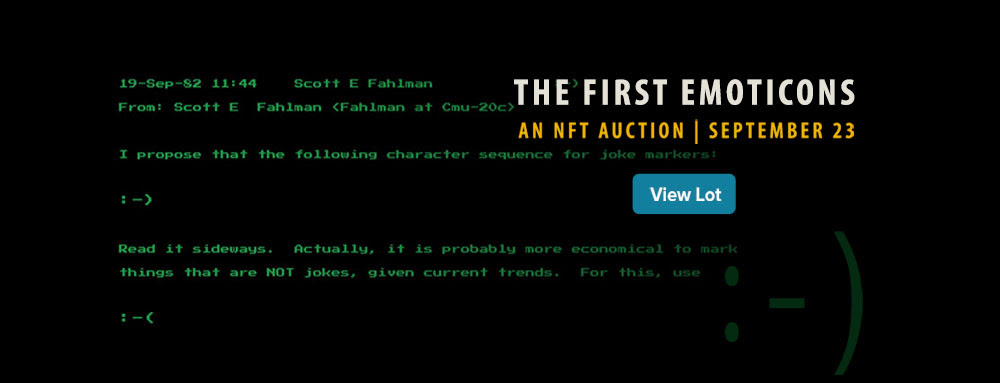

On September 19, 1982, Carnegie Mellon University computer science professor Scott E. Fahlman invented two of the most ubiquitous symbols of recent human history: the smiley-face and frowny-face symbols, : – ) and : – (, known today as “Internet emoticons.” An emoticon is an easy-to-type pictorial representation of facial features using only the characters on a standard keyboard. Fahlman’s message proposed the use of the : – ) symbol as a “joke marker,” meaning “I’m only kidding”, and the : – ( to mean “I’m serious.” These symbols soon acquired the additional meanings of “I’m happy” and “I’m unhappy.”

The idea was to avoid some of the online arguments (“flame wars”) that would frequently break out on this new medium where people could not make use of body language or tone of voice to indicate whether or not a comment was meant as sarcasm or was serious. Fahlman’s creation is significant not only because it brought humanism, context, and emotion to a featureless screen, but also because it represents the first semblance of “meme” and “viral” culture in online discourse. In 1982, when these symbols were proposed, university researchers were just beginning to experiment with the military-run ARPAnet, the precursor of today’s Internet. Local Email was in general use, and could now be sent over the network to other universities and research groups.

Online bulletin-board systems or “bboards” provided a crude, text-only precursor to today’s social networks. Emoticons flourished in these early media, and soon spread to all the other sites on the network. Many additional emoticons were invented over the years, most of them following Fahlman’s original template: some kind of a face, turned sideways.

The ARPAnet was soon turned over to civilian control in the U.S., becoming the Internet. As additional universities joined the Internet community, one by one, they soon were greeted with email from older sites. Some of these messages contained emoticons. So this “meme” spread first though U.S. universities, and then to universities and research groups around the world. Wherever email went, : – ) and : – ( soon followed. In the mid-1990s, when the Internet and the World Wide Web burst into the living rooms of ordinary people, so too did the emoticons, and then (when the technology allowed) their descendants, the graphical emoji. It is estimated that today these symbols, collectively, are used several billion times a day, worldwide.

From an anthropological viewpoint, early pictograms and ideograms have been integral to our understanding of communication within ancient civilizations. We can trace their lineage from Sumerian cuneiform and Egyptian hieroglyphics through emoticons and on to present-day emojis.

The record and exact text of Fahlman’s original message was lost for almost twenty years, but after an “archeological dig” through CMU’s backup tapes, led by Mike Jones and Jeff Baird, Fahlman’s original message and the discussion it was a part of were retrieved on September 10, 2002.

So we now have irrefutable evidence of the emoticon’s first use online and Fahlman’s role as its maker. Moreover, by leveraging the advent of NFTs, digital tokens underpinned by blockchain technology, this unique fragment of history can become the centerpiece of any collection. Traditional historical artifacts, such as the British Museum’s Rosetta Stone, benefit from their existence in the physical world: their rarity and authenticity can be verified tangibly. This was not a possibility for artifacts from the digital world, until recently. As we move further into the digital age, and as human-computer interaction becomes synonymous with modern life, the ability to provide this same authenticity to pieces of digital culture, via the use of NFTs, is a welcome development. Through the minting of unique NFTs, buyers will now have proof-of-ownership and authenticity for their digital artifacts.

The : – ) “smiley” and : – ( “frowny” emoticons not only represent an inflection point in our development of cognitive artifacts but they also represent the first strides towards a new kind of universal language. What started as a light-hearted attempt to inject tone and context into message boards at Carnegie Mellon University has snowballed into one of the most ubiquitous features of contemporary online language, communication, and culture.

As Professor Fahlman notes in his essay that accompanies this digital artifact: “The : – ) emoticon is the distilled, abstract essence of a smile. It has no gender, no race, no age, no religion, no politics… It’s just a smile. This is a big advantage over the emoji versions. With : – ) we don’t have to argue about how many different versions we have to create for different groups. It looks like all of us.”