In the days since writer Greg Tate joined his ancestors, there has been a lot of talk about how he engaged in music with incomparable style and brilliance as a critic, band leader, activist and producer. But Tate also transformed the global-n-galactic landscape of visual art and film. He did this through his revolutionary scholarship, lectures, performances and curator, bringing the exuberance, politics and poetics of the black radical tradition.

During his tenure in Village Voice beginning in the early 1980s, Tate signaled and catalyzed tidal shifts in cultural criticism toward the interdisciplinary scholarship we read and need today. As the successor to the black arts movement (1965-75), Tate forced the suffocating – and predominantly white and rich – fields of art history and mainstream art media to fight the rebellion and mentality of new areas of black art and ethnic studies. , as well as postcolonial studies on women, gender, and sexuality. He easily switched between black American vernacular and French structuralist theory with the fineness of a rotating keyboard on units and twos. In line with the emergence of cultural studies abroad in Britain, Tate belonged to a new intelligentsia of black art that, like hip-hop culture, began to flourish in narrow communities only to expand to global importance.

Drawing rhetorical strategies from his avant-garde heroes such as Miles Davis, his approach to writing and curating mirror jazz improvisation, black rock focused on rhythm and free style in hip hop. In 1992, the year he published his basic collection Flyboy in the Buttermilk, he said in an interview with NPR, “I have always tried to produce critical writing that has as much vitality and viscerality as an art or phenomenon or experience that I have tried to describe to someone else. I’m really trying to include the reader in my central nervous system in its most demanding state. “

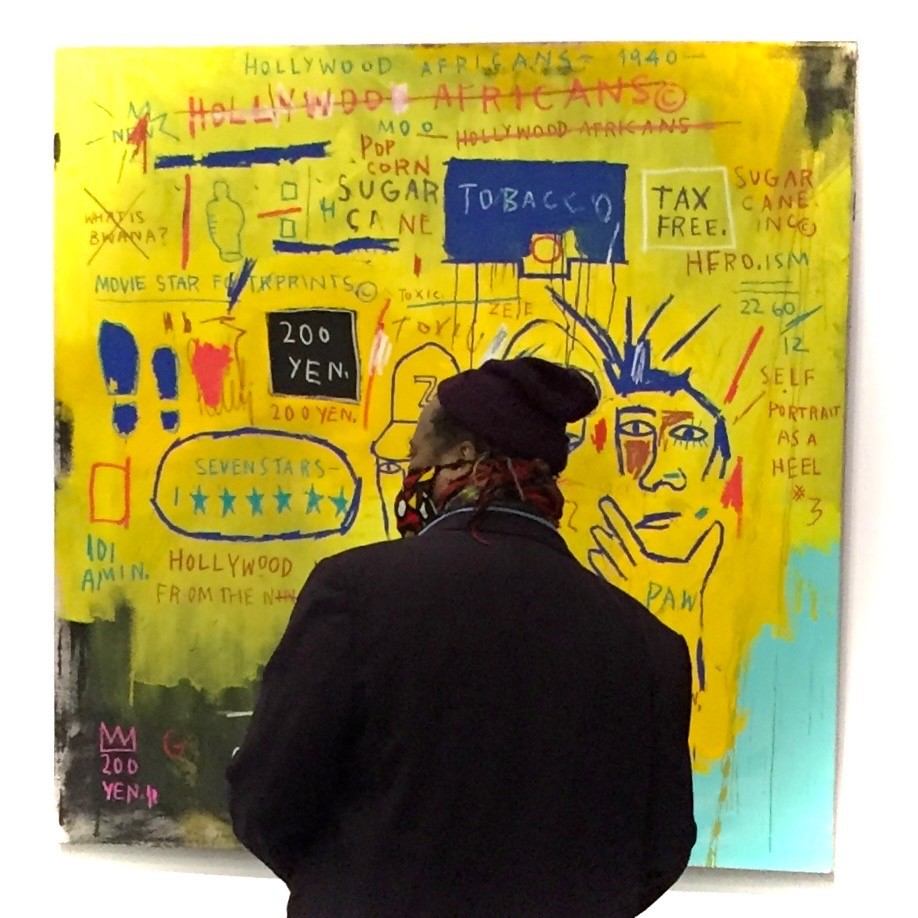

Tate challenged the principles of art writing and cultural criticism by focusing on the lived experience of a work of art, looking at it through the lens of black genealogies and epistemologies. In doing so, he restituted the work, placing it in an appropriate cultural, social and political context. His early writings on black visual art – especially Jean-Michel Basquiat, Rammellzee (1985), David Hammons, Senga Nengudi, Romare Bearden (appearing in his key 1986 essay “Cult-Nat Meet Freaky-Deke”) – not only hinted at by the Acceptance or by the institutions of white art by black art, they actively created an opening through their insistence on a sophisticated line of black art and futuristic projections.

In the title essay in Flyboy in buttermilk, “Flyboy in the Buttermilk: Nobody Loves a Brilliant Child”, Tate pointed out how and why museums and the art world failed to recognize the genius of the Basque Country in his time: from the world of ‘serious’ visual art. To this day, it has remained a bastion of white supremacy, a beacon of the rich, whose high-walled barricades suit only Wall Street and the White House and whose practice of exclusion is carried out 24-7-365. It is easier for a rich white man to enter the kingdom of heaven than for a black abstract and / or conceptual artist to get a solo performance in lower Manhattan or a contribution to the pages Artforum, Art in America, or The Village Voice. The prospect of such an artist becoming a bona fide world celebrity (and no less at the beginning of her career) was, until the arrival of Jean Michel Basquiat, something of a joke. ”

“No area of modern intellectual life has been more resilient to recognizing and endorsing people in color than the world of‘ serious ’visual art,” Tate wrote in the early 1990s.

Tate waged a war of words and himself tore down some of those barricades. Until 1992, he was one of several black art critics commissioned by the Grand Museum to write an exhibition catalog, now contributing to the key essay “Black as B”. for the retrospective publication Whitney’s Basquiat. Not long after, in some cases, many local newspapers and alt-weeklies collapsed. Journalism as a sustainable form of putting dinner on the table has failed, even when the art market has jumped sharply. Greg began teaching black art, visual culture, and music at Brown, Columbia, and other universities, and contributed to numerous exhibition catalogs, consolidating his role as a regular in the discourse of contemporary art. A self-proclaimed “wandering scientist”, he has lectured and written for museums such as the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum, ICA Boston, ICA London, the Houston Museum of Contemporary Art, Tate and the Harlem Study Museum, as well as galleries such as Gagosian and Deitch Projects.

Tate could make out the urgent messages among the cacophony and forced us to be present in it. Just as he affirmed that hip-hop makes history, while others insisted it was a passing fad, he consistently affirmed that visual artists define their moment. He raised creators as urgently as they created work. To quote Basquiat quoting Charlie Parker, “Now is the time.”

Back in 1989, emerging from the declining wave of post-graffiti art and Basquiat’s tragic death, Tate had the foresight to link graffiti art to a visual revolution that took over not only New York City’s landscape but the world of pop culture and art that drank from it. He wrote, again in “Flyboy in the Buttermilk”: “Let’s go back to postpunk lower Manhattan, no-wave New York, where loft jazz, white noise and black funk community are currently desegregated from the Downtown rock scene and hip-hop. Cults of graffiti are drawn into the station, printing trains carrying the return of representation, figuration, expressionism, pop artistry, investing in canvas painting and masterpiece ideas. Whether the writers hinted at or inspired market forces to all this fetishism of art and anti-conceptual material, the question is still open. ”

As museums continued to neglect these revolutionary artists 40 years later, Tate’s question became the driving force behind the research behind the exhibition “Writing the Future: Basquiat and the Hip-Hop Generation” 2020-2021, which he co-curated at the Museum of Fine. Arts, Boston. Through its portable exhibition design, multimedia installations and electrical artwork, the show aimed to reach the highest notes in Tate’s writing, involving you in New York’s nervous system in the 1980s.

As a fearless maestro for the Burnt Sugar Chamber Orchestra, Tate has marched through many museums with his cacophony parade, including the Brooklyn Museum, Kitchen, Hammer Museum, Hallways Contemporary Arts Center, Walker Art Center, and more, as well as institutions such as Lincoln Center and Apollo Theater. Relying on the performance strategies of Butch Morris’ conductor, Tate proved to be the maestro and radio conductor of Burnt Sugar, interpolating his passions from visual art, pulp film, speculative fiction and, of course, funk. In addition to Tate’s immediate family, we express our condolences to all his selected tribes, especially the Black Rock Coalition and Burnt Sugar, with whom he shared a lifetime of radical creative collaboration. Although the band’s membership is notoriously ongoing, according to the current website, the staff includes: Jeremiah Abiah, Rene Akan, Marc Cary, Honeychild Coleman, Pete Cosey, Morgan Michael Craft, Latasha Nevada Diggs, Justice Dilla-X, Captain Kirk Douglas, Melvin Gibbs, Carl Hancock-Rux, Trevor Holder, Satch Hoyt, Julia Kent, Vijay Iyer, Tia Nicole Leak, Okkyung Lee, Derrin “D Max” Maxwell, Omega Moon, DJ Mutamassik, Qasim Naqvi, W-Myles Reilly, Matana Roberts , Petre Radu Scafaru, Shariff Simmons, Swiss Chris, Somi, Tamar-kali, Imani Uzuri, Michael Veal, Christina Wheeler and Nioka Workman to name a few. And Sugar Lifers: Jared Michael Nickerson, Lisala Beatty, Lewis “Flip” Barnes, Bruce Mack, Micah Gaugh and Jason DiMatteo with current Righteous Jumpsuit team Shelley Nicole, Mikel Banks, Abby Dobson, Julie Brown, JS Williams, V. Jeffrey Smith, LaFrae Sci, Avram Fefer, “Moist” Paula Henderson, Dave “Smoota” Smith, Mazz Swift, Leon Gruenbaum, Andre Lassalle, Ben Tyree, Greg Gonzalez, Chris Eddleton and Vernon Reid.

At the time of his death, Tate was completing his magnum opus, decades-long quest and sequel to “Cult-Nats Meet Freaky-Deke”. A key articulator of Afro-Futurist thought, he could gently land the Mother Ship on this planet and launch it back to Saturn through its multimedia magic. Tate got such a scam out of being on the front lines with artists like George Clinton and Rammellzee. In 1985, Rammellzee told Tate in an interview: “We are advanced in terms of science and technology, but the attitude of the population and the control of the population is still Gothic. We still don’t know what we’re doing. We still don’t know how to leave this planet the right way. “

Tate’s ascent to the stars may not feel right for a long time to come, but his writings and recordings remain with us. His raw material was the whole of America fighting its own self-created terror and black genius and creativity that illuminate the paths to survival and dreams of freedom. Aligning his austerity with love, Tate connected us haunted compatriots with humanism and the cosmos, reminding us of our common characteristics. Tate shared his beautiful mind and huge heart with anyone who fixed his eyes and ears on his page, his stage and his gallery – not a cube but a circle, which continues to expand.