sensory system with which to correlate experience,” she said.

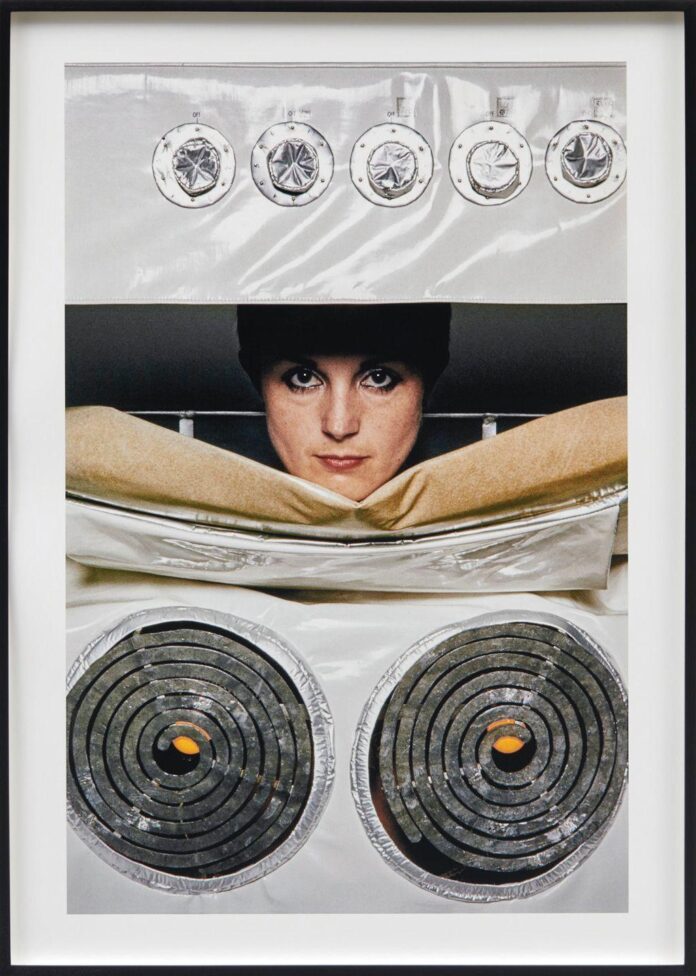

What we now take for granted in the way artists push at the boundaries of materials to interrogate notions of acceptability and preconceptions about identity and gender were in Chadwick’s work right from the start. Currently on show in the exhibition On Sexuality, at London’s Richard Saltoun Gallery, is Chadwick’s Domestic Sanitation, a film of her 1976 degree show performance at Brighton Polytechnic, in which four women, including Chadwick, parody elaborate rituals of cleaning and grooming. Their costumes are made from latex painted onto their bodies and emblazoned with prominent patches of pubic hair made from fluff and feathers, described by Chadwick as “pre-punk erotic artefacts”. Another early performance survives as a series of photographs in which the artist and friends wear sculptures of gendered kitchen appliances in a humorous revolt against domestic servitude.

Long before Damien Hirst put animals into his art, Chadwick was working with the bodies of fish, fowl and assorted beasts. Her exhibition Of Mutability at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in 1986—for which she became the first woman to be shortlisted for the Turner Prize—presented a profusion of flora and fauna in a work called The Oval Court. It included a lamb, a goose, a squid, several rabbits, pieces of offal and a giant skate, all of which Chadwick arranged and copied on a then cutting-edge colour photocopier. Ghostly pale against a rich cobalt blue background, the images of these spectral beasts were then set adrift amid more photocopies of fruit, vegetables and the artist’s own naked body, adorned with ribbons, lace and foliage.

‘A fresh aesthetic order’

Unlike Schneemann’s Meat Joy (1964), where male and female performers writhed naked in a filthy slurry of raw fish, meat and poultry, Chadwick’s Oval Court was meticulously orchestrated and arranged. Although her work often dealt with unruly sensations and visceral physicality, it was always pristine in its presentation.

The Oval Court now belongs to London’s Victoria & Albert Museum, and this magnum opus is the subject of a new book by the writer and academic Marina Warner, who examines its many and various sources and references from mythology, literature, and cultural and art history. Warner notes that in The Oval Court, Chadwick was searching for “a fresh aesthetic order” and points out that this work formed the seedbed for the artist’s subsequent use of provocative and often problematic materials in order to “unsettle normative binary oppositions between nature and culture, male and female, time and stasis… purity and decay, beauty and ugliness”.

Later examples of this rich quest include Chadwick’s 1994 exhibition at London’s Serpentine Gallery, which had at its centre Cacao, a giant fountain of molten chocolate, and a room containing 12 bronze hermaphrodite Piss Flowers made from Chadwick and her male partner urinating into snow and casting the resulting cavities. Shortly before her death Chadwick had been working with King’s College Hospital’s assisted conception unit to make a series of sculptures in the form of jewellery incorporating photographs of the cell structures of preimplantation embryos that would otherwise have been left to perish. Rife with complicated and contradictory readings, this memento mori also stands as a memorial to an artist who still had so much more to say and do.

• On Sexuality: Helen Chadwick & Penny Slinger, Richard Saltoun Gallery, until 10 January

• Carolee Schneemann: Body Politics, Barbican Art Gallery, until 8 January