Sometime in the late 1990s, the Luxembourgish painter Michel Majerus was leaving a wedding on Long Island when he convinced his trip partner, art dealer Tim Neuger, to take a detour. The artist was set on seeing the barn where Jackson Pollock painted in the town of East Hampton.

But when the two Europeans arrived, the Pollock-Krasner House was closed, Neuger recalled.

Majerus would not be denied. “People who want things know how to jump fences,” he said, and over the barrier they went. On the property, the artist stood atop Neuger’s shoulders to reach an upper window where he filmed the barn with a handheld camera.

Curiously, this story—decades old now—is where Neuger began when asked about “Michel Majerus 2022,” a series of exhibitions mounted across Germany this month honoring the 20th anniversary of the artist’s untimely death in a plane crash at age 35. Then again, the anecdote makes sense as an entry point into the artist’s world: Majerus had an unrivaled appetite for art history—and he was not afraid to break some rules to feed his hunger, constantly nodding to, or outright stealing from, the icons that came before him.

Michel Majerus, Ohne Titel (1993). © Michel Majerus Estate, 2022.

Photo: Jens Ziehe, Berlin.

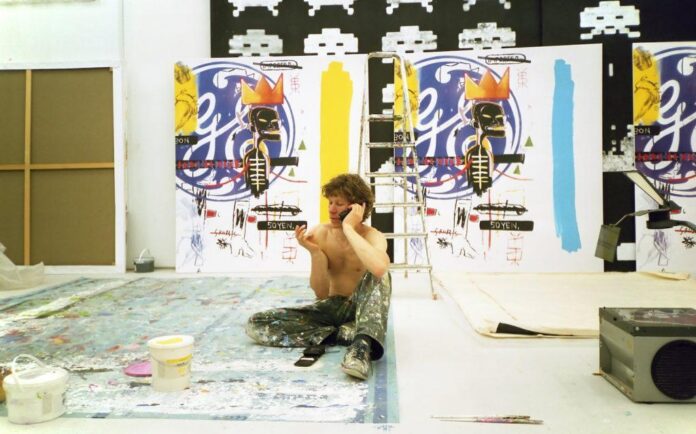

Indeed, everywhere in Majerus’s paintings are art historical allusions that have been swallowed, metabolized, and spit back up along with all the other visual information we can’t help but consume on a day-to-day basis. In this artist’s world, cartoons and corporate logos mingle with homages to Willem de Kooning and Sigmar Polke; a Nike high-top leaps out of a canvas that looks like it was painted by Frank Stella. For one of his best-known bodies of work, Majerus reimagined the much-maligned collaborative canvases made by Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol, with the former’s signature crowned skeleton superimposed over the latter’s General Electric logo.

Majerus is a quintessential postmodernist in that way: hyperaware of the folly of being a painter at the dawn of a new century—countless movements, eras, and isms at his back, all flattened by the internet. But it’s not just from a place of existential anxiety that he operated; a boundless enthusiasm also pervaded his work.

“I once asked [Majerus’s gallerist and Neuger’s partner] Burkhard Riemschneider, ‘What was Majerus like? Was it hard for him to make work?’” artist Cory Arcangel explained in a recent interview. (Arcangel is one of many modern-day artists working in Majerus’s shadow; Jordan Wolfson and Wade Guyton also come mind.) “Burkhard said Majerus was like a faucet. If he had a show, he would just chill out—he was never belabored, or tense—until he knew he needed to do something. Then he would turn on this faucet and the works would just come out.”

Some 19 German art venues, including the KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Museum Ludwig, and Neuger’s Berlin-based gallery, Neugerriemschneider, are showcasing Majerus’s work as part of the survey. It’s an assembly of events unlike any other, and one that posits Majerus as a key late 20th-century figure who bridged generations and foresaw painting’s future in part by looking to the past.

In other words, the sprawling tribute makes the case that Majerus, whose career lasted less than a decade, was one of the most important artists of his generation. If his name isn’t as recognizable as those credentials suggest, well, it’s about to be.

Michel Majerus, 1996. © Albrecht Fuchs, Cologne, 2022. Courtesy of the Michel Majerus Estate

and Neugerriemschneider, Berlin.

Born in Esch-sur-Alzette, Luxembourg, in 1967, Majerus went on to study at the Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Stuttgart, graduating in 1992. His first exhibition at Neugerriemschneider came the year the gallery opened in 1994, and even then bore the everything-but-the-kitchen-sink signature by which his work would come to be defined. A Neo-Expressionist canvas filled one wall, while a Pop-inflected, site-specific mural covered another. The floor featured a reproduced stretch of paved road outside the building.

At first blush, the single-room gallery looked as if it had been designed not by one artist, but several: Gerhard Richter, say; Roy Lichtenstein, definitely; even Looney Tunes animator Chuck Jones. (Neugerriemschneider has recreated Majerus’s 1994 presentation for its contribution to the anniversary celebration this month.)

It was at that exhibition that curator Peter Pakesch first encountered the then-27-year-old artist’s work for the first time. He called the show “legendary.”

“I was stunned and bought one of the paintings right away,” Pakesch said. The next day the two arranged a studio visit, and from there a friendship—one that would last until the artist’s passing—was born. “Being an ardent defender of painting, his approach showed me how painting could also be possible in the upcoming digital age,” Pakesch, who has since curated Majerus’s work on numerous occasions, explained.

Installation view of “kosuth majerus sonderborg,” Michel Majerus Estate, Berlin, 2022. © Joseph Kosuth/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022; © Michel Majerus, 2022. Courtesy of Neugerriemscheider, Berlin, and Matthew Marks Gallery. © K.R.H. Sonderborg, Galerie Maulberger, München 2022. Courtesy of Samlung Grässlin, St.

Georgen. Photo: Marjorie Brunet Plaza.

For the anniversary celebration, Pakesch teamed up with the Majerus estate for a show that juxtaposes the artist’s work with that of his two most influential teachers at Stuttgart Art Academy: the pioneering conceptualist Joseph Kosuth, and the now-deceased abstract painter K.R.H. Sonderborg. Those two titans—one a skeptical theoretician, the other a painter’s painter—represent competing 20th-century impulses; and yet, it’s not hard to spot the DNA of both in Majerus’s own creative genius, Pakesch pointed out.

“Majerus [knew how] to deal, in a very intelligent way, with the major protagonists of recent art history,” the curator continued. “He understood the tensions between different approaches and understood [how] to find surprising ways of synthesizing some contradictions of modernism.”

And perhaps most importantly, Pakesch added, Majerus filtered these tensions through the “new language of the digital,” employing image-editing software and newfangled printing techniques, and painting on nontraditional materials like aluminum and synthetic fabric. Majerus, said Pakesch, “was able to take up the advantages of a special historical moment in a way that very few other artists were able to.”

Fellow curator Daniel Birnbaum identified this knack as well, writing in 2006 that “Majerus’s production of images and visual environments…represents one of very few recent approaches to painting that cannot be understood in terms of a return to anything from the past. His art had a specific kind of newness—not the lofty, if contested, ‘originality of the avant-garde,’ but the prepackaged newness of the latest cell phone graphic or just-released sneaker from Nike.”

The curator’s argument brings to mind the giant, painted skateboard ramp Majerus installed outside the Kunstmuseum Stuttgart in 2002. Covering the functional object were various koan-like captions of unknown origin—“burned out,” “f*ck the intention of the artist”—all styled as if taken from a t-shirt or branding campaign.

“Majerus’s art,” Birnbaum concluded, “was about this newness.”

Michel Majerus, 10 bears masturbating in 10 boxes (1992). © Michel Majerus Estate, 2022. Courtesy of Neugerriemschneider, Berlin, and Matthew Marks Gallery. Photo: Jens Ziehe, Berlin.

The fact that Majerus’s death came by way of a freak accident—a cruel statistical anomaly—throws his achievements into sharper relief. In November 2002, the artist was killed when his Berlin flight bound for Luxembourg City crashed.

Since then, his work has been the subject of major posthumous exhibitions at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin, Tate Liverpool in the U.K., and Kunsthaus Graz in Austria, among others. And yet, the institutional interest has never really extended beyond Europe—until now.

This week, the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami (ICA Miami) opened “Michel Majerus: Progressive Aesthetics,” a survey of the artist’s brief but prolific output from 1991 to 2001. It’s the first of its kind ever mounted by a U.S. museum.

“That’s why we really wanted to do the show,” said ICA curator Stephanie Seidel, who co-organized the presentation with the institution’s artistic director, Alex Gartenfeld. “[Majerus] deserves to be more well-known here.”

Michel Majerus, NET II DIE CAST (2001). © Michel Majerus Estate, 2022. Courtesy of the Collection of Charles Asprey, London, and Neugerriemschneider, Berlin. Photo: Jens Ziehe.

The ICA show arrives just in time for Art Basel Miami Beach, where Majerus’s paintings will also be on view as part of Neugerriemschneider’s booth. But it also comes—and perhaps not coincidentally so—amid the emergence of a larger, market-driven trend coalescing around the artist’s work. Eight of Majerus’s top 10 auction sales have occurred in the last two years, according to Artnet’s Price Database. At the top of that list is his 1999 painting, o.T. (collaboration Nr. 8), which went for $795,000—more than double its presale estimate—at Sotheby’s Singapore in August of this year.

When asked about the increasing secondary prices for Majerus’s work, Neuger responded, somewhat surprisingly, “Don’t believe the hype.” Given Majerus’s early death, the dealer noted that he and Riemschneider have had “a lot of time to create a market. The slower you go and the more precisely you work, the better in the end.”

“It’s about quality, it’s about context,” Neuger added, a point that conjures the image of Mujerus standing atop the gallerist’s shoulders. “It’s not about the money, it’s not about the auction records; it’s about where the artist will stand in the long run.”