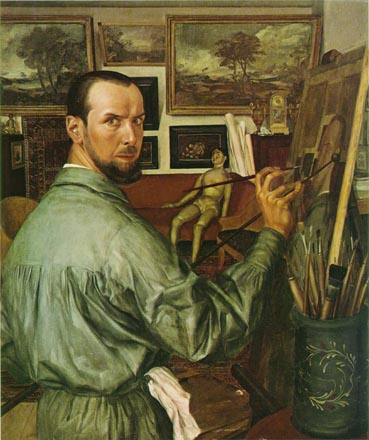

Alexandre Iakovleff (1887-1938) – famous Russian painter, graphic artist, master of drawing, portraitist, author of genre paintings and landscapes, theatre decorator, muralist, headed the art department at the Boston School of the Museum of Fine Arts. Iakovleff was born in 1887 in St. Petersburg in the family of a famous engineer, in 1904 graduated from a real school, two years studied at the school of Ya. С. Goldblatt and in 1905 entered the Academy of Arts. Iakovleff was a learner of Kardovsky and this largely determined his creative destiny. His friendship with fellow students Shukhaev, Brodsky, Lokkenberg, Grigoriev turned into a famous creative team and lasted for many years. Friends studied together, spent their free time together, were fond of Art Nouveau, equally passionate over French Impressionism. Their names in the history of art almost always stand side by side. In summer they often lived and wrote sketches on the Volga and made plans for the future.

During his studies, Iakovleff co-operated with popular publications of the time, for which he made drawings to accompany the text. Iakovleff was an excellent artist and his images were characterised by expressiveness. Iakovleff began to show his works at exhibitions ‘World of Art’ since 1912. His work caused resonance in the press, was even noted in an article by Alexander Benois. Yakovlev was close to the art of the late Renaissance, under the impression of which he wrote the picture ‘Bath’. In 1914 he went as a pensioner from the Academy in Italy, studied the work of the old masters, wrote a lot. He presented his artistic account of the journey with several portraits at the exhibition ‘World of Art’ in 1915.

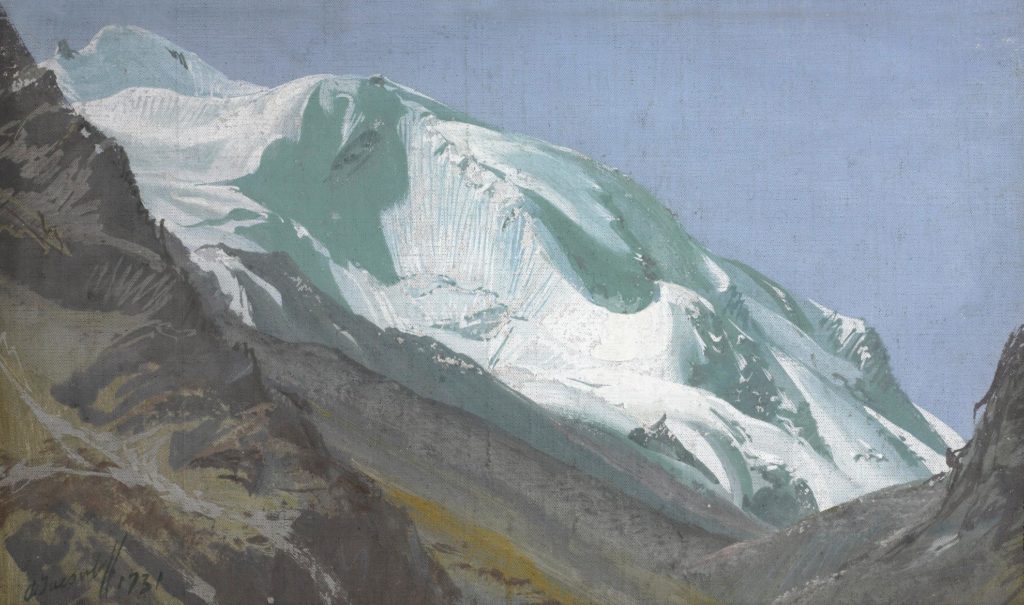

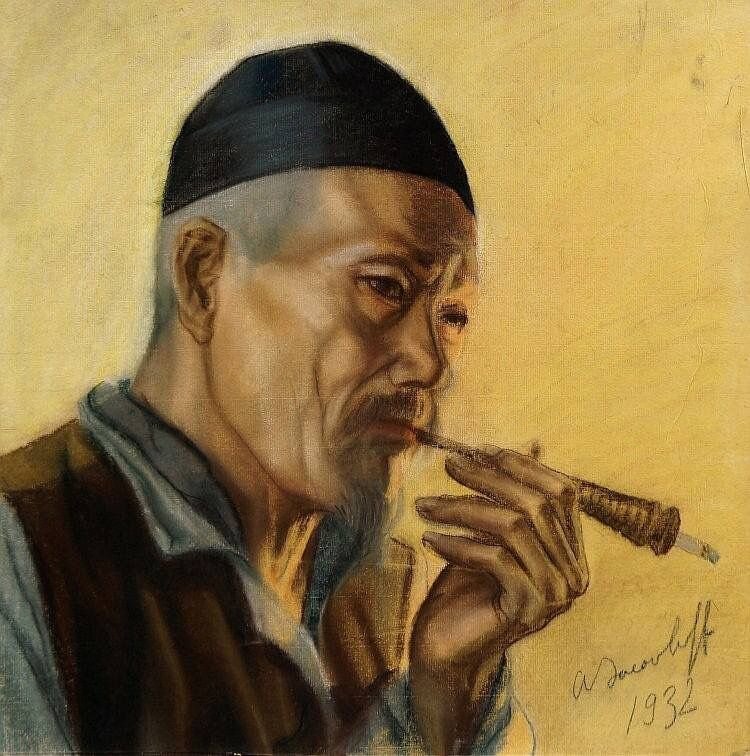

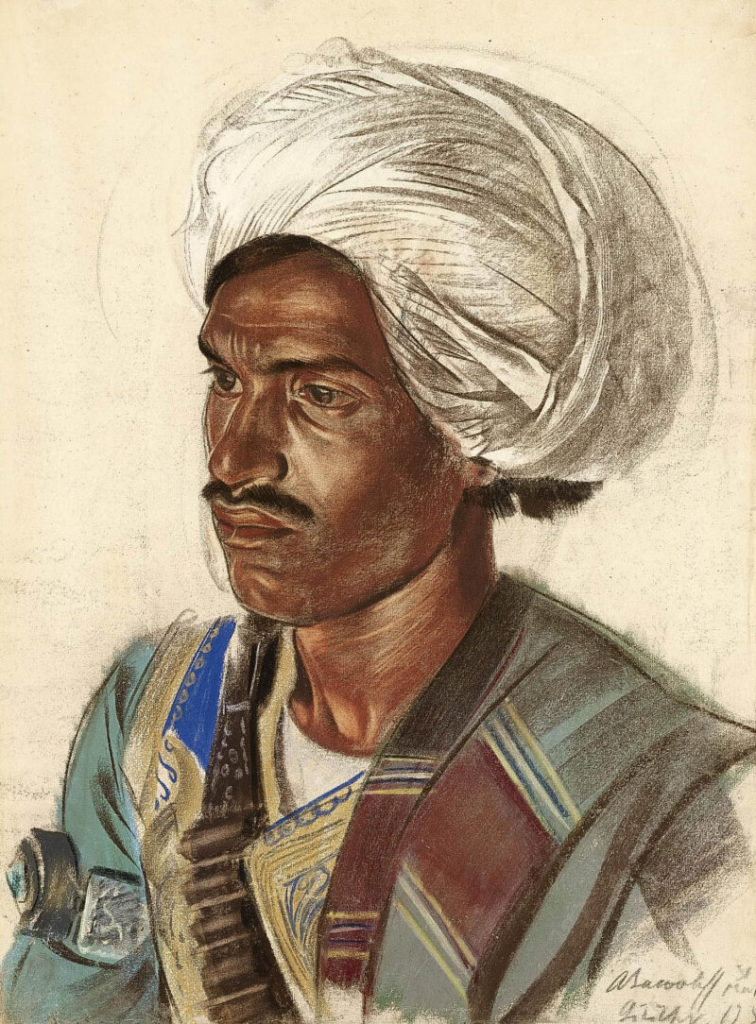

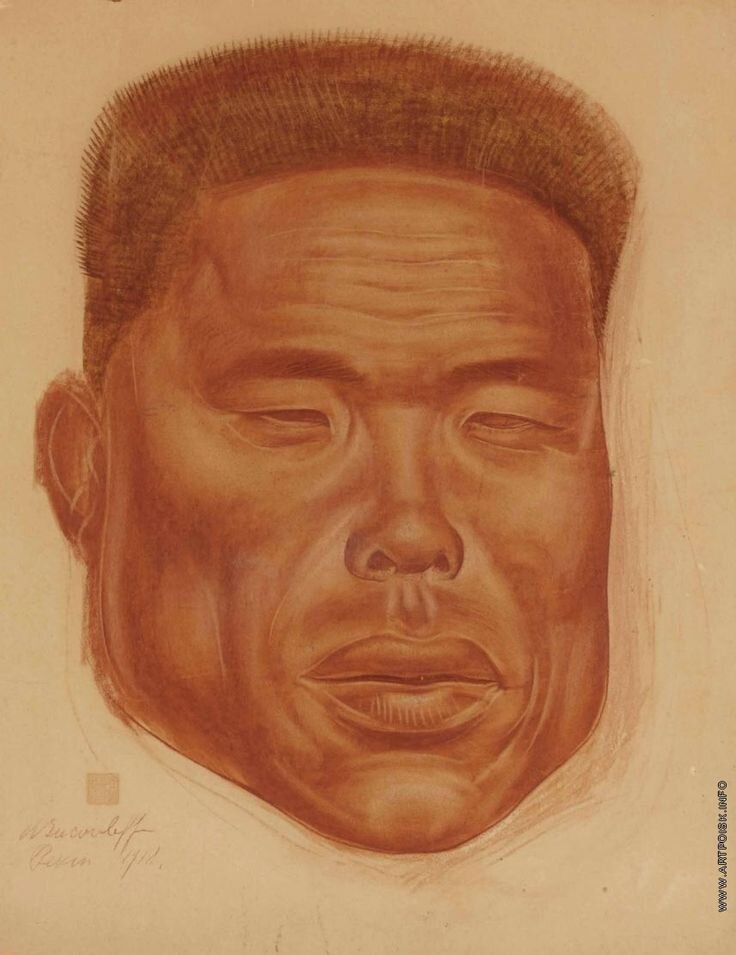

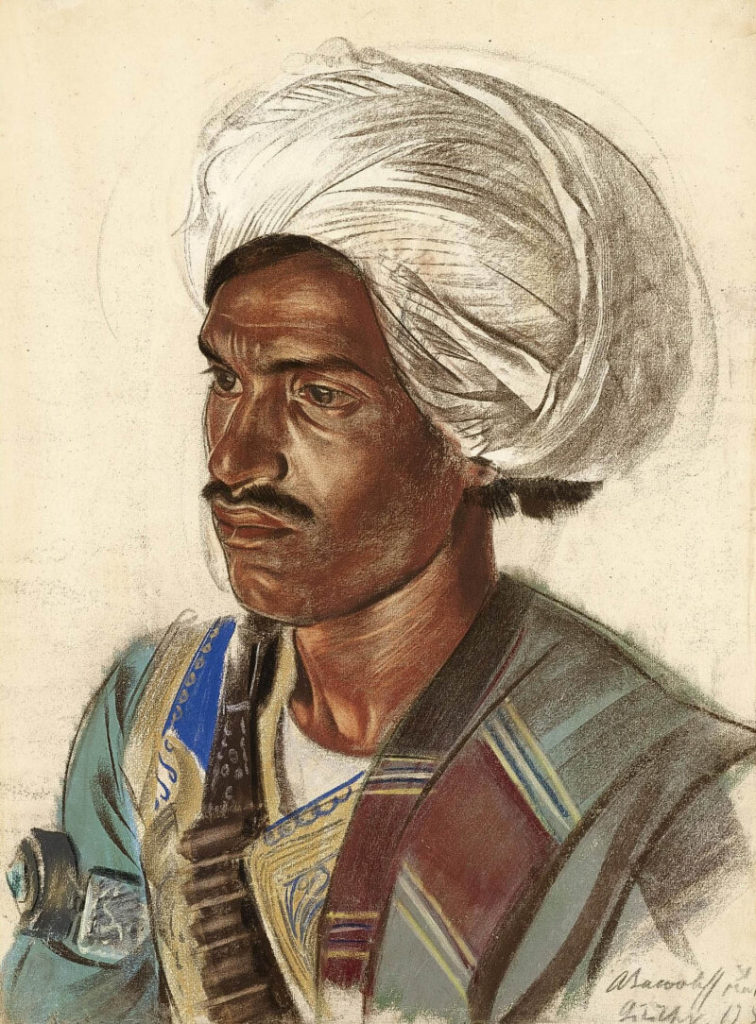

Since 1916 he was engaged in monumental-decorative works: painted plafonds and walls of some Moscow mansions, decorated the interior of the lobby of the Kazan railway station, made sketches for the painting of the Church of St. Nicholas in Italy. Iakovleff was an indefatigable traveller and collected natural material for his paintings in the Far East, China, Mongolia and Japan. He was fascinated by the culture of the East, the exoticism of theatrical performances, the colourfulness of local people. The artist created many sketches, sketches and photographs – the richest ethnographic series of his impressions.

From 1919 Iakovleff lived in Paris, where he first presented his works on oriental themes. The success of the exhibition was so unexpected that the artist was invited to London and then to Chicago. His works were published in several albums in small editions, and the book ‘Drawings and Painting of the Far East’ was designed by his friend Shukhaev. An album about theatre in China Iakovleff made in co-authorship with the writer Zhu Kim-Kima, who wrote the text.

An unforgettable event for the artist was the participation in the African scientific research expedition of 1924-1925 years. The bright exotic nature of Africa, the life of the natives, the colours of the summer heat poured out on the canvases of more than three hundred works. A solo exhibition on the African theme was held in 1926 in the gallery J. Charpentier. For the artist was important this pictorial experience, where honed his skill and diversity of the image of nature. Each new journey of Iakovleff was accompanied by comprehension of new heights of self-improvement. A creative rise in field trips to Ethiopia and Pompeii marks the 1930s. Iakovleff was so impressed by the ancient Roman frescoes that he began to copy them enthusiastically. From this time comes a turning point in his work, there is a new perception of colour, and as a result – a bright sound colour range of works.

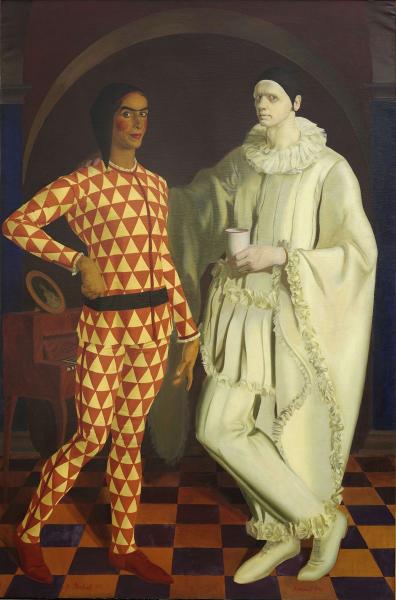

Alexandre Iakovleff’s work is multifaceted, with his desire for monumentality expressed in paintings that trace features of the ‘big style’. Iakovleff’s works are so diverse that the study of his art is a very fascinating process. His early work is connected with the traditions of the Renaissance, then the works are filled with symbolic sounding, which is especially evident in his portraits ‘The Violinist’ and ‘Harlequin and Pierrot’. His drawings are mastery and precision, virtuosity, which in every stroke of a pencil reveals the hand of an outstanding artist.

In the early 1910-ies Shukhaev and Iakovleff performed in the ‘House of Intermedia’ in St. Petersburg in the pantomime A. Schnitzler’s ‘Columbine’s Scarf. Iakovleff – as Harlequin, Shukhaev – as Pierrot. Their double self-portrait – a kind of memory of the passion for the theatre. The painting was not exhibited for many years, as it was not finished. In 1962 Shukhaev finished some details. In the same year, it was exhibited at his personal exhibition at the Academy of Arts in Leningrad. Russian Museum. From Icon to Modernity. St. Petersburg. 2015.

The artists are depicted in the costumes of Harlequin (Yakovlev) and Pierrot (Shukhaev), the heroes of A. Schnitzler’s pantomime Columbine’s Scarf, staged in 1911 by V. E. Meyerhold at the House of Intermedia theatre in St. Petersburg. Having once accidentally got to this performance, the artists became regular spectators, got acquainted with the actors, and the director and one day were invited to perform the main roles. The idea to paint a joint self-portrait, depicting themselves as the heroes of the comedy, came in Italy, where Iakovleff and Shukhaev were after graduating from the Academy. The painting, executed by the two masters, is so integral in the manner of writing that it is perceived as a work created by one hand. It clearly expresses the creative credo of the authors.

‘Violinist’ – a programme work for Iakovleff, created in Italy. He posed for the painting as a seriously ill musician. Having carefully conveyed his individual features, the artist at the same time, as he himself wrote, dressed ‘him up in a completely invented costume, which might have suited (as well as he himself) to Gozzi’s fairy tales’. The violinist stands against a backdrop of architecture: not a ‘palace, not a marionette theatre. In the loggia, there are some figures of people or marionettes’.

We know that the portrait depicts a professional musician, seriously ill with progressive paralysis, ‘very interesting in appearance with an old face, despite his 37 years’. The artist conveyed with great care the individual features of his model and at the same time transformed the nature.

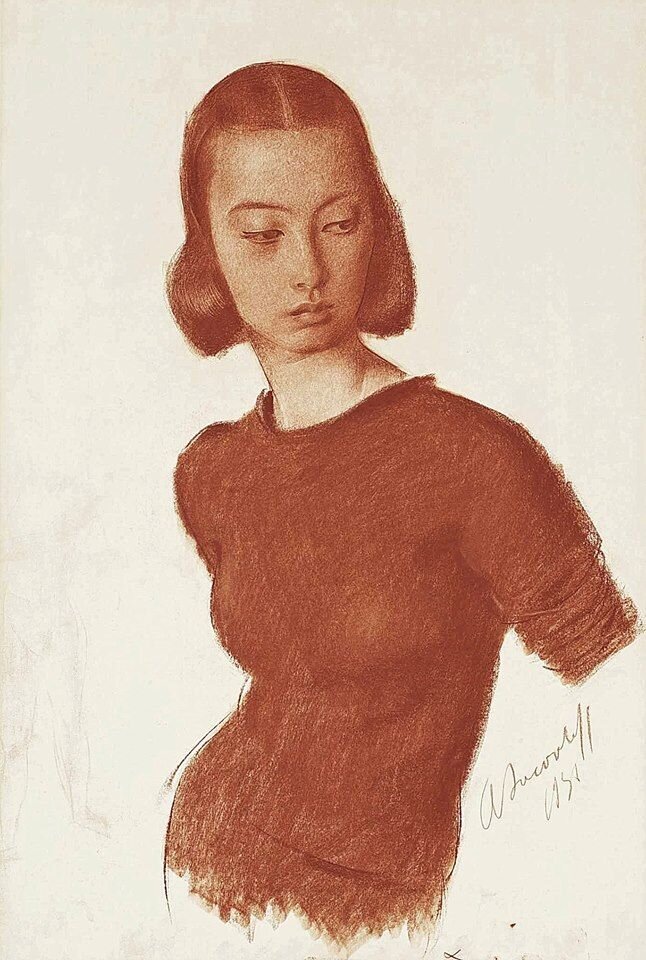

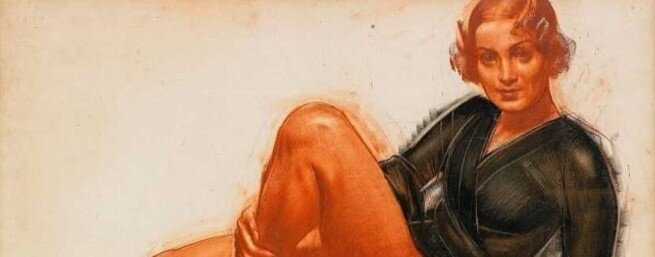

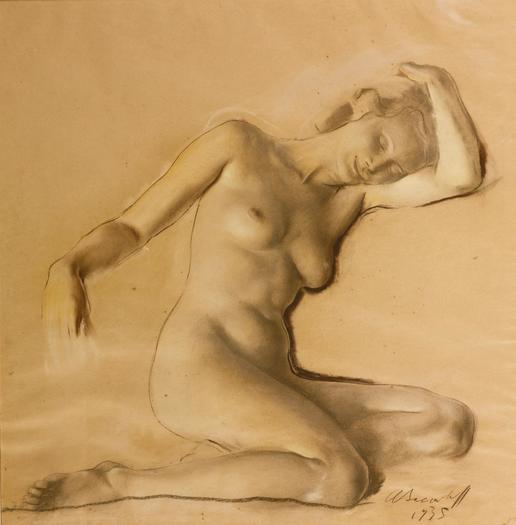

The discovery of Iakovleff and his friends, students of the school of Kardovsky, was sangina, an artistic material which they mastered to perfection. Brilliant moulding of the form was completed by subtle work on light and shadow gradations. Portraits and nudes were especially expressive in this technique. Iakovleff uses the warm tonality of sanguine in all the variety of its nuances.

Sanguine

Sanguine (French: sanguine from Latin sanguis ‘blood’) is a drawing material in the form of a thick, unsharpened pencil or bar of red colour, which consists of a mixture of white clay, iron oxide pigments and vegetable glue. The colour of ‘red chalk’ varies from deep brown to terracotta. Sanguine drawings are lightfast, pleasing to the eye and inexpensive in terms of material cost. Chalk crumbles off the paper, so artists cover the work with varnish or hide it under glass.

The painting technique became popular during the Renaissance because sanguine was easy to spread, created translucent shades and perfectly conveyed the tones of the nude body. Baroque masters appreciated sanguine for its ability to reflect the texture of an object, to create smooth colour transitions or bright ‘dense’ lines. In the heyday of rococo and classicism artists preferred the technique of ‘three pencils’ – a combination of sanguine, black and white chalk. Masters of the XX century did not do without sanguine in drawing sketches of portraits and figurative compositions. The red bar has been an indispensable tool for artists for ten centuries and continues to be so.

You will find sanguine masterpieces among the paintings of Leonardo da Vinci ‘The Last Supper. The Apostle James’ 1495 and “Madonna with a Spindle” 1501. The master with laconic strokes and light touches of chalk creates subtly emotional, spiritualised images. Raphael Santi left his descendants the richest collection of sketches and sketches of famous frescoes. ‘Psyche offers Venus water Styx’, and ‘The Wedding of Alexander and Roxana’ 1517, demonstrate the mastery of the use of sanguine in drawing the nude human body. Peter Paul Rubens also didn’t ignore the technique. The portraits of the artist’s son Nicholas Rubens 1621 and 1627 can hardly be called sketches. Rubens combines sanguine and charcoal drawing on paper, adds tiny touches of ink and… the drawings come to life.

The characteristic pictorial motif, the character of the preparatory drawing, the way of building volumes and space, the development of light and shadow effects and the compositional solution correspond to the creative manner of Alexandre Iakovleff.

Ballerinas have repeatedly become heroines of Alexandre Iakovleff’s works. In the 1920s, the artist repeatedly depicted the legend of world ballet and his close friend Anna Pavlova. In the 1930s, Iakovleff worked a lot on private commissions, including sketches of scenery for the ballet ‘Semiramida’ for Ida Rubinstein’s tour of the Grand Opera House in Paris (1934).

The 1935 drawing shows the ballerina and choreographer Nina Vershinina (1910-1995). In the mid-1920s, her parents sent Nina and her younger sister to Paris, where they began studying with Olga Preobrazhenskaya, a ballerina of the Imperial Theatres. In 1929 she made her Paris debut in Ida Rubinstein’s group, and in the 1930s she performed in L.F. Myasin’s ballet to music by Tchaikovsky, The Omen (1933) and B.F. Nijinskaya’s ballets in Monte Carlo. Nina Vershinina then began dancing in modern ballet in Germany, England and later in the USA. She worked as a choreographer for the San Francisco Opera and the Cuban Ballet. In 1957 the Ballet Nina Vershinina was created in Brazil and successfully existed for many years. Subsequently, she opened her own ballet studio, which produced many Brazilian ballerinas.

Alexandre Iakovleff is one of Russia’s most sought-after artists. This was confirmed at Sotheby’s Russian auction. The most expensive lot was Alexandre Iakovleff’s sanguine ‘Harlequin’, which sold for £730,000.

Earlier at Christie’s Russian auction in London, Alexandre Iakovleff’s monumental ‘Dancer in Spanish Costume’ was sold for £1.1m.

Iakovleff’s drawings have always been in demand in the art market, whether they depict kabuki theatre actors or exotic characters from a trip to Africa.

A. Yakovlev’s artworks are kept in numerous museum collections and private collections. His creative experience is unique, his life has always been full of adventures, travelling and bright events.

Malabart Gallery is thrilled to present the incredible works of a truly unique artist Alexandre Iakovleff in their gallery. Among the amazing pieces on display are ‘Peonies in a Vase’ (late 1920s – first half of the 1930s) and ‘The Winepress’ (1937).