Staff at the National Galleries of Scotland, which recently acquired the David Allan painting, hope to uncover more information about the sitter’s identity

A small watercolor recently acquired by the National Galleries of Scotland could be one of the earliest known portraits of a Black person by a Scottish artist, notes a statement.

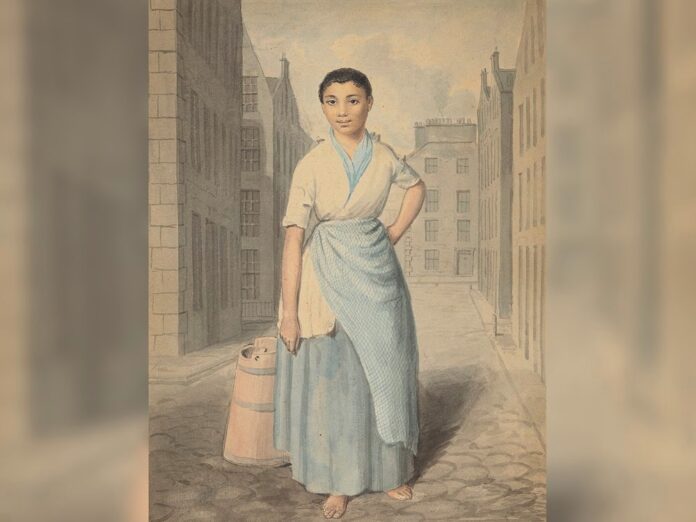

Painted by David Allan between the mid-1780s and early 1790s, the work on paper—titled Edinburgh Milkmaid With Butter Churn—depicts a woman in a white and blue dress. She stands alone, barefoot, in the center of an Edinburgh street, resting one hand on her hip while locking eyes with the viewer.

Based on the large vessel at her feet, scholars have concluded that the portrait’s subject was likely a servant or milkmaid. Clues regarding her name and other identifying details are scarce, but experts are researching the work and hope to uncover more information about it in the months to come, BBC News reports.

Biographical details about the portrait’s painter are more readily available. Born in the Scottish town of Alloa in 1744, the artist relocated to Italy in 1767, remaining there for the next decade or so, according to the National Galleries (a consortium of five Scottish museums). His most famous paintings from this period depict scenes from classical antiquity, including Cleopatra Weeping Over the Ashes of Mark Antony (1771) and Hector’s Farewell From Andromache (1773), reports Shanti Escalante-De Mattei for ARTNews.

While abroad, Allan developed a knack for sketching bustling street life in urban hubs such as Rome and Naples. Upon his return to Scotland in 1779, he became one of the first artists to paint scenes of Scottish life from “across the social hierarchy,” per the statement.

Allan settled in Edinburgh and dedicated himself to creating watercolors and aquatints of ordinary Scottish people. His Edinburgh Characters series, begun in 1788, features individual portraits of soldiers, coalmen, fishwives, lacemakers, salt vendors, firemen, maids and other workers, posed with the tools of their trade and framed against the backdrop of the contemporary city. The artist often used these generic “characters” to populate his panoramic renderings of Edinburgh’s busy streets, including High Street From the Netherbow (1793).

Despite Allan’s propensity for drafting generic “types” of people, curators believe that the recently acquired watercolor was based on a real model. As researchers say in the statement, the milkmaid’s detailed facial features and clothing indicate that the work is “clearly a portrait of a specific person.”

Edinburgh Milkmaid With Butter Churn is currently undergoing restoration but will eventually go on display at the National Galleries.

“We are so pleased to bring this remarkable, rare and extraordinary watercolor into Scotland’s national collection,” says curator Christopher Baker in the statement. “It is an incredibly striking and special work, one which we believe will be enjoyed by many and, we hope, lead to new research on its background and most importantly the story of the woman depicted.”

Researchers encourage anyone with useful information about the watercolor or the sitter’s identity to contact the National Galleries.

People of color appear frequently in European early modern fine art but are often relegated to marginal or subservient roles. Milkmaid is somewhat unique in that its subject takes center stage in the composition.

The woman pictured in Allan’s watercolor could have been one of the many people of African descent who settled in Europe during the 18th century as a result of the transatlantic slave trade. Scottish scholars have been slow to reckon with their country’s participation in the slave trade, wrote Alasdair Lane for NBC News last year. But many Scots made their fortunes through the capture, sale, deportation and exploitation of African people throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, notes the National Library of Scotland.

After Scotland united with England in 1707, Scots played an influential role in British colonies, particularly Guyana and Jamaica. As historian Stephen Mullen writes for the Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery, “[W]ealth poured into Scotland from the labor and suffering of enslaved Africans in Jamaica.”

By the time that Allan painted this work in the late 18th century, many formerly enslaved people in Scotland were fighting for their legal rights in the courts—including Joseph Knight, who was enslaved in Jamaica but moved to Scotland, reports Martin Hannan for the National. Knight won his freedom in a landmark case against his one-time enslaver, John Wedderburn of Balindean. After two appeals, the Scottish Supreme Court ruled in favor of Knight, effectively deeming slavery illegal in the country in 1778, according to the National Records of Scotland.