Baseera Khan: I Am an Archive is presented as part of the UOVO Prize for an emerging Brooklyn artist. Baseera Khan uses their own body as an archive, often employing a variety of multimedia collage techniques to visualize the lived experiences of people at the intersections of Muslim and American identities, both today and throughout history. The exhibition debuts eleven new artworks, in conversation with key works made since 2017, that explore Khan’s body as a site of accumulations of experiences, histories, and traumas.

On view are rich and multilayered sculptures, installations, collages, drawings, photographs, textiles, and a video in which Khan investigates othering, surveillance, cultural exploitation, anti-blackness, and xenophobia within our public and private spaces—and proposes avenues for protection and liberation. The works express Khan’s interest in revealing the economics of goods and materials—such as oil, hair, architecture, and art—as commodities that create inequalities and otherness and that are historical and contemporary drivers of global change.

Khan is the recipient of the second UOVO Prize, which recognizes the work of emerging Brooklyn artists. As part of the prize, they receive a solo exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, a commission for a 50×50-foot art installation on the façade of UOVO’s Brooklyn facility, and a $25,000 unrestricted cash grant. The mural is currently on view.

Baseera Khan: I Am an Archive is curated by Carmen Hermo, Associate Curator, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Brooklyn Museum.

The UOVO Prize is made possible by Major support for this exhibition is provided by the Brooklyn Museum’s Contemporary Art Committee.

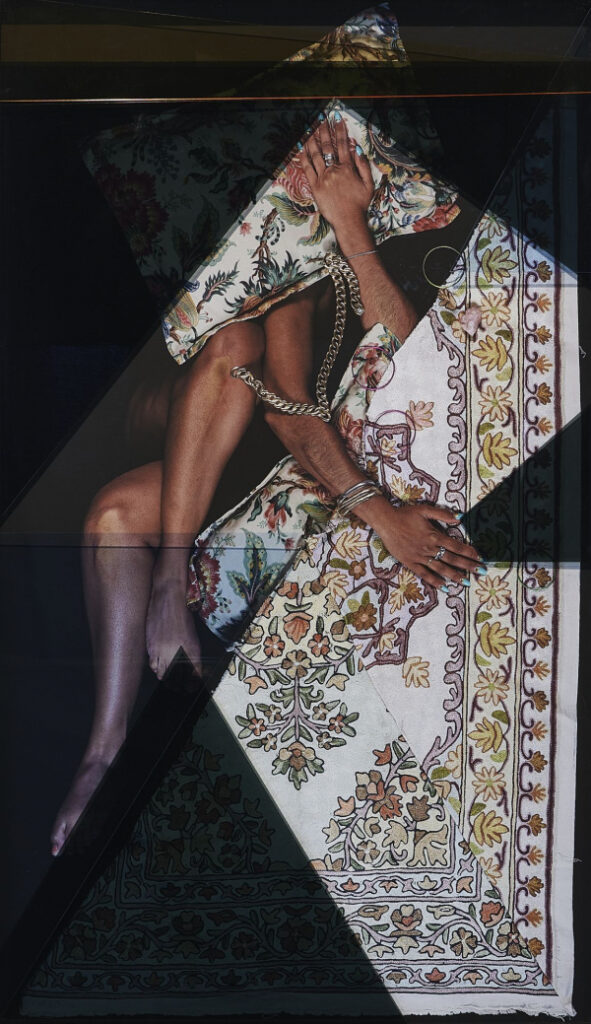

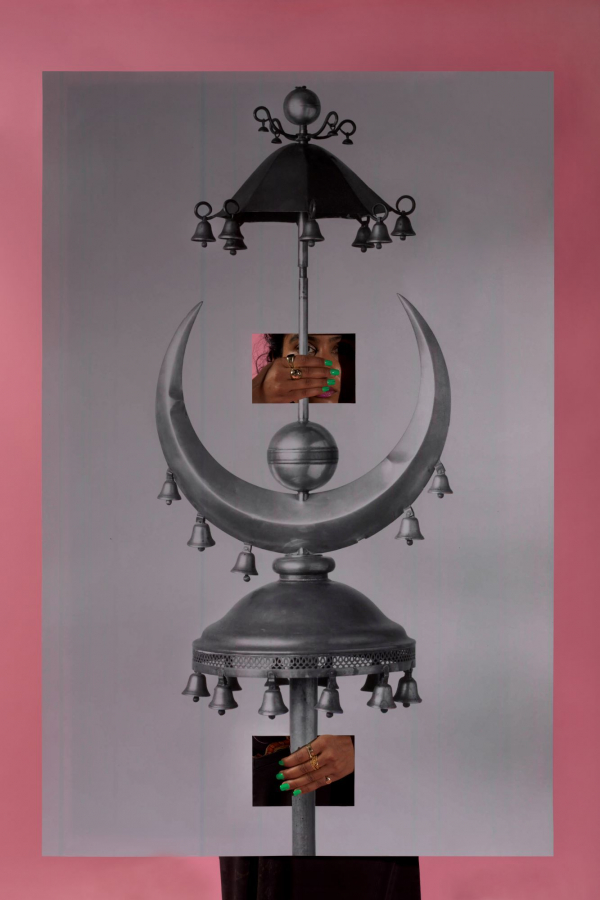

Subtle and alluring, a brown eye gazes out from behind the mihrab motif at the center of a prayer rug. The gaze pierces the two-dimensional surface, revealing that this work, which has the appearance of a photograph, is actually a collage of images used to partially conceal the body of artist Baseera Khan. In this work, one in a series titled “Law of Antiquities” (2021–), Khan’s images digitally merge the artist’s figure with rare and fragile artifacts from the Brooklyn Museum’s Arts of the Islamic World collection, constructing scenes in which they seem to interact. Mosque Lamp and Prayer Carpet Green from Law of Antiquities (2021) features that richly colored seventeenth-century Iranian prayer rug floating in the foreground. The textile was photographed against a stark white background that contrasts with the draping chroma-key backdrop of the overall image and the deep red of the artist’s shoes. Khan digitally cut out and slightly shifted the rug’s intricate mihrab, allowing it to suggest a niche, much like the architectural feature that inspired the motif. Several sets of hands, some with vibrant green nail polish, grip the rug’s virtually excised core and, in two images within the mihrab, support an ornate glass lamp that once illuminated a mosque. The rug functions as a wall, guarding the artist’s body, and the center cutout as a window, drawing the viewer’s gaze deeper into the mihrab.

Khan’s solo exhibition “I Am an Archive,” curated by Carmen Hermo at the Brooklyn Museum, features more than forty works made since 2017, more than a dozen of them brand new. The pieces explore a range of experiences that come with existing in a brown Muslim body in the United States—including Islamophobia, assimilation, adaptation, and pride. Throughout, Khan positions the body as an essential site of knowledge and cultural retention. Artists and scholars alike have increasingly problematized the archive as a site of power tied to white supremacy and cultural erasure. The titular statement “I am an archive” asserts the artist’s authority over their own history while subtly undermining a Western understanding of canonization. The objects Khan chose to incorporate into this series—often labeled and categorized by nation, religion, and period—contain spiritual and colonial histories, as well as larger migratory, transient, and multicultural ones, that come alive outside the museum context. That these objects reside in the Brooklyn Museum indicates not only that they are part of pervasive stereotypes of orientalism, but also that they belong to transnational histories of power that span antiquity to the present.

Khan explores the intersection of materiality, technology, and identity in their practice. Known as a performance artist, image-maker, and sculptor, they here demonstrate the breadth of their practice and skill, most evidently their expert manipulation of materials. In one of the galleries, a long thick braid of what appears to be human hair hangs from the ceiling and pools on the floor before a large projection that documents Braidrage (2017–), a performance in which Khan created a large-scale drawing using their entire body. The drawing surface resembles a rock-climbing wall, but in place of stone protrusions, Khan has installed casts of their own body parts made from resin, embedded with hair, chains, and remnants of hypothermia blankets, like those often given to refugees. With a rinsing gesture, they cover their bare hands and feet in black charcoal, after the Islamic pre-prayer tradition of Wudu; then the artist climbs the wall and begins to “draw.” A ritualistic act ensues as they climb vertically and horizontally, making prints or sweeping marks with their hands and feet, and then descend only to scale the wall once again. Having confronted their own body, through both the mounted casts and the physical exertion, Khan considers the drawing complete after reaching exhaustion.

At the forefront of the exhibition is its namesake, I Am an Archive, Speaker, from Bust of Canons (2021), a 3D-printed sculpture modeled after Khan’s body in acrylic, resin, and steel, completed with a long ponytail of the artist’s hair. The figure references a white marble Yakshi sculpture (twelfth to thirteenth century) from the museum’s collection in which a goddess’s body is carved in an S-curve pose. Erupting from the figure’s chest, or anahata, is a bulbous speaker playing songs written and performed by the artist. Some twenty melancholy alternative songs permeate the gallery, in which a series of ornate revolving chandeliers hang. Their bright colors reflect light and make patterns on the floor, creating a potential space for gathering, dance, and contemplation. The inclusion of the artist’s hair is personal and significant. In many Muslim cultures the presentation of hair represents one’s expression of spirituality and gender, and is a marker of health and beauty. Hair is also a global currency that can be cut and sold, indicating earning potential and social worth. Throughout the exhibition, hair acts as an alternative archive, containing not only various cultural meanings, but also, more literally, DNA.

This great length of hair is a testament to a particular type of sacrifice, be it to one’s freedom from convention or to the fidelity of the sculpture. A three-dimensional collage, Khan’s sculpture again uses technology to composite an object from the collection and their own body, ultimately enabling us to conceive of hybridized, and arguably more legitimate, archives.