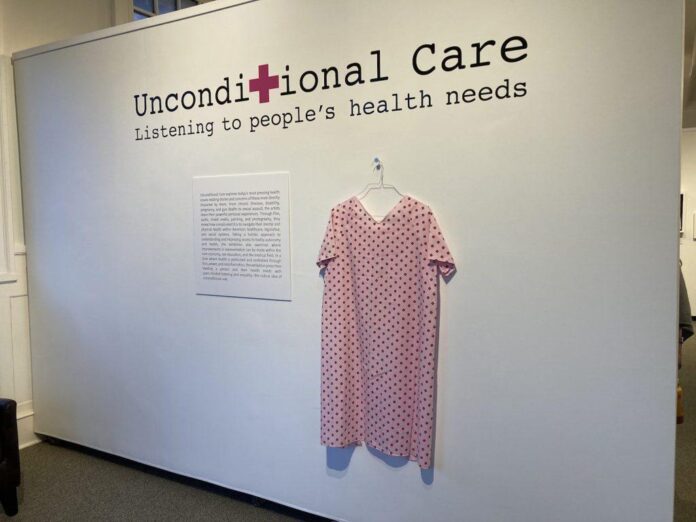

Half a dozen artworks were removed from a show at Lewis-Clark State College Center for Arts and History, a public college in Idaho, because of references to abortion and related reproductive health issues. The show, titled “Unconditional Care,” opened just days ago, on March 3, and is intended as an exploration of “today’s biggest health issues and… stories and concerns of those directly impacted by those issues,” according to an earlier show statement on the school’s website.

It examines topics such as chronic illness, disability, pregnancy, sexual assault, and gun violence including related deaths. A mix of local and international artists are featured in the exhibition, many of whom share their personal experiences through film, audio, mixed media, paintings, and photography.

The works that have been removed from the show include a series of four documentary videos from artist Lydia Nobles, in which individual women share diverse experiences around reproductive rights and pregnancy; a 2023 piece by Michelle Hartney, which is a handwritten copy of one of the 250,000 letters addressed to Margaret Sanger, the founder of Planned Parenthood, and received in the 1920s mostly from mothers who were begging for information about birth control; and a 2015 embroidery work from artist Katrina Majkut titled that depicts Mifepristone and Misoprostol, two prescriptions taken together in sequence to end an early pregnancy.

The college did not immediately respond to a request for comment, but in a statement released to other publications, a spokesperson said of the censorship of the show: “After obtaining legal advice, per Idaho Code Section 18-8705, some of the proposed exhibits could not be included in the exhibition.”

Section 18-8705 is part of the No Public Funds for Abortion Act (NPFAA) that was passed by Idaho’s Republican legislature in 2021, months after the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the right to an abortion.

Majkut is not only a participating artist, but also a guest curator of the show. She told Artnet News that in her 10 years of extensive work with colleges, in particular, she always strives to be bipartisan and objective, while encouraging dialogue and educating viewer. “It’s always been a positive experience. I’ve never heard one peep about discontent. And I’ve never been censored,” she said in a phone interview.

As she and a gallery staffer were developing ideas around the show last fall she was invited to be a curator. “I decided I would do it about the most topical health issues in the United States, as it’s on everyones mind. My goal was to approach these hot topic issues in a very level-headed, factual way,” she said. “I was avoiding protest art. I wanted art that got to the heart of the issue either medically or through personal stories, especially by people directly affected by those health issues.”

Medical Abortion (2015), an embroidery by Katrina Majkut was removed from the show titled “Unconditional Care” at the Lewis-Clark State College Center for Arts & History, in Idago. Image courtesy Katrina Majkut.

Majkut said her work was removed on March 2, a day before the exhibition opened and after giving administrators a tour of the entire show. When informed of their decision to remove the work, Majkut suggested several alternatives including “some sort of presence, even if it just [a statement that reads] ‘this artwork was removed in accordance with the law.’ I said that I wanted the wall text up even if I can’t have the artwork because it literally reiterates Idaho’s own law to the students. That was a no-go. It’s an educational setting, but I was told directly in person that the wall text wasn’t okay.” Majkut said she has dozens of other artworks that remain in the show.

Meanwhile, representatives from the ACLU penned a detailed letter to college president Cynthia Pemberton objecting to the removal of Noble’s works and asking that they be reinstated.

The letter is signed by Elizabeth Larison, director of the arts and culture advocacy program of the National Coalition Against Censorship; by Scarlet Kim, senior staff attorney for speech, privacy and technology project of the ACLU, and Leo Morales, executive director of the ACLU of Idaho.

Stills from Lydia Noble’s documentary series “As I Sit Waiting,” which was removed from the show “Unconditional Care” at Lewis-Clark State College Center for Arts & History in Idaho. Image courtesy Lydia Noble.

They expressed “alarm” at the removal of Noble’s videos.

“The College’s interpretation of the NPFAA—that it applies to works of art depicting the discussion of abortion—demonstrates the potential abuses of the Act,” the letter read. “As the Supreme Court recognized 80 years ago, ‘[i]f there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation, it is that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion…’ The College’s decision threatens this bedrock First Amendment principle by censoring Nobles’s important work and denying visitors of the center the opportunity to view, consider, and discuss it.”

“Institutions of higher education are responsible for presenting students with an array of viewpoints and fostering among them a sense of academic curiosity and intellectual engagement,” it continued. “We urge the College to reconsider this censorship and permit these works to be shown as part of ‘Unconditional Care.’”

Noble said after Majkut invited her to exhibit work from her series, “As I Sit Waiting,” they worked together between mid December 2022 and January 2023 to select four accounts that share diverse experiences around reproductive rights and pregnancy.

“The selected documentaries are that of DeZ’ah, Blair, Cat, and Claudia,” said Noble. “The gallerist and I were working together to figure out installation, and they even painted the wall a light purple to coincide with my ideal installation. All seemed to being going well—that is, until I received an email from the school.”

According to Noble, the email stated: “Upon review of submitted work for the upcoming Center for Arts and History exhibit ‘Unconditional Care,’ after consulting with legal counsel and based on current Idaho Law (Idaho Code 18-8705), your proposed exhibit cannot be included.”

Noble said she asked for further clarification about what exactly in her documentaries violated the law, but she did not receive a response.

“It was also alarming that the language in the email shifted, suggesting that these were just proposed works, when in fact they were installed already; besides slight remaining details,” she said. “The email from the school was particularly odd because I went to great efforts to frame these films as unbiased as I could. I didn’t want to know too much about the participant’s story beforehand. I also wanted the interviews to be memory-based and without an agenda. So to hear that the school thinks that these stories are violating this law, I was pretty confused.”

Artwork by Michelle Hartney that was removed from “Unconditional Care” at Lewis-Clark State College Center for Arts & History, in Idaho. Image courtesy Michelle Hartney.

Of her letter-based work, Hartney told Artnet News: “At the time, even sharing information about pregnancy prevention could land you in jail. Many of the folks who wrote to [Sanger] were suicidal, struggling with major health issues, suffered countless miscarriages and/or stillbirths, or were being physically abused by their husbands, or their husbands were abusing their children. Many of their husbands forced their wives to have sex. Most of the mothers simply wanted the suffering to end and did not want to bring another child into the world to endure the poverty or abuse they would face.“