Rafael Viñoly, one of the most admired architects of his generation and creator of landmark buildings around the world, has died, aged 78.

The Uruguayan-born, New York-based designer was best known for two headline-making structures: 20 Fenchurch Street, London, nicknamed the “Walkie-Talkie” for its distinctive, flared outline (completed 2014), and 432 Park Avenue (completed 2015), the first and most elegant of the super-tall, ultra-thin residential skyscrapers that have sprung up across midtown Manhattan in a glass-and-aluminium, 21st-century take on the status-symbol towers of 14th-century San Gimignano. Viñoly was also the subject of intense public scrutiny for a visionary but unbuilt scheme created with Frederic Schwartz and the Think Team: a 2003 proposal—soaring lattice-patterned structures to fill the space once occupied by the Twin Towers—for the competition to rebuild the site of the World Trade Center destroyed in the 2001 terrorist attack on New York.

Headline-making: Viñoly’s 342 Park Avenue, New York City, and 20 Fenchurch Street, London Rafael Viñoly Architects

Viñoly’s works for the world of art and culture include the Kimmel Center for Performing Arts, Philadelphia (completed 2001, a vast barrel-vaulted statement in steel and glass, housing two auditoriums); the Nasher Museum of Art, Duke University, North Carolina (2005, a pentagram of pavilions on a wooded knoll); the Brooklyn Children’s Museum (2005, low-slung, L-shaped and coated in yellow ceramic tiles); the substantial extension and renovation of the Cleveland Museum of Art (2004-12); and the new Fortabat Collection building (2008) in Buenos Aires, to house the collection of Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat. That collection includes JMW Turner’s Juliet and her Nurse (1836)—which set a record for art at auction of $6.4m plus commission when sold at Sotheby Parke Bernet by Flora Whitney Miller (with some of the proceeds going to the Whitney Museum) in 1980—and Andy Warhol’s 1980 Portrait of Mrs. Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat. In New York he designed a new home for Jazz at Lincoln Center (2004), on the fifth floor of Time Warner Center, with an almost outrageously expansive view from one of its auditoriums through a 50ft-high glass wall across Columbus Circle to Central Park.

Viñoly’s Firstsite visual arts centre, Colchester (completed 2011), winner of the 2021 Art Fund Museum of the Year prize Photograph: Mark Atkins

In Britain, Viñoly’s museum work includes the gold-skinned crescent-shaped Firstsite visual arts centre, in Colchester (completed 2011), winner of the 2021 Art Fund Museum of the Year prize. The prize judges commended FirstSite as an “outstanding example of innovation and integrity”. “At their core is powerful, engaged contemporary art, housed in a gallery that gives space for everyone,” the Art Fund’s director and chair of the judging panel, Jenny Waldman, said, “from artists to NHS staff to local families and refugee groups.”

Viñoly designed the Curve Theatre, in Leicester (2008), a near-transparent structure with fluid links between front of stage, backstage and its auditoriums, and created the 2016 masterplan for the redevelopment of Battersea Power Station, one of the best-loved landmarks of London’s built heritage, now in its third phase, where the Giles Gilbert Scott power station has been remodelled by Wilkinson Eyre, with rippling avenues of apartment blocks designed by Frank Gehry (Prospect Park, completed 2022) and Foster + Partners (The Skyline).

Viñoly had an acute sense of the importance of the visual arts. In his practice’s head office in Manhattan, a stone’s throw from Brooklyn Bridge, he hung reproductions of works by Diego Velazquez and Rembrandt van Rijn—surroundings designed to make his team more cultivated by osmosis.

An admirer of Louis Kahn

As an architect he cared less in his buildings for displays of personal style or visual effects and more for the successful solution of an architectural problem. In an era when every “starchitect” worth the name was chasing glamorous museum commissions, Viñoly was just as happy to be recognised for his work with laboratories, hospitals and universities. The architects he most admired included, historically, Andrea Palladio, and in the modern era Oscar Niemeyer, creator of Brasilia, and the minimalist master Mies van der Rohe, whose Seagram Building (completed 1958) was Viñoly’s favourite in New York. But the forebear whose buildings appeared to have moved him the most was the Philadelphian magus Louis Kahn.

In a 2021 interview with the pianist Kirill Gerstein, Viñoly spoke about Kahn’s celebrated Salk Institute building in La Jolla, California (1962-65), founded by Jonas Salk, the celebrated developer of a successful polio vaccine. First, Viñoly noted, the Salk Institute is a great laboratory—one where ground-breaking research in molecular biology is still done 60 years on. The acid functional test. But, at the end, he said, “it does one thing. You walk [between the two embracing wings] overlooking the ocean. All of a sudden you feel you are good. You feel somehow that something has touched you that has changed the plane of the experience. Being elevated. It’s like late Rembrandt.” He goes on to describe his experience of visiting Rembrandt: The Late Works (2014-15) at the National Gallery, in London. “An unbelievable show. I went around like 16 times … what you see—the location, the societal environment, and whatever kind of stylistic or critical positioning you make—is overcome by something that conveys the sense of transcendence.”

He found an equivalent transcendence in architecture through the art’s finer points rather than visual drama. In a 2008 interview he talked about the in-person experience of another of Kahn’s masterpieces, the Kimbell Art Museum in Forth Worth Texas (opened 1972), whose monumental use of barrel-vaulting is referenced in Viñoly’s work including the Kimmel Center and the Fortabat Collection. “We all have seen it. We have pictures of [the Kimbell]… [but] when you come into this place,” Viñoly said, “the experience has nothing to do with what you see. It is about what you feel, and that is what makes great architecture—the subtleties.”

A cultivated upbringing in Buenos Aires

Viñoly was born in 1944 in Montevideo, the son of Román Viñoly Barreto (1914-70), a prominent Uruguayan-Argentinian film and stage director and screenwriter, and Maria Beceiro, a maths teacher and former architecture student. It was a cultivated household where the architecture of Le Corbusier, the art of translation, or the conducting of Arturo Toscanini might form part of the table talk.

The family moved to Buenos Aires when Rafael was five years old, after his father was invited to the city to direct Wagner’s music drama Die Walküre at the city’s Teatro Colón. Rafael’s sister Ana Maria became an actress before qualifying as a doctor of both medicine and psychology. His elder brother, Daniel, became a visual artist. Rafael started piano lessons at the age of five, with an Italian émigrée teacher from a sophisticated family in Florence. “As in many cases with a music teacher like this,” Viñoly said in a 2017 interview, “I learned many more things than just how to play. She introduced me to philosophy and the contemporary arts.”

Viñoly showed great natural talent and seemed on course to become a professional pianist—in a city where he was a younger near-contemporary of two Argentinian giants of the instrument, Martha Argerich and Daniel Barenboim (both of whom remained lifelong friends)—before he altered trajectory to study architecture at the University of Buenos Aires. He earned his diploma in architecture in 1968, after setting up his first practice, Estudio de Arquitectura, with six partners, four years earlier. His first substantial public design was the Argentine Industrial Union Building (1968), a glass tower, overlooking the port of Buenos Aires.

Architectural student and architect

Over the next decade, during a period of marked political instability and serial changes of government—students were killed when the university was raided following a military coup in 1966—Viñoly and his partners developed one of the leading practices in Argentina, building private homes and large residential projects. Three of the most important schemes, all of which won international attention, were completed in 1978, the year that Argentina hosted the football World Cup, and two years after a military junta had deposed Isabel Peron as president and taken full control of the country.

For the World Cup, Viñoly designed a new 45,000-seater stadium in Mendoza, Argentina’s fourth largest city, in the foothills of the Andes, as well as Argentina 78 Televisora (A78TV)—renamed ATC Argentina Televisora Color in 1979—the television production centre for the World Cup, with three massive soundproof studio buildings arranged distinctively in line across an urban park setting. In the same year, work was completed on Terraces of Manatiales, in Punta del Este, Uruguay, a gently terraced complex of 92 beachside houses linked by barrel-vaulted passageways.

In 1978, the year of his “establishment” success, heightened by Argentina’s home victory in the World Cup, Viñoly had his house searched by the military regime in an era of anti-Communist hysteria. During the raid, a Larousse dictionary was taken by the police to be code for “La Russie”, Viñoly told the New York Times in 2003. It was an era when “no one was above suspicion” and the “Dirty War” against dissidents and minorities was spreading. Viñoly and his interior designer wife Diana Braguinsky decided it was time to leave Argentina, and took their family to the US in late 1978. Viñoly lectured in the Harvard University Graduate School of Design before the family settled permanently in New York. He worked for a time in property development, and requalified as an architect in the US before setting up Rafael Viñoly Architects in Manhattan in 1983.

A feeling for civic space

From the practice’s New York base, Viñoly and his long-standing vice-president, Jay Bargmann, built up an international practice over four decades. If the practice has a calling-card style it is not pictorial but its demonstrable focus on systems, a prowess in making complicated civic projects work, and its systematic use of models to perfect a design and its “constructability”. The use of large-scale study models was another element that Viñoly felt he had inherited from Kahn.

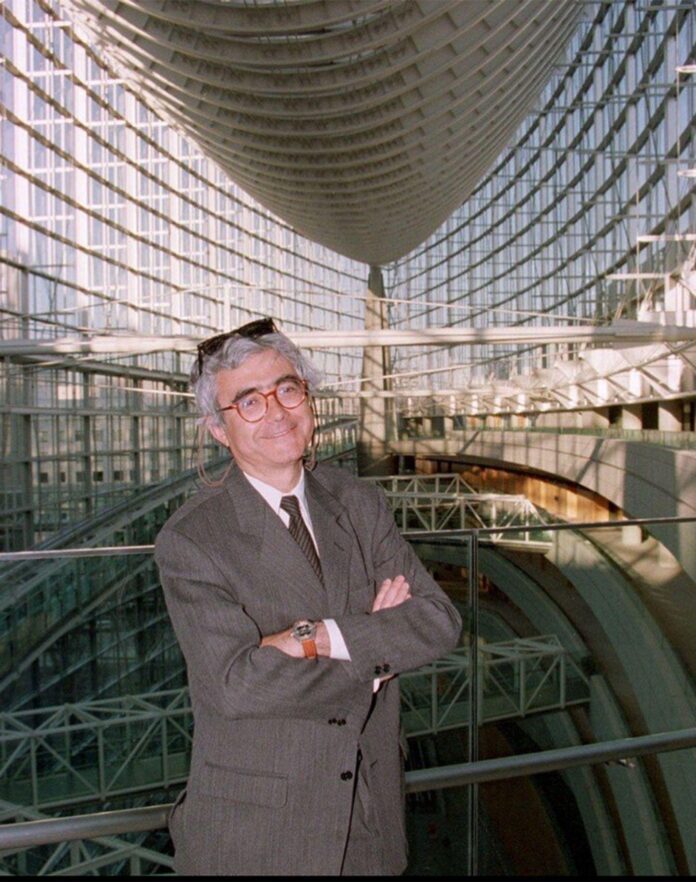

The project that brought the Viñoly approach to maturity was his winning competition entry for the Tokyo International Forum (1989-96), an arts centre and civic complex, spread over six acres, with two stations and four subway lines on either side, containing a landscaped urban plaza, with four performing arts spaces suspended above, and a massive Glass Hall with a 228m-long truss hovering above it. It was the project that made Vinoly’s international name, one that he referred to as “the Grand Central Station of Tokyo”.

To mark an exhibition in Chicago about his Tokyo project, Viñoly gave a lecture on The Making of Public Space at the College of Architecture and Urban Planning, University of Michigan, in March 1997. That “making of public space” was one of the most memorable aspects of his work over the next 25 years. What the late Richard Rogers did for public spaces in London and Paris, Viñoly did for a series of cities including Tokyo in 1989-96; New York (the public view to and from Jazz at Lincoln Center); London (the Battersea Power Station master plan); Philadelphia, (the Kimmel Center); Boston (Boston Convention & Exhibition Center); and Cleveland, Ohio.

Viñoly’s eight-year, $320m enlargement of the Cleveland Museum of Art (completed 2012), involved the restoration of the 1916 Greek Revival building and of the 1973 education wing designed by the modernist master Marcel Breuer, as well as the addition of new west and east wings and a vast new wave-like glass and aluminium central atrium. Katharine Lee Reid, the museum’s director and mastermind of the scheme, likened the new atrium to an Italian piazza that would give Cleveland a year-round gathering place at the centre of University Circle, the city’s educational and cultural heart.

A feeling for civic space: Viñoly’s monumental “Italian piazza”, part of his enlargement and renovation of Cleveland Museum of Art (2004-12) Usaf 1832

The challenge of ‘public’ architecture

With high-profile commissions around the world, Viñoly and his practice attracted the accompanying public attention and substantial doses of Schadenfreude directed by the press at the ambition—often described as hubris—of the developers and tenants that Viñoly worked for.

Viñoly found himself at the centre of a particular brand of New York power politicking when his Think Team (which included his fellow architects Frederic Schwartz, Shigeru Ban and Ken Smith) was shortlisted and then announced as one of the two final contenders for the rebuilding of the World Trade Centre at Ground Zero in a 2002-03 competition run by the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation. The Think Team’s rival in the final run-off was Daniel Liebeskind, architect of the acclaimed Jewish Museum in Berlin. The governor of New York, Georg Pataki, and the developer Larry Silverstein were other more-than-interested parties. In an intense exchange of press briefings. Viñoly found himself criticised ad hominem in one Wall Street Journal article for the narrative around his political exile from Argentina in 1978.

A year before 20 Fenchurch Street (the “Walkie Talkie” building) was completed on a site overlooking the River Thames in 2014, there was a public fuss when the owner of a car parked below the site reported that reflected sun from the building’s parabolic, glass facade had melted the plastic trim of their car’s dashboard. Viñoly was disarmingly frank in his response, when interviewed by Oliver Wainwright of The Guardian. “We made a lot of mistakes with this building,” Viñoly said, “and we will take care of it.” The Guardian reported that “the original design of the building had featured horizontal sun louvres on its south-facing facade, but these are believed to have been removed during cost-cutting as the project developed”.

Viñoly was no less frank about some of the compromises he felt he had had to make at 432 Park Avenue, the pencil tower skyscraper, whose unmissable outline and multi-billionaire tenants had been criticised as emblems of New York’s growing inequality. He later apologised for reporting off-the-record comments in which “I expressed frustration, inartfully, about the consequences of my profession’s diminished position in the real estate development eco-system.” The building has won plaudits, for the jewel-like elegance of its facade—with its layers of six 10ft-by-10ft square windows likened to an extruded version of a work by the minimalist Sol Le Witt—and has also been subject to tenants’ complaints against its developers, gleefully welcomed by the building’s critics, for flooding, malfunctioning lifts and noise in high winds.

Viñoly’s frustration speaks volumes of the chagrin that he and his peers sometimes felt when held to account as an architect working on grand projects in the public eye.

Feeling, not understanding, architecture

Rafael and Diana Viñoly often collaborated on interior projects and their son Román was a fellow director of the practice. The family lived between Tribeca, New York, a house in Long Island where Rafael built a piano house for one of his collection of nine concert grands, and a base in London. Rafael played daily, whether at home or in the office (where he oftened worked on Sundays, and slept on a mezzanine to isolate from his family when he caught Covid).

A widely quoted remark of the composer Igor Stravinsky—”I have never understood a bar of music in my life, but I have felt it”—serves as an apt parallel to the music-loving Rafael Viñoly’s hopes for how people might experience his buildings. He wanted people to sit down and look with attention. Not to understand, but to receive. To feel.

Rafael Viñoly Beceiro; born Montevideo, Uruguay, 1 June 1944; Fellow American Institute of Architects 1993, Medal of Honor 1995; International Fellow Royal Institute of British Architects 2006; married 1969 Diana Braguinsky (one son; two stepsons); died New York City 2 March 2023.