“It’s just a feeling—it’s just a feeling. It’s like how do you tell somebody what it’s like to be in love? … You cannot do it do save your live. You can describe things, but you can’t tell it, but you know it when it happens. That’s what I mean by freedom.”

So intones Nina Simone in an archival interview when requested to elucidate her 1967 rendition of the track “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free.” Simone’s phrases rang all through the foyer of Chicago’s Smart Museum of Art final evening as a part of a program titled “Art After Dark: Art and Protest” to launch town’s Expo Art Week, timed to the Expo Chicago artwork honest that opens to VIPs on Thursday.

“Art and Protest” provided a musical program of eight Simone songs, together with a dialogue of her music and that of Bob Thompson, who’s at the moment the topic of a touring retrospective on the Smart on view by May 15. The night was organized by the Smart’s lead museum educator, Katherine Davis, who can be a famend Blues musician. She described the night’s program “as a road map from the ’60s to today.”

For many years, Simone has served as a touchstone for generations of artists, together with 4—Rashid Johnson, Julie Mehretu, Adam Pendleton and Ellen Gallagher—who banded collectively to save Simone’s childhood home in 2017. That quartet is at the moment seeking to remodel the home in North Carolina right into a inventive vacation spot.

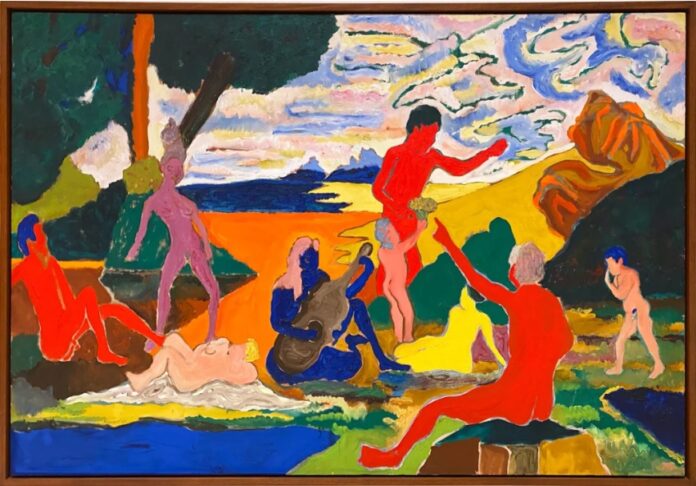

There’s a particular connection between Simone and Thompson, who had been shut buddies and tireless artist-activists in the course of the civil rights period. They used their artwork to think about new prospects for the liberty of Black individuals—and by extension different marginalized teams—on this nation. Thompson even titled a 1965 canvas Homage to Nina Simone, which depicts a colourful bacchanal the place a blue feminine determine, framed by a passage of orange zigzag, sits on the heart holding a brown guitar. Around her are varied different figures enjoyable and vibing to her strumming. Pastel colours swirl within the sky above, whereas hues of inexperienced meld into one another on the backside.

Thompson’s retrospective, which was organized by the Colby College Museum of Art in Maine and can then journey to Atlanta and Los Angeles, charts the artist’s brief however prolific profession. Over the course of eight years, he created some 1,000 works earlier than his premature dying at 28 in 1966. Thompson’s beautiful pictures are outlined by their high-impact visuals—their surprising and electrical colours that he purposefully rendered flat. Artist Robert Colescott as soon as stated of Thompson’s artwork, “When you think you’ve got it—‘sure, it’s about Black and White’—you find out it’s really about red and purple.”

The exhibition’s title takes its name from a modestly sized 1960 oil-on-board work in which a Black figure stands at the composition’s center; in the upper left corner is a red house. As with many of his works, the expressionistic strokes border on abstraction. The piece is the only work Thompson ever titled in the first person and, according to the wall text, “hints at his larger ambitions. Working in the midst of the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, Thompson confronted centuries of dispossession head on in his art and synthesized a new visual language from European artistic traditions.”

In her opening remarks, Davis asked the audience to think deeply about Thompson’s claiming of a space all his own: “If you read over those doors, it says, ‘This House Is Mine.’ What does he mean by that? What would you mean by that? If your label the artwork you created from live experiences, what would you say by saying ‘This house is mine.’”

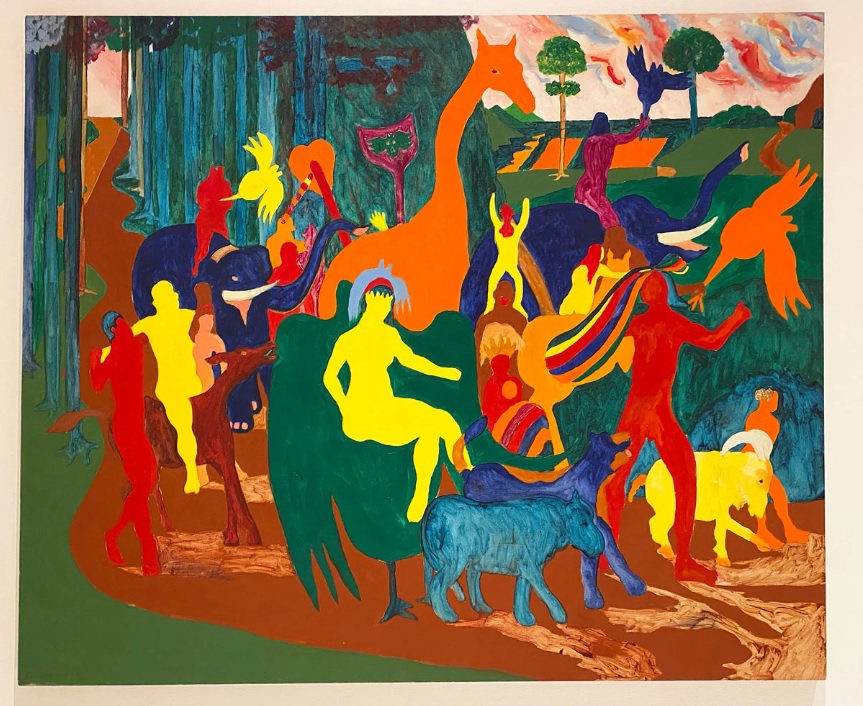

As with many artists before him, Thompson looked to the giants of art history as points of departure, using pieces by Piero della Francesca, Tintoretto, Titian, Poussin, Goya, Gauguin, and Munch as inspirations. Greco-Roman myths and bacchanal and pastoral scenes also served as important sources for Thompson. He put his own spin on these historical images, however, and generated a universe was that was entirely Thompson’s.

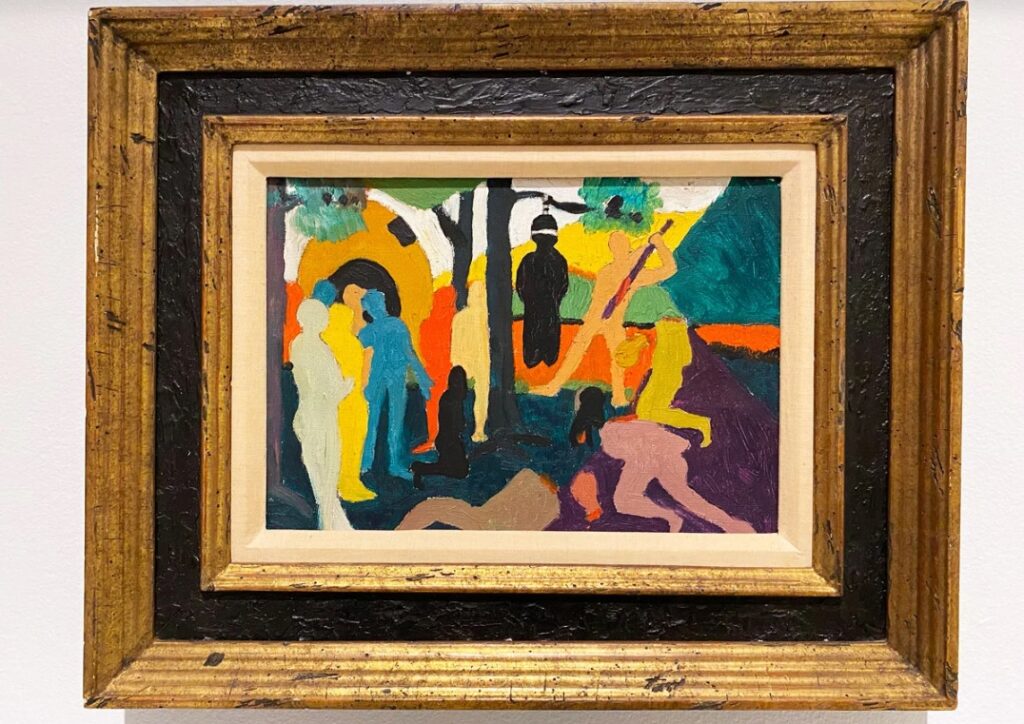

A particularly poignant work, The Execution (1961), is loosely based on Fra Angelico’s Beheading of Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian (1438–40). Whereas Fra Angelico has Saint Cosmas waiting to be beheaded at the center of the composition, standing over his brother’s decapitated head and body, Thompson has rendered Saint Cosmas as a Black man who hangs from a tree as an executioner beats him. The work is a clear invocation of the history of lynching of Black people in the U.S. We cannot forget these brutal histories when imagining new futures, Thompson seems to say.

Prior to the evening’s program beginning, the band played instrumental music that could be heard throughout the galleries. Thompson’s music pulsed in response. On the walls, Thompson’s rich colors appeared to thrum alongside these sounds. In the jovial painting Triumph of Bacchus (1964), for example, a group of processing figures radiate and dance.

All in all, Thompson’s work was a way to grapple with how art history—and his spiritual artistic teachers—had long excluded Black people from the canon. In his hands, the possibilities of life with freedom achieved are endless.

As Rashid Johnson writes in the show’s catalogue, “Rarely have I come across the work of a Black artist in which the characters are cast so freely in outdoor settings. Thompson’s protagonists flow unencumbered through colorful landscapes, redefining topographies and authoring their own fates.”

The night’s program began as four vocalists dressed in purple—Davis, Mz. Reese, Devyn Longstree, and Kayla Henderson—took to the stage to sing powerful renditions of classics like “Feelin’ Good,” “I Put a Spell on You,” and “Mississippi Goddam,” ending with all four women joining to croon “Young, Gifted and Black.”

As Dorian H. Nash, the Smart Museum’s interim manager of public programs, said just before the final song, “By invoking [Nina’s] spirit here in this place, we wanted to embody what it was to think about how art can influence change—real change.”