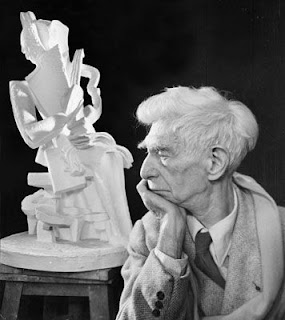

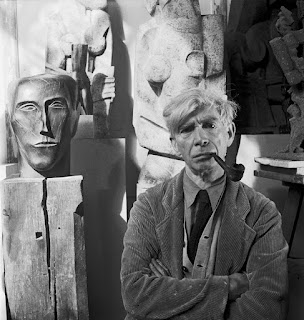

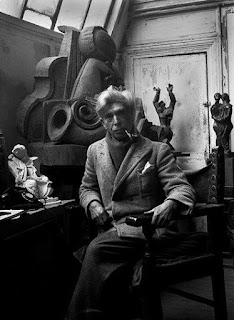

Ossip Zadkine was a pioneer in applying the principles of Cubism to sculpture. His striking compositions reduce the human figure to geometric forms and emphasize the dynamic interplay of concave and convex surfaces. This approach creates a unique and captivating visual experience for the viewer. Throughout his long and illustrious career, Zadkine gained worldwide recognition for creating powerful and bold visual statements. His work often addressed the atrocities of the twentieth century, some of which he had witnessed during his military service in World War I. Despite these traumatic experiences, towards the end of his life, Zadkine reflected in his memoir: ‘But it is in any case very beautiful to end your life with a chisel and mallet in your hands.’

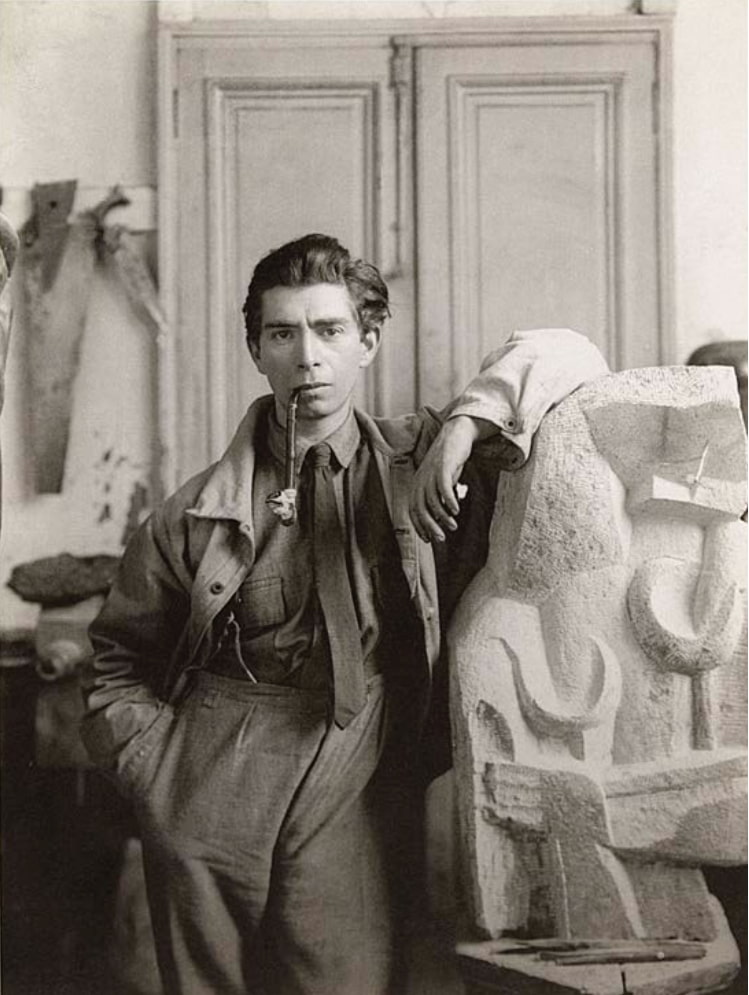

Zadkine was born in Vitebsk, which is now in present-day Belarus. Although there is some uncertainty about his exact birth year, it is believed to be around 1890. Despite his father’s disappointment that he was more interested in clay art than academics, Zadkine pursued his passion and became a renowned sculptor. At the age of fifteen, he was sent to live with relatives in Britain to improve his English and manners, an experience that would shape his artistic career. Zadkine was introduced to woodworking and found employment in a London cabinet-making shop where he proved to be especially adept at carving furniture ornamentation. He further honed these skills by attending evening classes at the Regent Street Polytechnic. Despite a harsh rejection by the young British sculptor Jacob Epstein, Zadkine’s confidence in his artistic talents remained unshaken. His father recognised his potential and sent him to Paris to enrol at the École des Beaux-Arts. It was there that he would develop his unique style and become a renowned sculptor. Sadly, years later, Zadkine would learn that his parents had died during the Bolshevik Revolution.

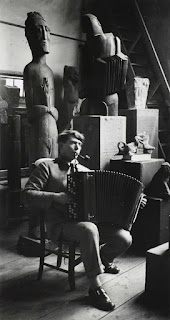

Zadkine arrived in Paris during the peak of Cubism in 1910. During this time, Cubist artists like Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso were breaking down subject matter into abstract geometric elements presented from multiple perspectives, both in two and three dimensions. After six months at the École, Zadkine left to join the avant-garde artists Marc Chagall and Amedeo Modigliani at La Ruche, an artist’s enclave in the Montparnasse area of the city. Zadkine chose to abandon his academic style and instead dedicated himself to the art of direct carving. This method allows the carving process to determine the final shape of the work, whether in wood or stone.

During World War I, Zadkine served with the French Army from 1916 onwards. He was assigned to the First Foreign Regiment, a division of the French Foreign Legion, where he focused on medical transport and caring for wounded soldiers. After being severely gassed, Zadkine was discharged in 1917 and returned to Paris. He described himself as ‘physically and morally devastated’. Zadkine documented his harrowing experiences on the front in a series of etchings published the following year. In May 1920, Zadkine held a one-man exhibition of forty-nine sculptures at his Parisian studio, which received critical acclaim. In the preface to the exhibition catalogue, the French art historian George Duthuit praised the powerful ‘bare simplicity’ of the works and ranked Zadkine as one of ‘the greatest craftsmen of the moment.’ It is clear that Zadkine’s talent was recognized early on, and his reputation only grew as he continued to experiment with plaster or clay models that were subsequently cast in bronze. His success was solidified through a series of successful one-man exhibitions in London, Brussels, and New York. It is evident that Zadkine’s dedication to his craft and his willingness to take risks paid off in the end.

As the Nazi regime advanced into France, Zadkine, who was of Jewish descent, fled to New York in 1941 on one of the last American passenger ships to leave Europe. Despite being able to bring only his most essential art tools and supplies, Zadkine exhibited a series of gouache paintings at the Galerie Wildenstein in New York. Zadkine fondly remembered his time in America, although he admitted that it was a challenging period in his life. ‘I must admit, I was feeling a bit uninspired lately. It felt like I had left the best part of myself back in France’. However, despite these challenges, Zadkine’s career as an art educator flourished during his American exile. He was an excellent teacher at the Art Students League, and even mentored Elizabeth Catlett, inspiring her to incorporate abstraction into her sculpture. In 1945, Zadkine was invited to teach sculpture at Black Mountain College in North Carolina. He had the pleasure of working alongside Jean Varda and Leo Amino.

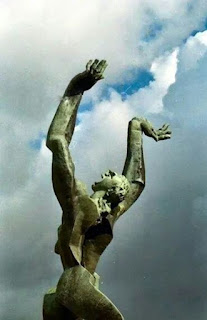

After returning to Europe that autumn, Zadkine expressed his response to his own trauma and the devastation of the continent through works featuring fractured forms, voids, and contorted poses. Zadkine was confident in his ability to create a sculpture that would honour the city’s history and resilience. The city of Rotterdam, which had been heavily damaged during the war, commissioned him to create a monumental public sculpture. The Destroyed City, which stands at twenty-one feet and took two years to make, depicts a distorted figure with its head tilted back and arms reaching towards the sky. This sculpture is infused with palpable anguish and is heralded as Zadkine’s masterpiece. He described it as ‘a cry of horror against the inhuman brutality of this act of tyranny.’

Between 1946 and 1958, Zadkine served as a professor of sculpture at L’Académie de la Grande-Chaumière in Paris. He was enthusiastic about implementing the innovative pedagogical practices he had learned at the Art Students League. In 1948, the Ossip Zadkine Studio of Modern Sculpture and Drawing was established, which received approval for GI Bill tuition funding and attracted a large number of American students, including Kenneth Noland, an alumnus of Black Mountain College and a veteran. Zadkine was a highly acclaimed artist, receiving numerous awards throughout his career. These included a major retrospective in 1949, the sculpture prize at the 1950 Venice Biennale, and the French Grand Prix National des Arts in 1960. Sadly, he passed away in 1967 following abdominal surgery. However, his legacy lives on through his artwork, which was generously donated by his widow to the city of Paris. Today, his home and artwork can be enjoyed by all at the Musée Zadkine, which opened in 1982.

The statue by Ossip Zadkine stands on the Vincent van Goghplein in Zundert, in front of the Van Gogh Church, and not far from the house where both of them were born. It was unveiled on 28 May 1969 by Queen Juliana and the Mayor of Zundert, G.J.A. Manders, and in the presence of Ossip Zadkine.

The work of art, which includes a thick base, is cast from bronze, and without its pedestal is about two and a half metres high. The whole statue has weathered in a bronze green, a colour that over the years has spread to the lightly coloured pedestal. The lines, the expressive hands and the space between the men’s bodies remind us of Zadkine’s statue The Devastated City (De Verwoeste Stad) in Rotterdam. The two men in the Zundert statue are holding hands, and their heads touch. The man seen on the right from the front is wearing a collar as an indication of citizenship. Zadkine did not try to portray a likeness to the Van Goghs’ faces.

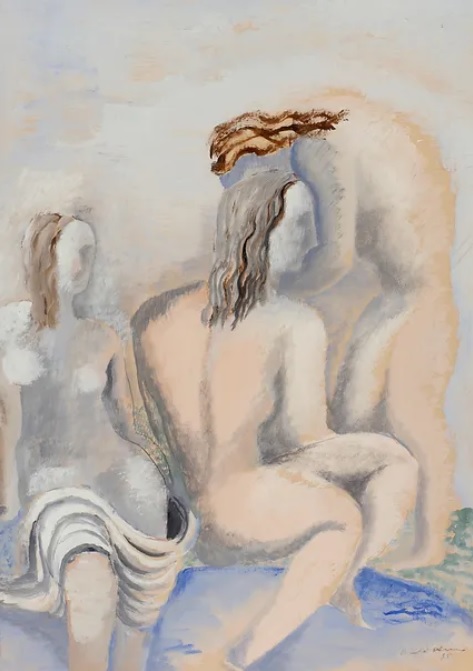

Uncovering Ossip Zadkine’s Artistic Prowess in Painting and a Unique Look at ‘Bathers’ by Malab’Art Gallery

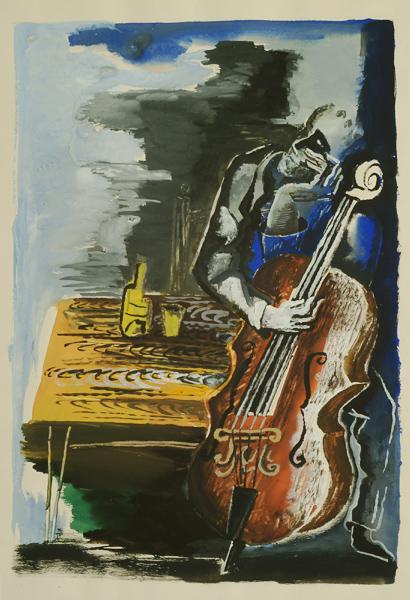

There are over 612 sculptures and a large number of works on paper, 765 gouaches and drawings, as well as 200 lithographs and etchings created by Ossip Zadkine. His Parisian studio of the rue Rousselet exhibited his works on May 20th, 1920, marking the beginning of a long series of shows. He had over 105 solo exhibitions during his lifetime, in Europe, the United States, and Japan.

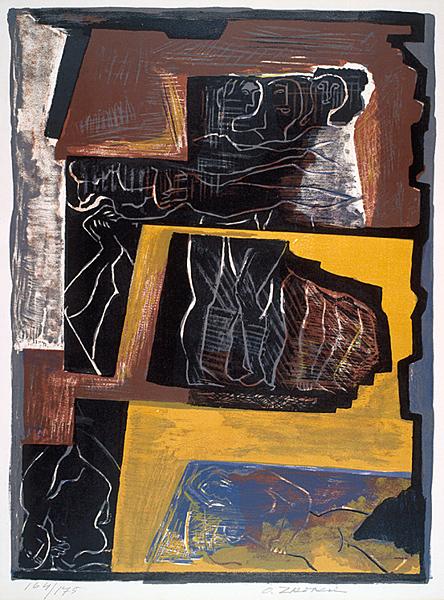

Malab’Art, a gallery based in London, is exhibiting a unique painting by Ossip Zadkine called ‘Bathers’ (1935).

Ossip Zadkine ‘Bathers’ [1935]

Gouache on cardboard (55 x 40 cm)

His remarkable artistic production includes more than four hundred sculptures, thousands of drawings, watercolors and gouaches, engravings, illustrations for books and tapestry cartoons.