In the early ’90s, the artist and critic Lorraine O’Grady wrote the report “The Maid of Olympia: Restore Black Female Subjectivity”, dedicated to the famous painting by Edward Manet. The article was positioned as the first of its kind critical work on the black female body in art. In the distant 1992, who would have thought that there would be a whole wave of researchers, curators, etc., who would turn to the essays of the black artist. For example, there is a special evening in MOMA (it explains “why it is interesting”). Then, Denise Marrell from Columbia University saw “Olympia” at one of her lectures. She was interested in how the teacher would tell about the black maid: he would use racist terminology or formulate something in the context of modern thought. The teacher did not say anything about the black woman in the painting, and this surprised Deniz most of all, although, obviously, she would have a claim to any scenario. And she started to study how people of black race were depicted in the painting, because “there were exponentially fewer articles on black figures than white ones”.

Then Denise discovered that, as it turns out, among the French impressionist artists – and in general Paris in the late 19th and early 20th centuries – there were many black women who were models, mistresses (remember at least the muse of Baudelaire Jeanne Duval). Of course, it was a discovery, but the black explorer could not stop. She defended her dissertation, then made an exhibition. It was difficult to find the money for the project until Darren Walker became director of the Ford Foundation, who, according to Artnet, “began to limit the distribution of grants in accordance with the idea of art and social justice. Luckily, Darren Walker is also black plus open gay. The exhibition entitled “Black Model from Manet and Matisse to the Present Day” opened on October 24, 2018, at the Wallach Art Gallery, and the exhibition “Black Model from Gericault to Matisse”, a more expansive version, opened at the Orsay Museum in March 2019.

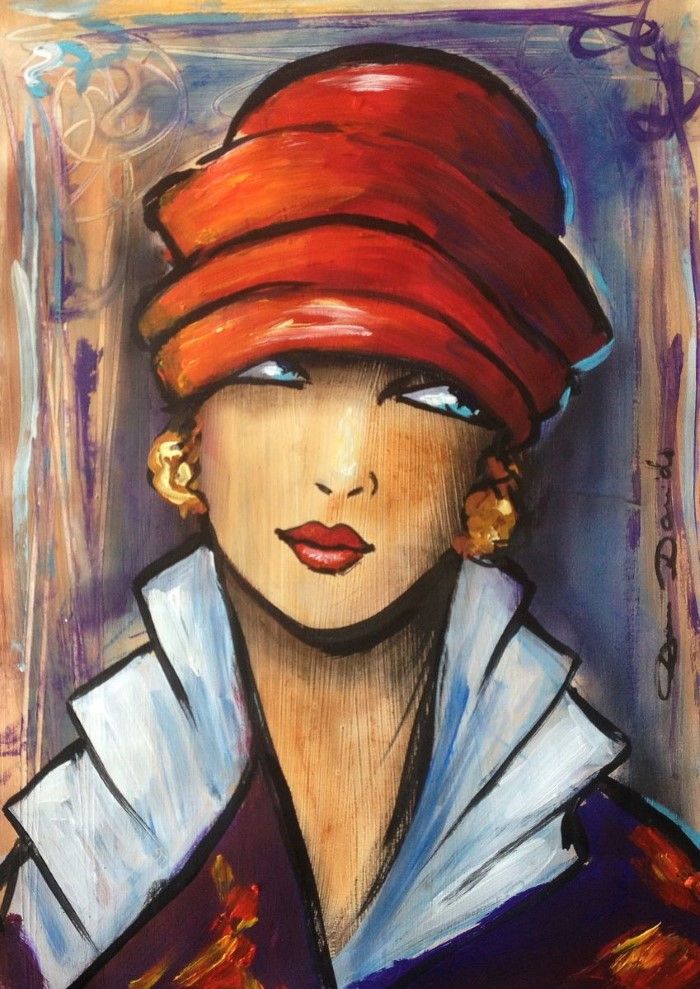

Released subjectivity. Dam Domido

His work is based on the search for “freed subjectivity”, built on sublime emotions, where each detail has its own color and rhythm.

Dam Domido is a modern French artist, photographer, and sculptor. As an artist, he works in oil technique, in the styles of the lyrical abstraction and figurative expressionism.

His work is based on a search for “freed subjectivity”, built on sublime emotions, where each detail has its own color and rhythm, the purpose of which is to reveal the full force of a character or object on the canvas. Most of Dam’s paintings in the figurative expressionism style are the urban landscapes of the French capital, but there are also paintings made of a mixture of figurative expressionism and art deco styles.

Art Deco is Domido’s favorite style in general, as well as the era he describes. Women in the clothing of the twenties can be seen in many of his paintings, made in both the style of realism and abstraction. Dam Domido’s works are present in public galleries and in many international collections, especially private ones.

Pop Art & Women

A woman has long been one of the favorite subjects of Western painters. The tradition of lying naked goes from Titian to Matisse, and from him to Wesselman, who paid tribute to her in the series Big American Nude. The woman lying in a sensual pose is given a passive role: being a simple object of contemplation, she provides her body to create images of desire and femininity. But what happens when this tradition is interrupted and the woman turns from an image object into a creator of art? What happens when female nudity becomes an instrument of sexual liberation, which began in the 1960s?

“Playboy wasn’t meant to be a publication for rich idlers: we understood that the economic boom in postwar America would allow almost any man to be involved in what our magazine calls playboy’s life – if, of course, he was willing to make the necessary effort to do so”.

Hugh Hefner, 1964

Thus, in 1964, its founder Hugh Hefner expressed himself in one of the publications on the pages of a men’s lifestyle magazine. Playboy gave all men access not only to dazzling naked beauties but also to serious pop art – reviews of fashion, prose, and poetry. Offered for a modest price of 50 cents (this is how much the magazine cost in 1953 when it began to be published), eroticism and pleasure became a marketable commodity. According to Hefner’s promise, every man received his share of the “playboy life”, and reversals with naked women in draft positions (including Marilyn Monroe, for example) quickly became the magazine’s main attraction. Women were the protagonists of Playboy, but its target audience was men who gave their partners the place of lust objects on glossy pages.

Martha Rossler in Harem’s photomontage of the Beautiful Body or Beauty knows no pain (1966-1972; pp. 106-107) made an ironic protest against this hierarchy, collecting many clippings with Playboy models in a kind of “herd”, obedient to the eyes of the viewer. This work clearly demonstrated the standardization of eroticism on the pages of the men’s magazine: all women, regardless of the color of their skin and any other features, pose the same way, relying on the sexual requests of the client. Thus, the female body turns out to be an ordinary product. Having criticized Playboy’s bet on soft pornography to the detriment of women’s individuality, Rosler drew attention to the beauty standards imposed by all mass media in general. The true plot of Harem and other photomontages from the same series was the idea of women cultivated by men and for men, which implies catchy makeup, intricate hairstyle, surgical “improvements” of the body, etc. Today recognized as a classic of feminist art, Harem pointed to the extremely contradictory relationship between female nudity and its representation in the media.

“Women had no place in pop art…”

The topic of undervaluation of women in the art world, including pop art, was also not ignored by Rosler. Their role in this direction was considered by critics and historians to be secondary until very recently. Remembering her personal experience as an artist close to pop art, Rossler noted: “Women had no place in pop art. <…> the expression of special, ‘strictly’ female subjectivity was simply not allowed. According to this insightful testimony, women’s subjectivity was the responsibility of male pop artists, who “better” knew how to play with or criticize stereotypical female images. In photomontage The Woman with the Vacuum Cleaner, or Pop Art Cleaner (1966-1972), Rosler was very sarcastic about this marginalization of women in a patriarchal society. The elegant young woman represented at the center of this work performs her household chores surrounded by the works of male pop art heroes (including Tom Wesselman): men do the art, while the vacuum cleaner remains a woman’s job.

Drowning Girl (1963) belongs to the group of works of the artist dedicated to the female face, this close-up. The crying beauty is floundering in the waves, trying not to drown out of her last strength. Retaining, despite the gravity of the situation, attractiveness and pride, the girl assures us through a bubble – a standard element of the comic book, which regularly resorted to Liechtenstein – that she can solve the problem herself. She states categorically: “Whatever happens! It’s better to drown than ask Brad for help!” By Brad, we mean a stereotypical macho hero, ready to save a woman, no matter what she is threatened with. And although the girl, as it seems, does not want to be rescued, it does not cancel the confidence in the implied appearance and triumph of Brad.

In Liechtenstein’s paintings, women often appear dependent on men. According to Letty Eisenhower, the artist’s girlfriend in the early 1960s, his works like Sinking Girl were dictated by the stress of a recent divorce and the desire to establish a simple relationship with someone based on the subordinate position of a woman:

“I am sure that these paintings emerged as an expression of his pessimistic view of ‘romantic love. He put his despair into them, in which he ironically confessed through the title of one of his “crying girls” (Despair, 1963. – F. F.). After the divorce, he did not so much grieve about his lost family as he was disappointed in love. Cynicism appeared in him, which became stronger in 1962 after a short and unsuccessful relationship with one girl photographer from the magazine <…>, who did not wish to continue. He was very worried, but could not cry – and the girls in these paintings are crying for him. Roy wanted some Breck Girl (a dazzling blonde from a Breck shampoo commercial) to love him as much as these girls from his paintings love their boyfriends.

Not as demonstratively erotic as the nude models in Rossler’s paintings, the images of women in Liechtenstein’s paintings – idealized representations of love and feminine weakness – refer, sometimes indirectly and sometimes directly, to the standards of his contemporary soap operas, popular literature and mass media.

The direction of philosophical research that emerged after the publication of Simone de Beauvoir’s Second Floor (1949). The book was written on the advice of J.-P. Sartre in line with the post-Kozhevsky critical rethinking of the Hegelian dialectics of Rab and Mister. As a result, a new discursive criterion – the sexual difference – was introduced into philosophy, which made it possible to distinguish a new philosophical construction of subjectivity – first female, and then gender/transgender, as opposed to the traditional sexless. Female subjectivity is thought of as different in relation to the male type of subjectivation – as a specific “female experience” and corresponding “female” ways of being; hence, special attention to the concept of “female sexuality. At the same time, the structure of female subjectivity is understood as socially constructed: hence, the criticism of the patriarchal relations of power, in which the woman acts not as a subject, but as an object of discourse and practice. In this sense, S. de Beauvoir’s philosophical concept gave rise to two theoretical trends in F.F.: (1) based on the theory of J. de Beauvoir. (1) based on the Lacan and/or J. de Beauvoir theory. Deal with the concepts of female subjectivity outside the realm of “phallic economy” (Philosophiae Luc Irigaray, Hélène Siksou, Catherine Clement, Sarah Koffmann, Amer. – Elizabeth Gross, Joan Kopjack, Jane Gallop, European philosopher Rosie Brydotti), and (2) M. Foucault’s theory-based concepts of female subjectivation as the bodily normalization of power strategies (American theorist J. Butler, Teresa de Lauretis).

The new subject of philosophy (female subjectivity) required new types of discourse and writing practices in a form: (1) the practice of representing female subjectivity and (2) the deconstruction of phallogocentrism, which combines the discourse of feminism with other modern theories of political resistance – in particular, the discourse of post-colonialism. It is no coincidence that many modern feminist theorists are at the same time theorists of post-colonialism, for example. Gayatri Spivak (“In Other Worlds”, 1987 and “There, in a Learning Machine”, 1993), Gloria Anzaldois (“This Bridge that Called Me” with Cherry Moraga, 1981 and “This Bridge We Call Home” with Analouisa Keating, 2002), Emma Pepper (“The Decolonial Imaginary”, 1999). The focus on changing the social order and focusing on the category of action also connects the philosophy of feminism with post-Marxism, one of the founders of which, the political philosopher Chantal Muff (“Hegemony and Socialist Strategy” together with E. Laclau, 1985; “Democratic Paradox”, 2000), is at the same time a feminist theorist. At the same time, F.F.’s main theoretical problem is related to her own basic theoretical intention – an attempt to provide logical justification and representation of the Other in thinking and culture. The paradox, which is fixed by one of the critics of feminism S. Zhijek, is that “the Other” as a discursive category is structurally defined only depending on the binary opposition of identity, and the attempt to represent the Other in thinking is inevitably carried out through the use of traditional logic and the conceptual apparatus. In addition, the modern theory of “otherness” is inevitably linked to the paradox of victimization: “to be different” in modern culture often means the position of “fundamental lack of possession”, i.e. political marginalization and discrimination.

Unlike Y. Kristeva, J. Butler develops the philosophy of “affirmative deconstruction”. The affirmative deconstruction procedure deals with the problem of the subject and the practice of political resistance. Carrying out “critical genealogy of gender categories”, the philosopher, on the one hand, challenges the category of the subject and the category of “human” (norms by means of which “human life” is inaccessible to groups of the excluded). On the other hand, J. Butler argues that the subject is able to repeat the norms of the subject-formation in unexpected and unauthorized ways, avoiding the wrapping up of the dominant norms through their “occupation. Butler’s predecessor, F.F. J. Butler, opposes a theoretical strategy that she calls ‘politicians of discomfort’. According to J. Butler, any attempts by feminism to give a universal or specific context to the category of “woman” that originated from the original guarantees of solidarity are doomed to failure: no basis for action that unites all women can be found. The central theme of J. Butler’s recent works is the coexistence of heterosexual and racist imperatives of behavior. In particular, it is a question of how neocolonial nation-states reproduce traditional gender relations based on state power in former colonies, and how such reproduction affects modern politics. It is a policy in which, according to J. Butler, “whose lives can be labeled as lives and whose deaths will be considered deaths” and in which “national melancholy”, understood as “grief”, inevitably triggers aggression (extra-legal operations of power, which can be carried out solely through militaristic codes).

F.F. had a significant impact on the philosophical thought of the last decades of the 20th century. For example, Y. Kristeva’s ideas influenced R. Bart, E. Siksa’s work influenced J. Bart. Derrida and M. Foucault work by L. Irigarei – on J. Lacan. At present, there is a dialogue between S. Muff and J. Kopjek on the one hand, and E. Laclau on the other; between J. Butler, Renata Saleczl, and Aljonka Zupancic on the one hand, and S. Kristev on the other. Geek, on the other hand, as well as a dialogue of feminist concepts of resistance with the theory of sets of A. Negri and M. Hardt, and with the concept of a “community of equals” by J. Ranciere.