Vincent Van Gogh’s drawings attract huge crowds. Even the little-known works of the famous Dutch artist are also expensive.

Emily Gordenker, director of the Van Gogh Museum says that since art critics carefully catalog the Van Gogh drawings, it is quite rare that new work is credited to him.

So when a Dutch family approached the museum and asked staff to look at the unsigned art drawing, it was a big surprise that this sketch was a clearly identifiable work by Van Gogh, senior researcher Teyo Minendorp told Reuters. The scientist who led the work to validate the work published his findings in the October issue of Burlington magazine.

Now, as reported by Mike Corder for the Associated Press (AP), the art drawing is on display at the Amsterdam Museum, where it is being shown publicly for the first time.

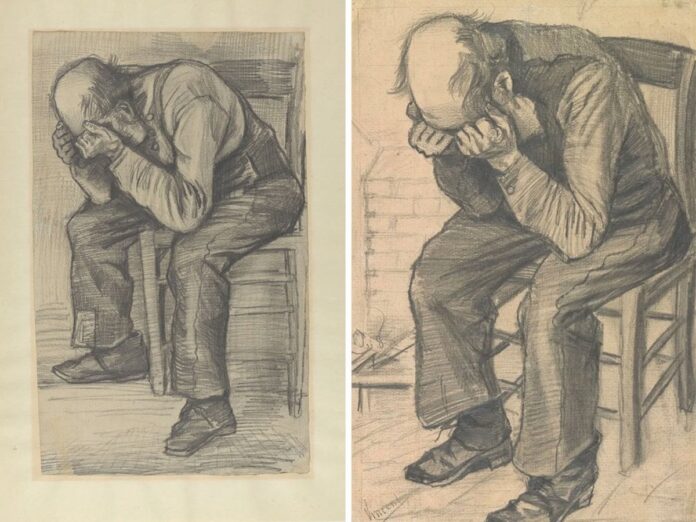

A preparatory dark art sketch for a large 1882 drawing “Worn,” recently referred to work, depicts an elderly man in a shabby suit, hunched over on a chair with his head in his arms.

Van Gogh used a carpenter’s pencil to draw the scene on a 19-by-12-inch ream of watercolor paper. He finished off the lighter parts of the composition by rubbing the bread cakes on a rough surface and then applied a milk/water fixative to better accentuate the dark pencil strokes, reports Mark Brown for the Guardian.

Experts dated Van Gogh’s early work with extraordinary precision to the end of November 1882, when Van Gogh detailed the development of Worn Out in letters to his brother Theo and fellow artist Anton van Rappard.

The Impressionist was “clearly proud” of the composition and just a few days later did a lithograph of the scene, notes Art Newspaper’s Martin Bailey. “Today and yesterday I drew two figures of an old man kneeling with his elbows and clasping his head in his hands,” Van Gogh wrote to his brother in 1882. “… Perhaps I will make a lithograph. What a beautiful sight the old worker makes in his patched suit from the bomb shelter and with his bald head.”

According to Art Newspaper, the artist intended to use Worn Out and other works with English titles to find work in the UK edition, but he either failed to implement this idea or his work was rejected.

Thanks to a newly discovered art drawing that has been kept in a private collection in the Netherlands since about 1910, viewers can trace how Van Gogh’s composition evolved from an initial sketch to its final lithographic form. This fact alone makes the piece “stunning” in Van Gogh’s work, says Minendorp in an interview with Art Newspaper.

At the end of 1882, Van Gogh was only 29 years old. He lived in The Hague with Claesine Maria “Sien” Hornik, a pregnant sex worker who was previously homeless. (The artist was not the child’s father.) She modeled a series of art drawings, including the lithograph “Sorrow” (1882).

That was the early stage in his career. And the artist could hire only poor models, offering maybe 10 cents and some coffee as compensation. For Worn Out, the artist used one of his favorite models, an elderly man named Adrianus Jacobus Seiderland, who boasted characteristic sideburns (and is featured in at least 40 of Van Gogh’s sketches from that period).

Van Gogh pursued an extremely productive creative career, although he remained largely unrecognized during his lifetime. After years of reckoning from severe mental illness, the artist died in poverty in 1890 at the age of 37, possibly committing suicide.

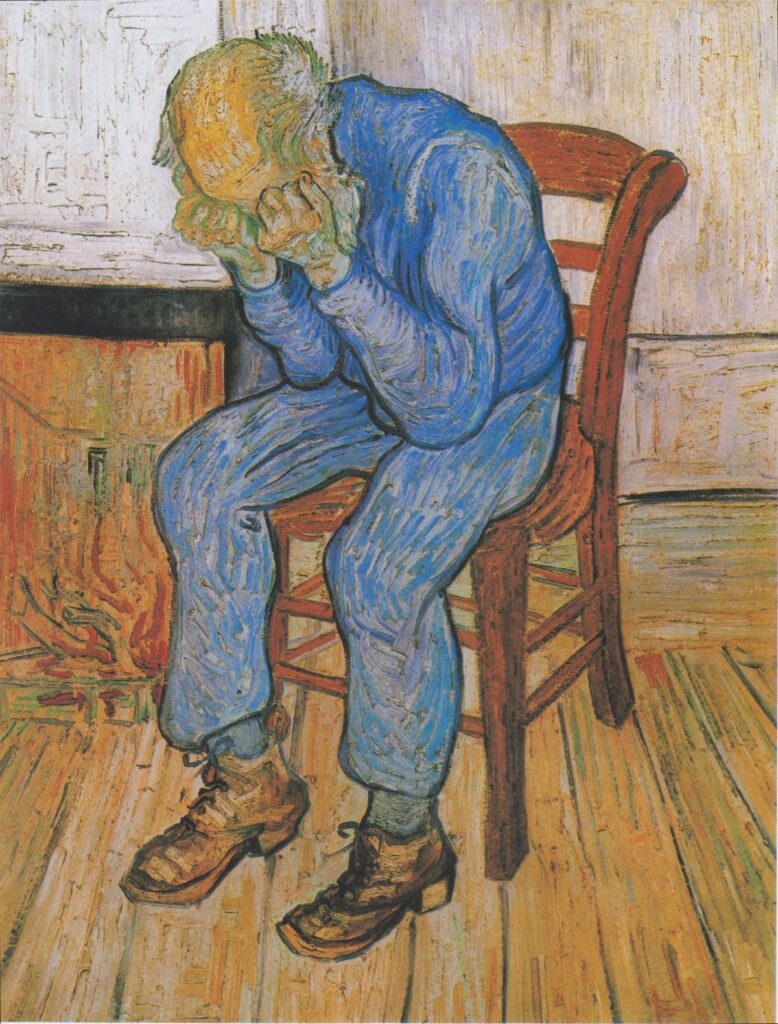

Living in an orphanage near Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, France, the artist used his old lithograph as the basis for a new painting: At the Gates of Eternity (1890). Here, the old man’s costume is in pale blue, contrasting with his tufts of gray hair and the crackling orange fire next to his chair.

The Impressionist has long filled this scene with existential meaning, so perhaps he chose it to paint during a time of great grief and uncertainty. Eight years earlier, Van Gogh had been thinking younger in letters to Theo about the symbolism of his subject:

It seems to me that one of the strongest pieces of evidence for the existence of “something on high,” … namely in the existence of a God and eternity, is the unutterably moving quality that there can be in the expression of an old man like that … as he sits so quietly in the corner of his hearth.