Before the artist Charlotte Salomon was murdered in Auschwitz, she gave her life’s work to a non-Jewish doctor who was a friend. It was a series of more than 700 paintings that she had made in a year and a half while in hiding in France. “It is my life,” she is said to have told him.

The work, defies easy categorization: formally, it is multilayered, consisting of hundreds of gouache paintings on paper, some with transparent textual overlays; all with accompanied text. One might call it the first graphic novel. But it is more than just that. The work, subtitled “a play with music,” can also be read as a conceptual script for a theater.

Conceptually, the work operates on different levels. Salomon’s ambitious artwork is something like an autobiography of her tumultuous life, but also not quite. There are characters who look and act like her own family and friends, but their names are slightly changed. There is music that is meant to accompany these vividly painted scenes, which tell Salomon’s life story, about coming of age as a young woman and an artist in Nazi Europe.

With generosity and incredible detail, it shows what played out in Berlin as the Nazis rose to power: the persecution of her family; the death of her mother from suicide, and later her grandmother in the same way. It tells about her suffering in exile; it includes a confession to murder. But it is a work about triumph, to be sure. captures the birth of a brilliant female artist who found a lifeline in making art.

Not only is the work picturesque in the way it is painted and formally ground-breaking, Salomon managed to achieve something deeply intimate and personal but also universal—as Salomon put it herself, the piece is “something crazy special.”

The work, which survived the war and was retrieved by her parents, was donated to the Jewish Historical Museum in Amsterdam. Parts of the piece were exhibited at Documenta 13, curated by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, in 2014. It has made world tours, and inspired manifold interpretations. A new film debuted at the Jewish Film Festival in New York in January. Last November, an animated film starring Keira Knightley also interpreted Salomon’s story and work.

And yet, given that it is the largest known artwork made by a Jewish person who died in the Holocaust, Salomon is not yet a household name and should be. Her work is still largely overlooked by the wider public, and art historians and curators are still only beginning to engage with the artist’s monumental work.

On the occasion of a new exhibition of at the Lenbachhaus in Munich (running through September 10), Europe editor Kate Brown spoke with the exhibition curator Irene Faber, who is also curator of collections at the Jewish Historical Museum in Amsterdam, and an expert on Salomon’s life and art.

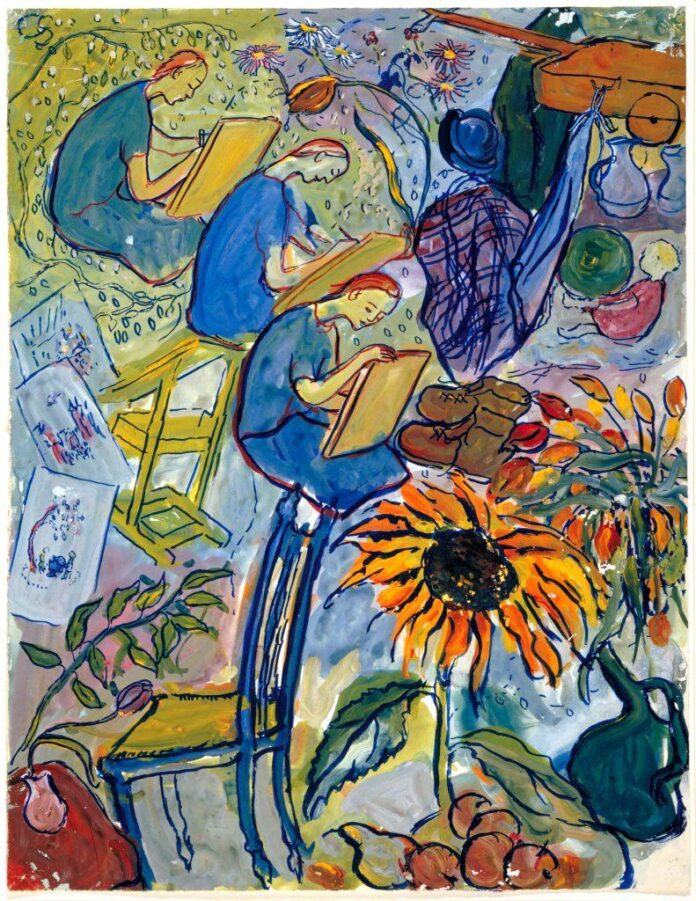

Charlotte Salomon, Selfportrait (1940-1942). Collection of the Jewish Museum Amsterdam. © Charlotte Salomon Foundation

Note: This interview has been edited for clarity. To hear the full audio version, tune into the episode on the Art Angle podcast.

It’s hard to know exactly where to begin with Charlotte’s story, but maybe we can start with the practical details. What is this work about?

The work is a series of 769 of paintings made by a young girl in her 20s; she painted her life in gouache. It’s a heavy kind of water paint. She painted her life to overcome her own sad story and to find out what was truth and what was a lie in her life. That is why the title is asking whether it is life or theater.

Can you explain a bit more about the form that it takes? It is a total work of art—Charlotte included within the paintings remarks about what kind of music should be played alongside.

She painted it in a way that one could make an opera of it and the texts are almost sort of . The paintings are done in a way that you could make a film of it. The scenes follow each other and are like a storyboard. This is really a very big scale idea for a young girl.

Charlotte Salomon, Gouache from Life? Or Theatre? (1940-1942) Museum Amsterdam / Collection of the Jewish Museum Amsterdam. © Charlotte Salomon Foundation. The text in the painting states “above the average.”

This work is largely autobiographical, as you mentioned. I think a good place to start is really to look at her own biography because this is her story. What setting was Charlotte born into? In what kind of a family was she raised?

It was a well-to-do Jewish family in Berlin. Her father was a surgeon. Her mother was a nurse, but stopped working when she married. Her mother had a history in her family of suicides, which was not known to Charlotte. She was a young girl when her mother committed suicide. She was nine years old and her father was left alone with her.

He married Paula Levy—she called herself Lindbergh because Lindbergh was better to sell her work as it was not a Jewish name. She was a very nice stepmother to Charlotte. Charlotte went to a classical high school, but did not finish. She had to leave because Hitler was coming to Germany.

She decided to go to the art academy. She was admitted there, even though she was Jewish, because they had to take a certain percentage of Jews. She didn’t finish as Jews were not treated very nicely there. In 38, the atmosphere in Germany was not very nice for Jews, in the period after the Kristallnacht [the Night of Broken Glass, also called the November pogrom] in 1938. Her family decided to send her to her grandmother and grandfather in the south of France, which was at that time a safe place.

Charlotte Salomon, Gouache from Life? Or Theatre? (1940-1942) Museum Amsterdam / Collection of the Jewish Museum Amsterdam. © Charlotte Salomon Foundation

Charlotte made a painting for of her mother’s suicide, because of course she made this work at the end, after she had figured all this out. There is a panel of Charlotte trying to wait for her mother to come to her bedside, and it says she rose 10 times a night to see if the angelic traces had arrived at the window, but that she is very disappointed. She speaks in the third person about this little girl who’s waiting for her mother to come. It’s so visceral and so beautiful, the way that she brings life and power to these really traumatic events. Do you know why she became interested in art? Was it the death of her mother?

No. She was drawing before that. She was a very shy girl. Indeed, a lonely girl, very observant, very quiet. And not very communicative. She had a governess in her youth who suggested she and paint or draw, and after some time she gained more confidence about her talent.

She met the singing therapist of her stepmother, Alfred Wolfsohn, called Amadeus Daberlohn in He was called Daberlohn (which means “but for wages”) because he didn’t have any money. He was out of work because the Jews couldn’t have normal work. They could work for other Jews, so he was doing singing lessons with Paula. Charlotte met him and he said she was a talented girl and he believed in her talent. That also motivated her to work more with art and to put everything into art. He was her big motivator and he had his own theories about how people who have a trauma had to overcome it and what they had to do with it. Him and his theories are a very big part of her paintings.

There was a relationship between them, we think, as well as a relationship between Paula and Wolfsohn. A lot of possibilities of hearts broken in that house.

Charlotte Salomon, Gouache from Life? Or Theatre? (1940-1942) Museum Amsterdam / Collection of the Jewish Museum Amsterdam. © Charlotte Salomon Foundation

His face is depicted in over 400 of the paintings. His message was the lifeline that someone like Charlotte needed as a young person in Germany. But then she needed it even more when she actually started making this work in France. I want to get to that a bit later, as ends with a letter to him.

But first, let’s speak about the Nazis coming into power and what this really meant. After the pogrom of November 9, 1938, everything changed. Can you speak about what happened to her family and her father immediately after that?

Her father was put out work at hospital. He was immediately taken to Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Paula did a lot of work to get him out and succeeded. He was a broken man when he came out, and this made them decide that they had to flee. That’s why they decided in December 1938 to send Charlotte to the south of France. By the time her stepmother and father wanted to go, it was already almost too late, so they went to the Netherlands into hiding.

Charlotte Salomon, Gouache from Life? Or Theatre? (1940-1942) Museum Amsterdam / Collection of the Jewish Museum Amsterdam. © Charlotte Salomon Foundation.

It must have been a difficult decision to send her off on her own. I mean, wasn’t she only 21?

Yes, she was very young when she leaves on the train. It’s a very stressful scene, and you can see how she painted it. The moment when Daberlohn (or Wolfsohn) comes to the station, the painting becomes light again. It was first very dark, and he comes into the group of people who are waving her goodbye and then the world becomes lighter for her.

You can understand that there is a very big difference between Berlin and the south of France in her paintings. Suddenly all the colors come back and the yellows and the reds. Maybe she didn’t realize that Berlin was very stressful at the time for her. She decided to break her work also in two parts, the one part in Berlin and the other part in France, because there’s a very big difference in color and atmosphere. The only thing was she had to live with her grandparents.

The grandfather was a very stiff man—very old-fashioned from when the days were good for people who were well-to-do. They took it for granted that they were living with this American lady Ottilie Moore for free. They thought it was their privilege to live there. Charlotte couldn’t stand that.

After the suicide of grandmother, Charlotte thought she and her grandfather should leave.

There’s a painting in that depicts the suicide of her grandmother, which Charlotte tried to stop obviously, as anyone would. It is almost the exact same composition as the death of her mother. They had both thrown themselves out of windows. In both of the paintings, the women are depicted in the same position; they look like dead swans. It is just so devastating. But then there is this realization in another painting after these where Charlotte writes, “I will live for them all.” She decided to break this chain of devastation. At the same time, she is left with her grandfather and this became very difficult. How does this evolve in the scenes of

After the death of her grandmother, Charlotte’s paintings become very hastily painted and very sketchy. At that moment, she thought she might go mad. She wanted to overcome this terrible truth. She thought of Wolfsohn, of his theories. Depicting these people in her life, and trying to be in their minds and reconstruct what happened in the family helped her to overcome this big loss for her.

Charlotte Salomon, Gouache from Life? Or Theatre? (1940-1942) Museum Amsterdam / Collection of the Jewish Museum Amsterdam. © Charlotte Salomon Foundation

So the paintings in end and a letter begins. The last few paintings are actually a long letter to Wolfsohn. The last panel of the work, as far as was known until recently, ends with a sentence that is incomplete. It says, “I have to go back to” and it stops. What has emerged in recent years? I know you and your colleagues have brought forth information about pages that went missing. What is in that part of the letter and who removed them?

In 1979, her stepmother Paula Linberg gave Charlotte’s paintings to the Jewish Museum in Amsterdam, years after they had taken it from the south of France in 1947. When it came to the museum, there were plans to make a film about the work. Paula left out some of these pages, a part of this letter. But these pages were seen by the people who made the film. They wrote it down as part of their research. The people who worked on this promised to not tell anybody what was on those pages. There nine pages. After the death of Paula, they decided to open their transcription of those pages. It was heavy for them to do that because they had promised something, but, in the name of art history, you need to open it.

This letter was written to Wolfsohn.

Times were rough and she was having so much support of his theory and she was thinking a lot of him. She told him what kind of things were happening. One thing that happened was that she gave an omelet with poison to her grandfather. He was 82 years old.

In her situation, you can understand how she could do that to him. She was depressed. He didn’t help her a lot. He was only asking for help, but she couldn’t help him. She had to help herself. She wrote in the letter that she used this poison to bring his life to an end. It’s so strange that all the facts you think she painted about her life in … maybe these facts are not true. You don’t know what is real life and what is theater.

To say that she is a murderer is very difficult. It is not very easy to do research on.

This revelation causes a different reading of some of the earlier paintings. There are panels in which she says that her grandfather symbolizes someone that she had to resist more so than Hitler. She says that she would rather spend a night on a train car to a concentration camp than to be alone with him for one night. She says she doesn’t want to share a bed with him, which had to happen at some point because of the lack of amenities. How do you interpret these comments?

It’s very difficult to interpret it. We know so little about the situation. You can only imagine what happened to her. and we don’t know what really was the discussion between them. We don’t know what was meant by the remark of her grandfather to have her join him in the bed. Maybe that’s something that stays in the shadow of the story.

To hear the rest of this interview, tune into the episode on the Art Angle podcast.