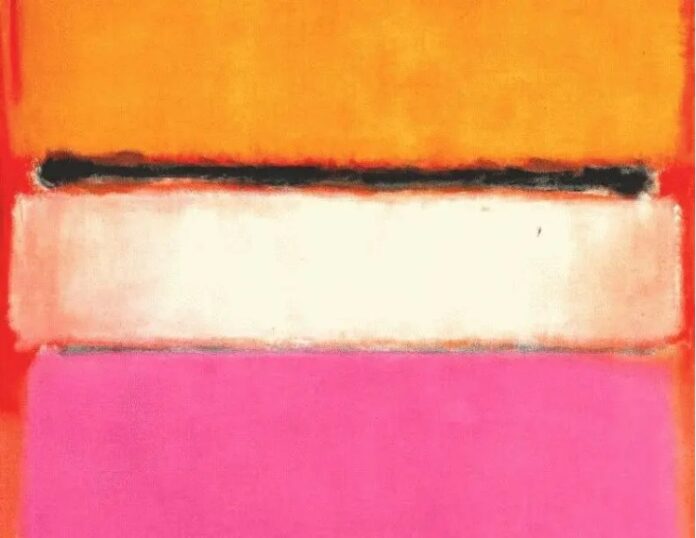

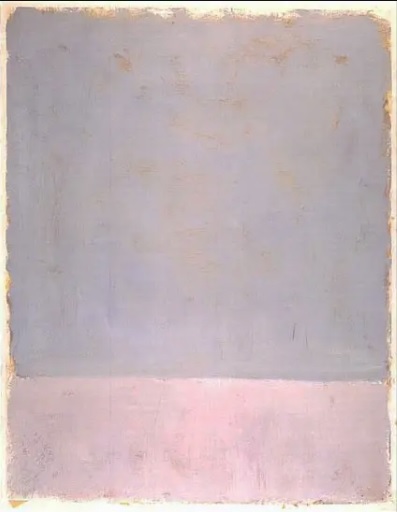

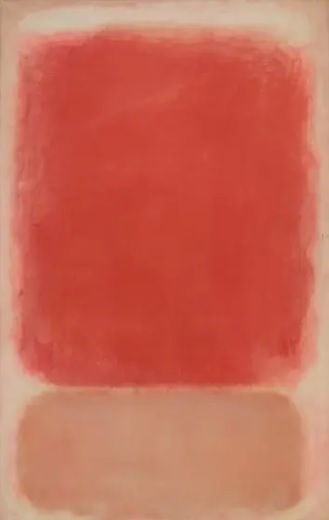

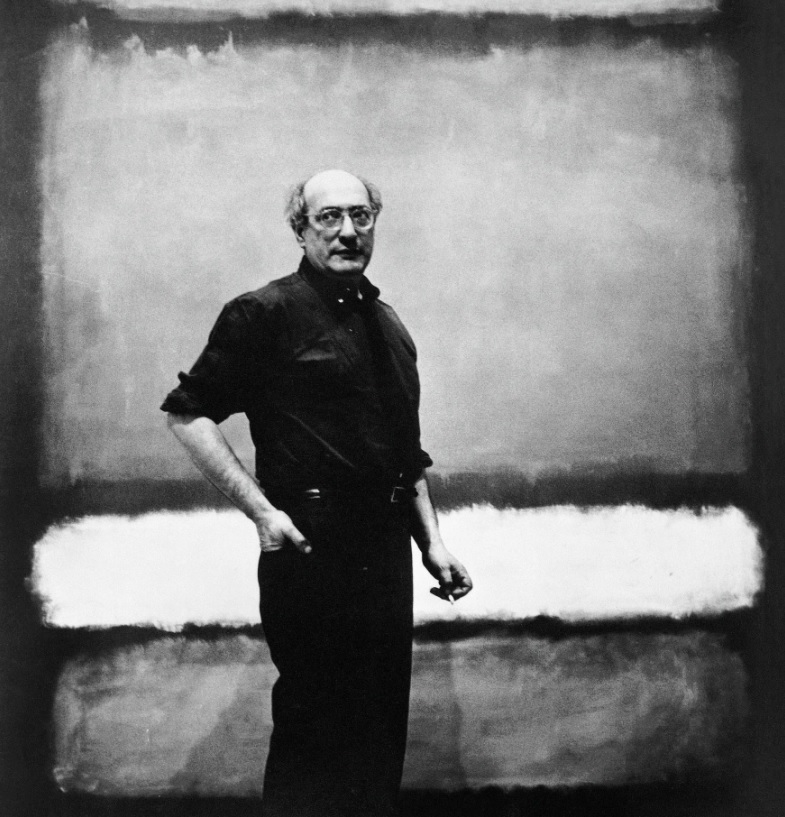

Mark Rothko (1903-1970) was one of the most famous members of the Abstract Expressionist movement, known primarily for his color field paintings. His famous signature large-scale color field paintings, consisting exclusively of large rectangular blocks of soaring, pulsating colors, absorb, connect and transport the viewer into another realm, another dimension, freeing the spirit from the constraints of everyday stress. These paintings often glow from within and seem almost alive, breathing, interacting with the viewer in a silent dialogue, creating a sense of the sacred in the interaction, reminiscent of the I-Thou relationship described by renowned theologian Martin Buber.

About the relationship of his work to the viewer, Rothko said: “The painting lives a camaraderie, expanding and accelerating in the eyes of the sensitive observer. It dies for the same reason. So sending it out into the world is risky. How often it must be disturbed by the eyes of the insensitive and the cruelty of the powerless.” He also said: “I am not interested in the relationship between form and color. The only thing I care about is the expression of basic human emotions: tragedy, ecstasy, destiny.

No matter how much effort the artist made to make the public perceive his paintings solely as the embodiment of pure, unadulterated emotion on canvas, he could not avoid the fact that they fit perfectly into the bright, and sometimes garish, interiors of his time.

Although his rebellious brain was more concerned with ideas and their adequate realization than with whether the viewer would enjoy the paintings aesthetically, Rothko created stunningly beautiful canvases. Whether he wanted to or not, he managed to find combinations of tones valuable in themselves, in their minimalism and purity, without regard to the meaning he put into them.

He was a gifted colorist, although this was not a compliment but an insult to the artist. This is evidenced by an incredible story that seems to have only happened to him.

Mark Rothko was on the list of honored guests invited to President Kennedy’s inauguration in 1961. He was honored, but not until Kennedy’s sister and her husband asked the artist for one of his works to see how it would fit in with the style of their apartment. It was enough for Rothko to cut off all contact with the Kennedy family forever.

And this was not the only case where the artist could not be persuaded to part with his paintings, neither the prestige of a potential client, nor the multi-digit sums in the check. The realization that his paintings were valued by his admirers primarily for their decorative function was extremely painful. So in the second half of the 1950s, Rothko began to deliberately thicken the colors, choosing increasingly darker shades. But it didn’t help much: it was still painfully beautiful.

The Genius is in the Details

Yes, paintings for Rothko were more than just paintings. And in a sense, more than art. He lived them and wanted the viewer to be able to fully immerse himself in the space of his paintings. For the sake of this goal, he made no compromises when it came to their release.

Galleries had to comply with all his requirements. Aisle halls were not suitable for Rothko paintings. The works of other artists and other foreign objects could not be in the gallery: nothing should have prevented the viewer from having direct contact with Rothko’s work. This is why minimum lighting, closed windows, and no frames of any kind – nothing that could shift the focus away from the canvases themselves – were envisioned.

At the peak of his creative prime, Rothko was no longer thinking in terms of individual paintings, his mind was constructing concepts of inseparable art space. He sought to create entire ensembles that would sound in harmony with the vibrations of his experiences. The limit of Rothko’s dreams was to paint canvases conceived for specific rooms, ideally designed by himself – with the wall geometry and placement of natural light sources he needed.

“Each painting lives in the neighborhood with other canvases, serving for it in the eyes of the people a kind of continuation. Left alone, the painting dies. There is therefore nothing more frightening and insensitive on the part of the artist than to exhibit only one of his paintings,” the artist believed.

Rothko’s exquisite art

Long before Rothko started to practice it, painting had begun to break away from its decorative, religious or fleeting moment in life functions. And the more artists try to tell the viewer something rather than show it. In our time, technique, craftsmanship and virtuosity are not in demand, but ideas and meanings.

Rothko freed his paintings from these obligations as well: he was irritated by any interpretations or interpretations of hidden meanings – in this respect he was utterly straightforward. “The tragic experience of catharsis is the only source of any art. My paintings are an unpredictable journey into an unknown world. Most likely, the viewer would prefer not to go there,” he wrote.

It was the viewer who was the main critic and judge for Rothko; his opinion was decisive for him, unlike the verdicts of any authoritative sources. “No commentary can explain painting,” he believed. – All explanations must come from a completed experience of the experience between the painting and its observer. The appreciation of art is truly a marriage of intelligences. And art is also a marriage, and if it is not completed properly, then it is barren.

Despite the fact that today the artist is considered one of the leading representatives of abstract expressionism, he did not identify himself as such. And the more his popularity grew, the more it seemed to him that critics admiring his “abstractions” were missing the point.

“My art is not abstraction. It lives and breathes,” Rothko declared. – I’m not interested in the relationship between color and form or anything like that. I’m only interested in expressing basic human emotions: tragedy, ecstasy, despair and so on. And the fact that many people suddenly lose themselves and burst into sobs in front of my paintings means that I can communicate these basic human emotions.

Rest is a matter of Technique

As in other areas of the arts, recognition is the most valuable thing a talent has in today’s world. There are millions of great voices in the world, but how many of them can we unmistakably identify when we hear them on the radio? The situation is similar with paintings.

If you have seen a selection of Rothko paintings at least once, their image will be firmly imprinted in your mind. And you’re unlikely to confuse them with the works of any other artist (unless they’re his imitators).

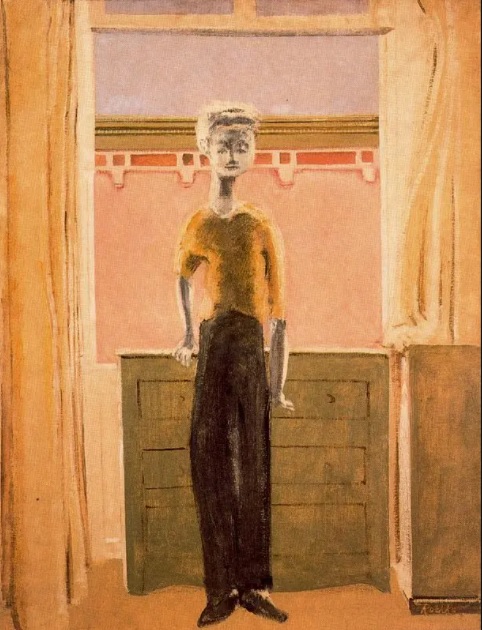

This is what Rothko’s experiments looked like before he invented the signature style.

If only for the mercantile reason that, for reasons of vanity, collectors have historically tended to buy works of art that will declare their author even without a signature in the bottom corner; a unique handwriting is already half of an artist’s success.

Patterns based on motifs from works by Van Gogh, Kandinsky, Mondrian, Dali, Warhol and others are reproduced and replicated in the most unthinkable hypostasis: from interior items to cups, clothing, cake design and even hairstyles.

Rothko also managed to immortalize his name by coming up with an unmistakable formula: versatile rectangles floating in planes of color. But like Malevich’s squares, Rothko’s color fields are not as simple as they seem. The artist used several techniques, the secret of which he hid even from his assistants.

Research with an electron microscope and ultraviolet light revealed that the artist used both natural ingredients like eggs or rabbit skin glue, and artificial substances: acrylic, modified alkyd, phenol-formaldehyde resin, and so on. He needed all this in order to achieve rapid drying of the different layers of paint without mixing them up, so that he could apply new ones over the old ones without hindrance.

The number of such layers in different paintings was up to twenty, and these could be barely different shades – this allowed to achieve the same effect of depth and flicker of color. Rothko also deliberately avoided any frames, both literally and figuratively: he painted over even the sides of the canvases, as if the space of the picture had no borders.

Black Square in a Cube

The culmination of Rothko’s artistic evolution and, in a way, his mausoleum was an iconic structure in Houston, Texas, better known as the Rothko Chapel. His work on a series of panels for the Four Seasons restaurant (which never took their place on the walls of the establishment, because he refused to give his creations to raise the appetite of millionaires) prompted the oil magnates de Menil to offer him to paint canvases for the chapel on the campus of St. Thomas University.

Rothko created 14 large-scale paintings for the chapel, which was originally conceived as a Catholic church but ended up as an ecumenical church for people of all faiths (and equally as an art center). Seven of them are black rectangles almost merging with a rich burgundy background. Another seven canvases are painted in purple, recalling the hues of the night sky in different time and weather conditions.

Rothko worked for three years (1964-1967) on paintings for the chapel, and it was not without intrigue. The terms of the contract allowed the artist to interfere with the layout of the structure, which resulted in a falling out with the first architect who worked on the project. Then he collaborated with the second and the third, but Rothko never lived to see the building finished. Still, thanks to his involvement, the building has an octagonal base and a source of natural light made right in the ceiling.

Rothko’s chapel opened a year after his death, in 1971. And while some visitors look around in bewilderment, asking “where are the paintings, exactly?” others are frozen for a long time in the meditative shimmer of Rothko’s “black holes.

If in the process of working on the panel for the restaurant the artist wished visitors to feel immured forever among the brick walls, here, apparently, he offered the viewer the feeling of maximum closeness to eternity. Either in weightlessness amidst the silence of open space, or in the final resting place when the last nail is hammered into the lid.

As is often the case with the artist’s legacy, Rothko’s chapel has also been a source of inspiration for other artists. Peter Gabriel, for example, wrote the song “14 Black Paintings,” which appeared on his sixth studio album, Us, in 1992.