At the end of November 2013, a new pavilion opened at the Kimball Art Museum. The project was created by Renzo Piano Building Workshop and local architects Kendall/Heaton Associates. The new building of the Kimball Museum in Fort Worth (Texas, USA) is located near the Louis Kahn’s vaulted monolithic building from the 70s. The creation of Piano “supports” the famous neighbor with the choice of concrete as the base material and the rhythm of vertical supports, but differs in composition: it is two volumes connected by transitions. The new structure also highlights the underlined contrast of a solid concrete structure with weightless glass walls and a transparent roof with an area of almost 2000 square meters.

The glass and steel roof structure is supported by powerful twin beams made of solid Oregon pine. There are 29 pairs in total. The length of each beam is more than 30 m. The roof structure of glass and steel is supported by powerful twin beams of solid Oregon pine. These elements create a kind of bewitching rhythm, which is subject to the architecture of the building.

Object Renzo Piano Building Workshop was built using resource-saving technologies. Thus, thanks to photovoltaic elements on the roof, the new pavilion requires three times less energy than the Kana pavilion, although their area is approximately the same. In the east wing, apart from the glazed foyer, there are two galleries with oak floors, in the west wing there is a conference hall, another exhibition space, classrooms, and a small library. Underground there is a garage connected by stairs to the lobby of the pavilion.

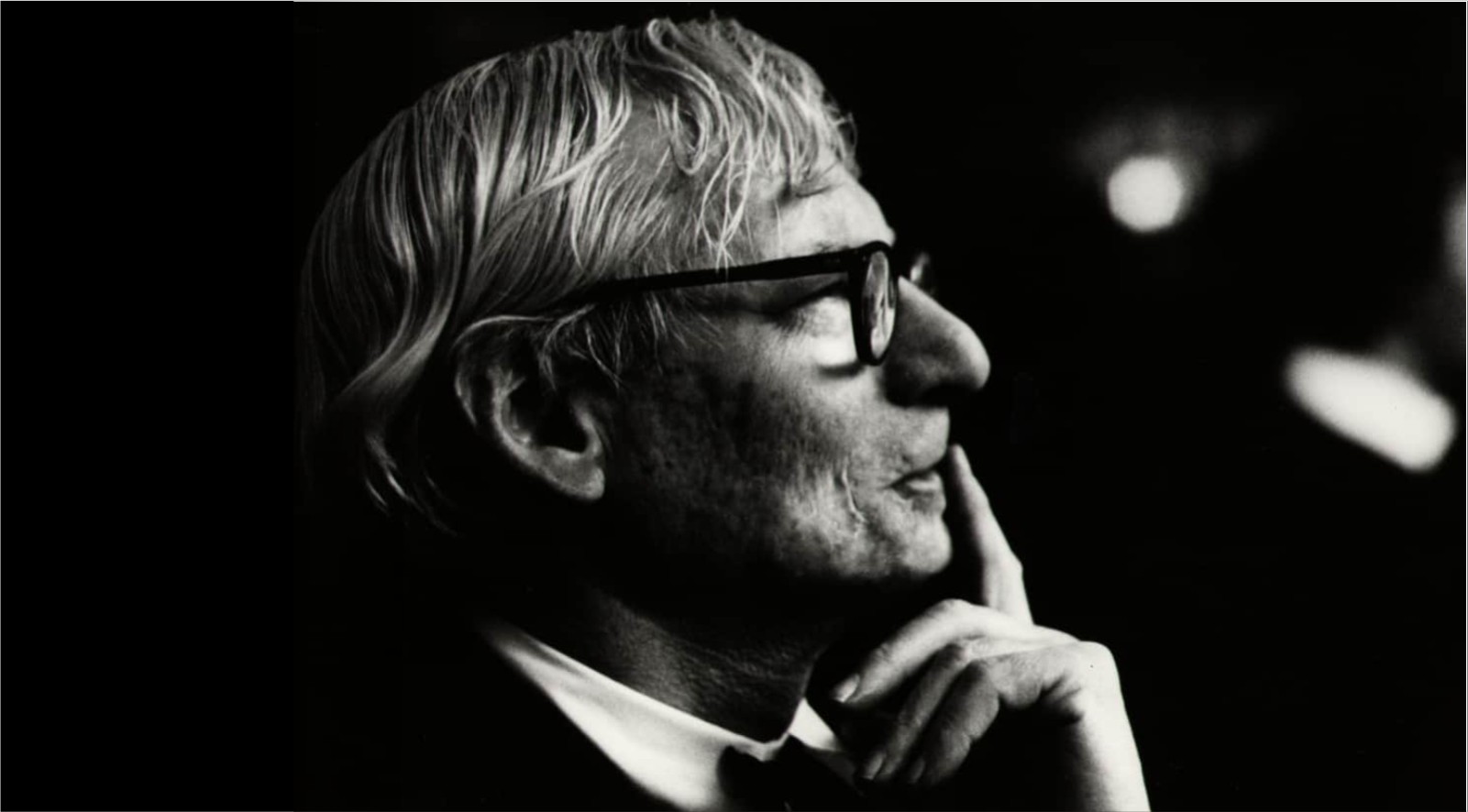

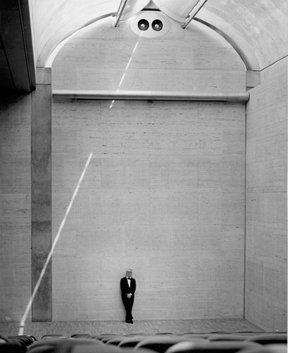

The American architect Louis Kahn (1901-1974) did not create many architectural structures, but a few of his masterpieces make such a piercing impression that he can safely be placed next to such outstanding masters as Wright, Corbusier, Mies, and Aalto.

However, unlike the creations of these brilliant architects, the architecture of Kan goes beyond modernism. His amazing metaphysical structures do not belong to his time, and therefore they should be considered as a separate phenomenon. With each passing year, it becomes more and more obvious. During his career, the architect not only built very few buildings but also scattered them around the world. And his most outstanding projects have been in such remote places as Ahmedabad (India), Dhaka (Bangladesh), La Hoya (California), and Fort Worth (Texas).

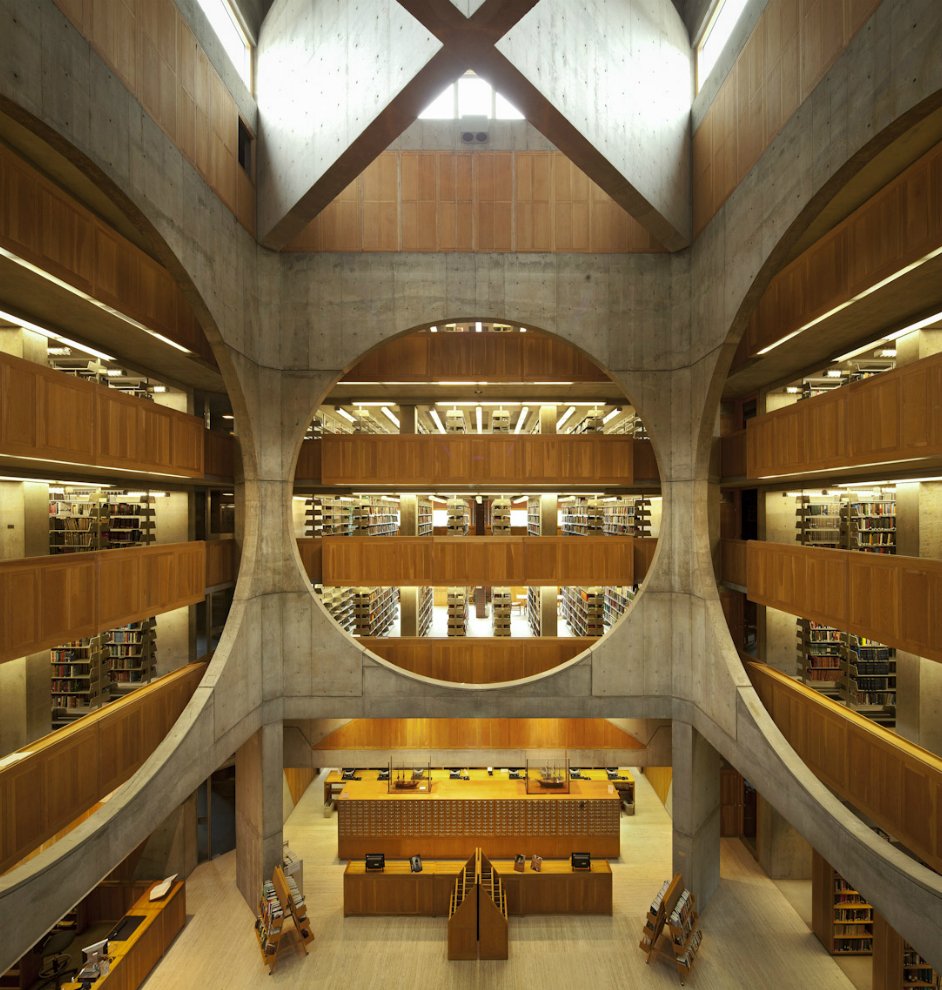

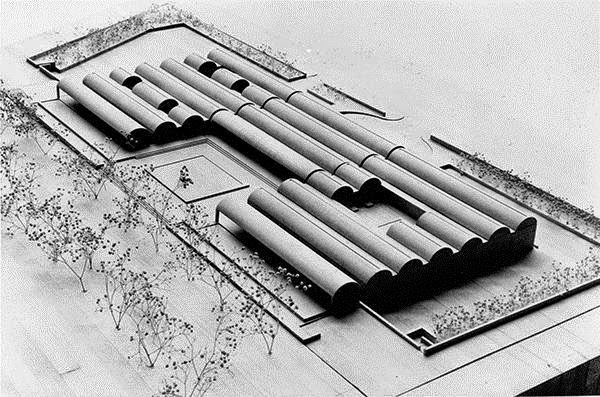

Fort Worth, according to Cana himself, has his best work, the Kimball Art Museum (1966-1972). The architect’s original goal was to invent a method of penetrating the room with natural light in such a moderate amount to emphasize the beauty of pure architectural form and prevent direct sunlight from entering the works of art.

Fort Worth, according to Cana himself, has his best work, the Kimball Art Museum (1966-1972). The architect’s original goal was to invent a method of penetrating the room with natural light in such a moderate amount to emphasize the beauty of pure architectural form and prevent direct sunlight from entering the works of art.

The quality of natural light is the main thing that fascinated Kan in his work. From project to project, he went back to his own techniques to find the most sophisticated solution. As for the appearance of Kan’s buildings, the master never tried to make them look like something known or familiar. They look more like ancient ruins. However, it was them that inspired the architect – English and Scottish castles, Egyptian pyramids, Greek temples, aqueducts and vaults of the Romans, the towers of San Gimignano, and the like.

There is a spirit in Cana’s buildings, which he managed to capture in the drawings he made in Italy in 1950-51 when the architect was invited by the American Academy in Rome to study archaeological sites of antiquity. After years of research, Kan rediscovered techniques for transforming the ruins of the ancient world into modern buildings as early as his maturity.

Primitive, abstract, devoid of subjective gestures, mystical, thoughtful, strange, fragmented, massive, strict – these are the words that usually describe Kan’s creations.

Vincent Scully, a prominent American historian, and professor of architecture at Yale University, which Philip Johnson called the most influential teacher of architecture in history, once noted: “Perhaps only a few Russian novels, especially Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, come to mind among the works of art, which can be compared with the works of Kan in terms of depth and severity.

Kan’s works are convincing in themselves, without any reference to contextuality. They represent the most valuable thing in the aspirations of modernism – to invent a new reality, to invent everything in its own way.

The way Kan represented his museum, he said well: “I’m working on an art museum in Texas. In this project, I feel that the light in the halls, structured in concrete, will shine like silver. I know that natural light should only penetrate the art gallery to a small extent. The idea is to make a museum room out of sequentially constructed rooms covered with cycloid vaults with a single span of 30.5 m long and 7 m wide. Each of these rooms is crowned with a slit facing the sky and a mirror-shaped element to reflect natural light in the vault. Space will fill the light of shimmering silver without directly affecting the works of art, and it will allow visitors to experience the time of day by the intensity of sunlight.

A special impression of the Museum building, both inside and outside, is made by the material from which it was built. It is mainly raw concrete. Kahn paid special attention to the quality of construction. Moreover, he did not strive to create perfectly smooth surfaces, seams, and edges. On the contrary, he was deeply convinced that all this should be indicative of the construction methods and principles. Kan had no secrets. His concrete is very different from the close to perfect concrete that is located across the street at the Museum of Modern Art of the architect Tadao Ando. While Ando’s concrete is dematerialized and is perceived almost like glass, Kan’s concrete is warm and organic. It is a fine manual and soulful work.

A special impression of the Museum building, both inside and outside, is made by the material from which it was built. It is mainly raw concrete. Kahn paid special attention to the quality of construction. Moreover, he did not strive to create perfectly smooth surfaces, seams, and edges. On the contrary, he was deeply convinced that all this should be indicative of the construction methods and principles. Kan had no secrets. His concrete is very different from the close to perfect concrete that is located across the street at the Museum of Modern Art of the architect Tadao Ando. While Ando’s concrete is dematerialized and is perceived almost like glass, Kan’s concrete is warm and organic. It is a fine manual and soulful work.

The museum was built and is funded by the renowned businessman and philanthropist Kay Kimbell (1886-1964) and his wife Velma Fuller Kimbell (1887-1982). In 1964, this childless couple donated their entire fortune (Kimbell owned about seventy corporations) to a specially organized art foundation to create a “world-class museum. In response to such a generous gesture, the city allocated an area of nearly four hectares in the area where the centenary of Texas’ independence from Mexico was celebrated in 1936. The neighborhood soon became a major cultural district with many exhibition centers and museums.

The museum was built and is funded by the renowned businessman and philanthropist Kay Kimbell (1886-1964) and his wife Velma Fuller Kimbell (1887-1982). In 1964, this childless couple donated their entire fortune (Kimbell owned about seventy corporations) to a specially organized art foundation to create a “world-class museum. In response to such a generous gesture, the city allocated an area of nearly four hectares in the area where the centenary of Texas’ independence from Mexico was celebrated in 1936. The neighborhood soon became a major cultural district with many exhibition centers and museums.

The Kimball Museum’s collection includes statues from the Greek and Romanesque periods, ancient art from Southeast Asia, canvases and sculptures by European Renaissance artists and masterpieces of modernism to the mid 20th century.

In conclusion, there are a few of Kan’s remarks. They clarify a lot in his work.

“The sun never thought about its greatness until its rays touched architecture.”

“You can’t consider space architectural if there’s no room for natural light.”

“I don’t like complete and certain spaces. It’s different if you can change them every day.”

“When you know all about the building you have yet to build, your knowledge is deceptive. The building tells you about itself as you grow and find yourself.”

“I do not believe in the notion of necessity as a driving force. Necessity is something ordinary and every day. But the desire is quite different. Desire foreshadows necessity. We are driven by desire.”