When Ilona Katzew arrived at the Los Angeles Museum of Art (Lacma) in 2000 as the museum’s first curator of Latin American art, she noticed a gaping hole in the collection. “I saw that we had a pre-Columbian collection, and this collection of modern Mexican art, but there’s was a whole swath in between that was missing,” she says. The missing piece was the art of Latin America under Spanish colonial rule, also referred to as the viceregal period. “I’m given this responsibility to sort this collection out and to deaccession works that were redundant,” she says of her mandate when she joined.

Two decades later, a new exhibition at Lacma shows how busy she has been. Archive of the World: Art and Imagination in Spanish America, 1500-1800 (until 30 October) features around 90 artworks, objects and furnishings that detail a rich and surprisingly diverse, if contested, era. They reflect new hybrids as European culture mixed with Asian, African and Indigenous cultures. Twenty of the works are new acquisitions and on display at the museum for the first time. The exhibition, writes museum director Michael Govan in the accompanying catalogue, reflects “our long-standing commitment to the art of Latin America. Our dedication to this area embodies our steadfast belief in the artistic and historical sophistication of the material, as well as the importance of providing visitors with greater opportunities to view and study these works as part of global art history”.

Unidentified sculptor and polychromer, Saint Michael Vanquishing the Devil (San Miguel triunfante sobre el demonio), Guatemala, second half of the 18th century, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Purchased with funds provided by the Bernard and Edith Lewin Collection of Mexican Art Deaccession Fund © Museum Associates/Lacma

Since 2015, Katzew has shepherded the acquisition of around 100 objects in this area. That may not sound like a lot, but the curator selected carefully, both because of the limited number of quality objects that reach the market and because there is no readily available acquisitions fund at the museum. Generally, new acquisitions are obtained as gifts or with cash donations from patrons or a combination of the two. For these acquisitions there was also another source: many works were purchased with “funds provided by the Bernard and Edith Lewin Collection of Mexican Art Deaccession Fund”, according to the objects list.

During a recent walkthrough, Katzew discussed some highlights of the exhibition. The Catholic church figures prominently in the devotional paintings and objects that fill the first few galleries—not surprising since the church was directly involved in the colonisation process. A showcase in the middle of the first gallery displays one of Lacma’s most prized objects, the 16th-century silver “Hearst Chalice”, one of the few objects already in the collection when Katzew arrived. It was a gift from the newspaperman and insatiable collector William Randolph Hearst.

Unidentified artists, Chalice (Cáliz), Mexico, 1575-78, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of William Randolph Hearst © Museum Associates/ Lacma

“It’s drawing on very deeply rooted ancient traditions to create this new kind of Christian object,” Katzew says. In its form and decoration, the chalice harkens to European models, but this one also features iridescent feathers that form the background of miniature scenes at the base of the vessel. Using feathers was a pre-Columbian practice, the curator points out.

In the next gallery are several casta (caste) paintings. These showed couples—a white Spaniard and his mixed race wife, for instance—and their children. While created to display the exotica of the “New World” and to codify distinctions between races for European audiences, they were also notably sympathetic to interracial families, probably because they were made by local artists.

One 18th century painting on a scroll, From Spaniard and Morisca, Albino Girl (1763), is by Miguel Cabrera and was famously discovered rolled up beneath a sofa in a Bay Area home, and eventually obtained by Lacma. This is a genre of painting Katzew has long been interested in, and Cabrera is probably its most accomplished practitioner. The man wears the uniform of a Spanish soldier, a cigarette between his lips. He’s seated with a pistol displayed prominently by his leg, while the woman stands before him, and wears a woven shawl and a calico skirt printed with an indigenous flower pattern. In between they lovingly hold their albino child, looking very blonde and rosy.

Miguel Cabrera, From Spaniard and Morisca, Albino Girl (De español y morisca, albina), 1763, purchased with funds provided by Kelvin Davis in honour of the museum’s 50th anniversary and partial gift of Christina Jones Janssen in honour of the Gregory and Harriet Jones Family © Museum Associates/Lacma

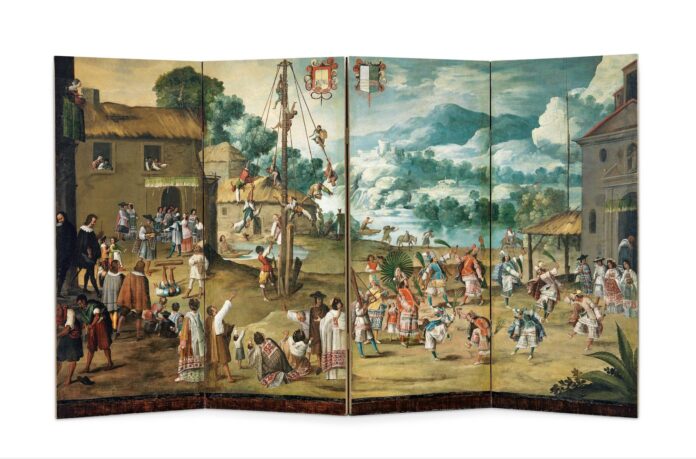

Nearby is the first object Katzew acquired for Lacma, which is also one of the most significant objects in the show, a 17th-century folding screen from Mexico depicting an Indigenous wedding. At right the bride and groom leave the church, while local celebrations take place in the middle—including the mitote, or Moteuczoma dance, and the palo volador, where men “fly” around a pole, their feet tied to the top, a ritual practiced to this day.

“So you have the folding screen, which is an Asian format,” says Katzew, “you have the [painting] style which is very Western, and then you have an Indigenous wedding with all these different games or performances.” Meanwhile, Spanish guests in European dress are gathered at the bride’s house on the far left panel. “I love this object because you really have the whole world in it.”

Asked if she will be adding more objects to the collection, Katzew quickly replies, “Yes, if I can. Always more.”

- Archive of the World: Art and Imagination in Spanish America, 1500-1800, until 30 October, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles.