In the wake of the Supreme Court ruling overturning the landmark ruling allowing states to outlaw abortion, many turned to social media to express their outrage at this assault on reproductive health.

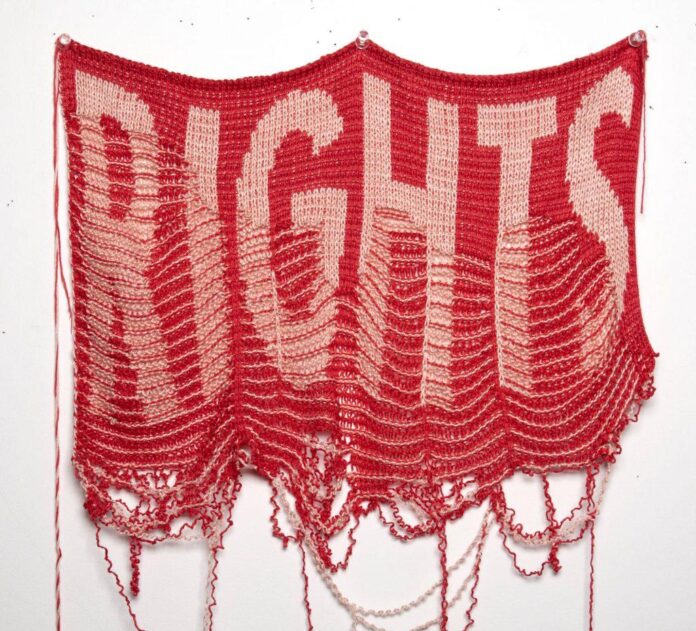

One widely shared image that seemed to perfectly illustrate what was at stake was Lisa Anne Auerbach’s , a short animated video of a knitted artwork proclaiming the word “rights.” Over the course of just a few seconds, the textile unravels, its message eventually disintegrating into complete illegibility—echoing the loss of women’s rights in the U.S.

The piece is just one of Auerbach’s pointedly political knit works, which were the subject of a solo show, “Lisa Anne Auerbach: Unraveling,” this spring at Los Angeles’s Gavlak gallery.

We spoke with Auerbach about the piece’s viral success and how she came to embrace the unconventional medium of knitting in her work.

Lisa Anne Auerbach. Photo by Daniel Marlos, courtesy of the artist and Gavlak Los Angeles and Palm Beach.

When did you first make the piece and what inspired it?

was the first piece I made that I unraveled after knitting it. I’ve been creating knitted work for a long time and always had bound off my edges. I intended to reflect a world that was literally fraying in a visceral way.

Also, I am thinking about textile vernacular and its parallels with matters of community and culture. Concepts such as “tight-knit” communities, “woven” or “stitched” together, or “rippling,” “at loose ends,” “bursting at seams,” and “unraveling.” We use such terms to describe democracy without thinking about why we do so. Seeing the work come apart is a return to the reference in an embodied and tangible way, and I find this physicality of linguistic terms impactful.

You first shared a still image of in September. Do you feel differently about the work now following the Supreme Court’s abortion ruling?

I made the first version of this piece last September concerning the Texas statute encouraging vigilante enforcement of abortion laws. As a result of the Supreme Court ruling, I wanted to see how much I could deconstruct this before losing the word.

At a certain point in these unravelled works, the letters start to collapse, leaving behind only illegible strands of yarn. How does that speak to the effect of the Supreme Court’s decision?

The overturning of felt like an overwhelming collapse where seemingly secure human rights were suddenly dismantled. I wanted the piece to reflect that idea of dissolution. When unraveled, the pinks suggest bodily interiors, organs, tissue.

The feeling of the Supreme Court decision was visceral. Like so many others, I characterized it as a “gut punch,” and the strands of yarn are twisted, gut-like, visibly tangled, fallen apart, hopeless, “at loose ends.” It’s a long way towards rebuilding freedoms we took for granted for many years. The strands of yarn, once a word, an idea, even a truth, are an analog for the feeling of something so broken, such a tangled mess.

The initial still image of the work was only half unraveled, but the video completely undoes the entire piece, unlike the halfway unraveling knitted slogans in your recent show at Gavlak Gallery. Is it actually two separate versions of the work? Did you pause midway through to take photos and then continue unraveling?

There are two versions. I kept the initial piece intact and made a new one to unravel the work completely.

Two days after the deadly school shooting in Uvalde, Texas, you shared a similar time lapse video of an unraveling work called . Was that a piece that you made specifically in response to the massacre there?

Yes. Usually, politicians and leaders make these statements after mass shootings, but at this point, the cynicism of the words has been addressed repeatedly, so we don’t hear it as often. Regardless, the words are intended to represent political inaction in the face of this ongoing senseless, horrific tragedy.

When did you first learn to knit? Did you learn to knit specifically for your art practice, or was it a practical skill that you later incorporated into your art?

I learned to knit after leaving grad school. Until that point, my primary medium was photography. When I graduated, I lost access to a darkroom, and this was before the ubiquitousness of digital processes. So I learned to knit to continue my art practice at the time. Through the physicality or materiality of text, I was interested in how this process could transform the meaning of a word. I loved the sweaters Sally Walton made for Rick Nielsen in Cheap Trick. Text knit into a sweater becomes an integral part of the garment, not an addition but the structure itself.

Lisa Anne Auerbach, (2022). Photo courtesy of the artist and Gavlak Los Angeles and Palm Beach.

What was it that appealed to you about political knitting, about bringing a female-centric craft into the activist realm and into the world of fine art?

I started knitting to make sweaters with text on them, to make words into fabric, to turn what I was thinking about at a particular moment into a garment that would outlast its sentiment. I wasn’t thinking about gender or activism or politics. “Political knitting” wasn’t really a thing when I started knitting.

How have your knitting skills evolved over the past two decades? Do you create templates for each work?

Most of the work I exhibit is machine knit, and I’ve used the same machine since 2004.

“Lisa Anne Auerbach: Unraveling” (2022) at Gavlak Los Angeles. Photo courtesy of the artist and Gavlak Los Angeles and Palm Beach.

How do you come up with the slogans to incorporate into the knit works?

Sometimes I start with an idea of what I want to make a work about, other times a phrase will pop into my head or I’ll hear something in a song, or read (or misread) text. At times I will use historical slogans. I try not to knit the obvious, but in some cases, it’s the obvious that makes the most sense.

Do you have a favorite knit work that you’ve made, and why?

My favorite piece is usually the one I’ve made most recently. It’s my favorite until I make my next favorite.

That said, there are a few made over the years that I still really love, like the series of large knitted bookshelves that create portraits of book lovers through their libraries. A hand knit sweater with a big Jewish star on the back is one of my all time faves, but it’s now in the collection of the Hammer Museum [in Los Angeles] so I can’t wear it anymore, which is a bummer. A 9/11 joke sweater is another one I always liked a lot, too, but it’s also gone. “Keep abortion legal” used to be a fave, and I wore it for years as we saw reproductive rights get chipped away. Can I even wear that one now?

How often do you wear your own sweaters?

I live in Los Angeles, so I don’t wear them as much as I’d like. I keep a few in my office that I wear when it’s chilly, and during our cooler months I’ll usually take a few to rotate over the winter.

When did you start unravelling your knit works? Was it in response to a sense of impending doom for our society and the human race, or am I reading too much into it?

Your question about impending doom is accurate. In other projects, I look at far-right spaces online, so I’m thinking a lot about civic issues around cohesion and dissolution. I wanted to express this using a familiar medium.

Steve Bannon often talks about the book , which describes a cycle in history that is characterized by individualism and the decay of old civic orders, making way for new ones. I was not familiar with this theory when I began the pieces. The process was organic, one of material exploration rather than a literal illustration. Again, this underscores the ubiquity of how the language of textiles and political structures are woven together.

Lisa Anne Auerbach, (2022). Photo courtesy of the artist and Gavlak Los Angeles and Palm Beach.

How does it feel to undo something you’ve spent so much time on? And how long does a typical piece take to knit versus to unravel?

The pieces that are unraveling are machine knit, which certainly doesn’t make the process instantaneous, but it’s a lot quicker than hand knitting. I’m not as interested in the process as I am in what it makes. Things take as long as they need; sometimes there are technical hiccups and they can take forever, and other times everything goes smoothly.

When did you realize that if you were going to unravel these pieces, that you should film the process?

was the first one I photographed while I was taking it apart. I conceptualized it as a video rather than as a static work. The pieces that are in the midst of unraveling retain legibility to a degree, I wanted to see how it would look completely undone and photographed it as an animation to document the process.

Lisa Anne Auerbach, (2022), video still. Photo courtesy of the artist and Gavlak Los Angeles and Palm Beach.

Does unraveling a piece half way present any conservation challenges? How do you prevent the works from continuing to unravel?

It takes a lot of effort to separate them; they won’t just fall apart on their own. Unless some real effort is put into it, there is a low risk of further unraveling.

Rights