There are two fashion designers that belong in particular to the art tribe: Yves Saint Laurent and Vivienne Westwood.

Saint Laurent, the exquisitely refined art collector, tripped through the world’s art collections and savoured, borrowed and rendered in cloth, be it Mondrian’s 1930 Composition with Red, Blue and Yellow, Picasso’s 1949 Dove or an 18th-century Coromandel screen. In the same way, Westwood spun Kolman Helmschmid’s early 16th-century suit of armour, into a Harris tweed jacket padded with armoured panels, printed Boucher’s putti from Venus and Vulcan (1754) across corsets and raincoats, and used Keith Haring’s New York subway graffiti of 1980-81 on cotton streetwear, one example of which is listed on 1stDibs.com for £36,000. Both designers created heartstopping and wearable beauty.

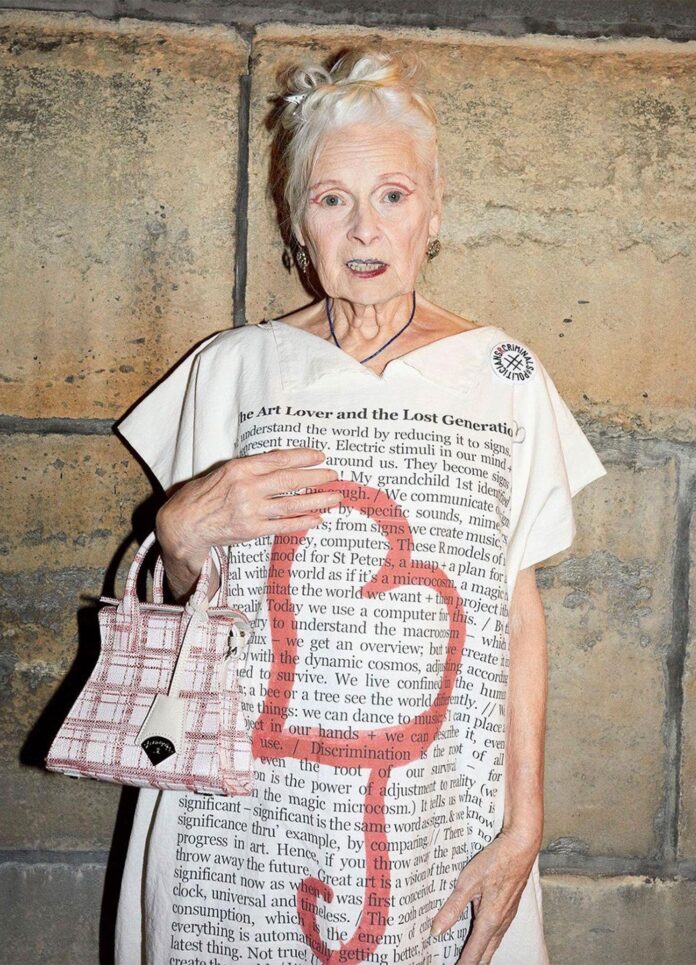

Many of those in the fashion industry who would later acclaim Westwood’s creativity and be keen buyers—even collectors—of her clothes, for a long time did not get it. Her clothes, they scoffed, were unwearable, badly made, ridiculous. They were none of these things and many of the early sceptics later became avid collectors of vintage Westwood.

Westwood was talking to us through her clothes; telling us what mattered, what we must protect, value, or reject. Unlike Saint Laurent, she did not have a privileged education. She had an even better one: that raw, unedited, unique education of the auto-didact. Wonder at it, steal it, elide it, create from it: that was her working practice. Her inventiveness was formed by actively seeking out those she dubbed her “gurus”—people from whom she could learn. She hungrily sucked out of them their very mental marrow.

Malcolm McLaren, the metropolitan art student, her long-time lover, was her first guru; he taught her British street rebellion, French Situationism, American pop culture. Gary Ness, a philosophy teacher from Canada and her second guru, taught her élitism and the philosophy of Ancient Greece.

I met her in 1981 and she often asked me to have dinner with her at Khan’s curry house in Paddington, to talk about literature and art. She was working with Keith Haring, some of whose stick figures referenced incest. Had she read, I asked, Thomas Mann’s study of evil, magic and incest, The Holy Sinner, or seen the early “graffiti” of the Palaeolithic cave paintings at Lascaux?

Though McLaren was undeniably formative in mind-sculpting his lover, it was Westwood’s enviable drive to experiment, improve upon and declaim through her clothes that made her such an important designer. She would not take anything for granted. Take a sleeve, for example. Why should it be conventionally inserted? Why not twist it, cut it on the bias? Look how it gives the body an almost kinetic sense of movement.

Objets trouvés? I can do that, she thought. I may not want to eat the chicken from the takeaway across the street from my shop in World’s End—the one at 430 King’s Road, Chelsea, where Westwood and McLaren sold clothes under a sequence of names including SEX and Seditionaries, and Westwood emerged as the voice of Punk at its apogee during the Silver Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II—but let’s boil up those chicken bones, drill holes in them and write provocative messages across a Punk T-shirt.

Again, Westwood looked with new eyes at images of pirates. The very disorder of their ill-fitting clothes lends the wearer a post-coital déshabillé. She went off to the Art Library at the Chelsea Town Hall and then the National Art Library at the Victoria & Albert Museum, found books on 18th-century pirates—including Norah Waugh’s The Cut of Men’s Clothes—and noticed that these clothes hung suggestively rather than following the body precisely. Out of this research came her Pirate Collection of 1981, Westwood and McLaren’s first catwalk show. If you try on the trousers, you will see that none of the buttoned flies are cut straight down the crotch, they lie diagonally across the abdomen, lending an air of sweet disorder. And sweet disorder was her leitmotif.

From Ness, she discovered that Plato advocated rule by philosopher kings and that the Demos should defer to their greater wisdom. I gave her a copy of Isak Dinesen’s Daguerretypes and Other Essays in which she read an essay on body shapes. Dinesen observed that in the past, when hunger was commonplace, the rich favoured voluptuousness as it trumpeted their full stomachs. But in the Age of Plenty, when many bellies were filled with carbohydrates and sugar, the rich differentiated themselves with a fashionable thinness, a change in taste that came about at the end of the 19th century. Westwood digested these two pieces of information, Plato and Dinesen, and created a synthesis in dress.

She argued that she was against democracy because the man in the street was not equipped to make sensible decisions. Before the dawn of modern democracy, the elite were voluptuous and so she resolved to make a collection of elitist tailoring with padded buttocks and fleshy bosoms bursting out of corsets. She printed ancien regime images of French privilege, lifted from Boucher and Fragonard, across corsets and raincoats—the Wallace Collection, in London, was another favourite museum—so that people would understand that she did not favour the popular, the ordinary or the casual. Hence her famous Portrait collection, of 1990. She literally wore her learning on her sleeve.

Westwood was a perfectionist. Struggling to keep her head above water, as the bills piled up and as her personal life fell apart, she kept standards high. An established Camden Town tailor was admonished for imperfections. Experiments with print were repeated again and again to get it just right. Once she had reasonably solid financial backing, the standards were raised higher still. If you get to wear one of Westwood’s Duchess satin couture ballgowns, you are Marie Antoinette, and she wants you to really feel it.

When, in the early 1990s, I was asked by the well-known head of a leading publisher to discuss my proposal for a biography of Westwood, she sat and listened but kept repeating “but her clothes are unwearable”, and finally concluded that there would be little interest in such a biography. I politely thanked her for her time and headed for the door. As my hand reached out for the door handle, she called out, “I love your suit. Where did you get it?” Imagine my glee as I replied, “Westwood!”

It got me thinking. I had a page in a national newspaper and so I gathered together a collection of high-profile, professional women, including the founding editor of The Art Newspaper, Anna Somers Cocks, and dressed them in Westwood tailoring. They looked powerful, beautiful, free-thinking, brave.

This prompted the thought that the next step was Paris, especially given Westwood’s deep understanding and love for the clothes of Christian Dior. Surely Bernard Arnault, head of LVMH, must appoint her chief designer at Dior. She would be perfect. In 1991, I made an appointment with Dior’s Directeur Général, Daniel Piette, and Vivienne and I took her portfolio to Paris. The portfolio showed that she was a pioneer in so many fashions— too many to list. We were on the first flight out.

Vivienne, her ringlets dyed as red as pomegranate juice, was dressed in a clingfilm-tight, gold-printed velvet dress and sky-high, lace-up, platforms. I wore Westwood too, a Rob Roy black velvet jacket, buttoned in gold, a white lawn cavalier’s blouse frothing over the tight corset, velvet mini skirt, a slouchy tam o’shanter and six-inch high court shoes. As we strutted across the bleak concourse at Heathrow towards our gate, a plane from Delhi had just disembarked a crowd of sari-ed Indians who pointed then clapped as we walked by.

Surely, we would take Paris by storm. But no. I later learnt that Arnault calculated that Westwood could not be “controlled” whereas, some years later, he could control—to a point— John Galliano and Alexander McQueen, both of whom were heavily influenced by Westwood and were delighted to acknowledge it.

Rejection was a good thing. Westwood continued to perfect and make wonder, under her own steam and on her own terms, working latterly with her second husband, Andreas Kronthaler. It is little wonder that crowds snake around the block to see her museum retrospectives, including the show put on at the Victoria and Albert Museum, in London, in 2004, before it toured the world. It is no wonder that her vintage pieces cost thousands of pounds. I was not surprised that my students at Central St Martins Art School really wanted to know about Westwood. Show the young innovation and they “get it”.

Westwood is one of the great arguments why, as children queue at food banks, they must be given access to culture for free at museums. Who knows what that bright-as-a-button child, standing in front of a Caravaggio or a Duchamp, will invent or create that will move culture forward and enrich everyone’s lives and surroundings?

Of all Westwood’s soapbox platforming, Free Entry To Our Museums was her most important. She is a great exemplar of what that access can produce.

Vivienne Isabel Swire, born Glossop, Derbyshire 8 April 1941; OBE 1992; DBE 2010; married 1962 Derek Westwood (one son, marriage dissolved 1966), partner of Malcolm McLaren (one son); married 1993 Andreas Kronthaler; died London 29 December 2022.

- Jane Mulvagh is author of the biography Vivienne Westwood: an unfashionable life (1999)