In terms of museums, the Museum of Modern Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Whitney Museum, and Guggenheim Museum tend to dominate talk of the New York art scene, but a much smaller institution has come to influence them. Since its founding in 1968, the attic Studio Museum in Harlem has grown in size and ambition, and its reputation has skyrocketed with it.

Focused on artists of African descent, the institution is today considered a touchstone for contemporary black artists and a conveyor belt for aspiring color keepers. In preparation for the opening of a new home designed by David Adjaye – construction is expected to continue in 2022.

With an ambitious artist placement program, visionary directors (most of whom were women), and high-profile curatorial and educational teams, the Studio Museum is now “the nexus for black creative excellence in the 21st century.” said Christine Y. Kim, who worked there early in her career and is now curator of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Climbing the career ladder of a museum, whether it be an artist or an employee, almost guarantees success in the formative years. Call it the Harlem museum effect. For Thelma Golden, current director, the Studio Museum is a key link in several ecosystems – the art world, the wider cultural environment, and the Harlem community.

The Studio Museum has a wide network of people associated with its growth. Now, as a director, she says that she feels like a part of the community and is just full of gratitude for the work that many have done before.

1968–1979: An Artist Community Grows

During the years when it was founded by activists, philanthropists, and artists, members of the Studio Museum in Harlem engaged in heated debates about the purpose, the board of trustees, and staff of the new museum; people who attended some of its first performances even protested against them.

Within ten years, his mission became clear: he will become a key link in a network of black artists, many of whom do not exhibit their work in major museums and galleries in the city. Thanks to the support they received early on, these artists are now considered some of the most important of their generation, although recognition is often slow and in some cases long overdue.

Over the course of five decades, the Harlem Museum evolved from a young art space to a key institution with a permanent home. These are milestones in its history.

In 1968, the studio museum opened with a solo exhibition of Tom Lloyd in an 8,700 square foot loft on Fifth Avenue. But not all festivities went according to plan – one visitor broke the sculpture.

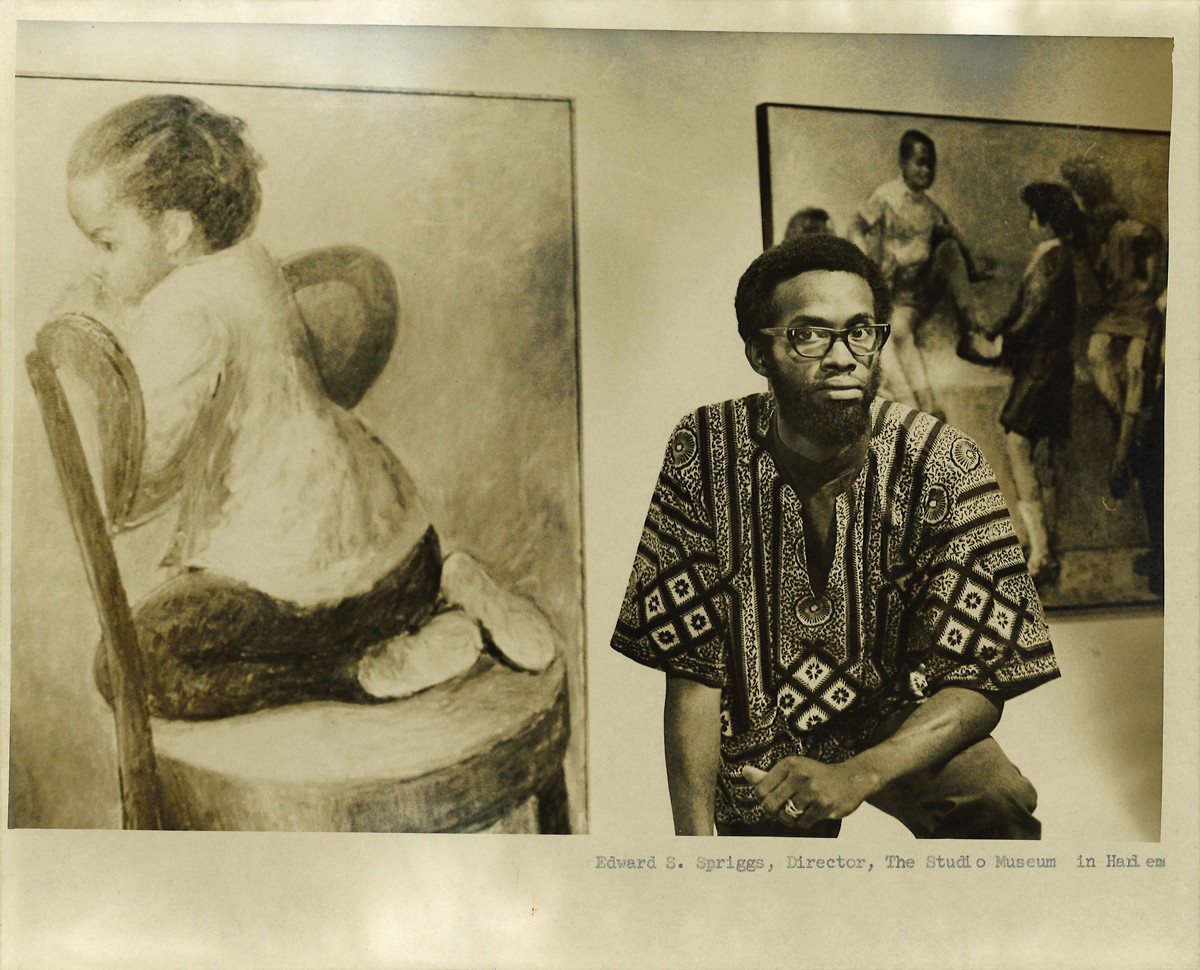

In 1969, Charles Inniss, the museum’s first director, resigned as the local community continued to condemn the Harlem museum for breaking away from what Harlemans wanted. Two months later, Edward S. Spriggs replaced him. The group exhibition, hosted by artist William T. Williams, sparked controversy over the inclusion of Stephen Kelsey, a white artist, and her emphasis on abstraction. Williams was accused of being anti-progressive.

Spriggs left in 1975. His replacement came from outside the arts: Courtney Callender, who worked for the New York City Parks Department and advocated for the preservation of the studio museum in Harlem.

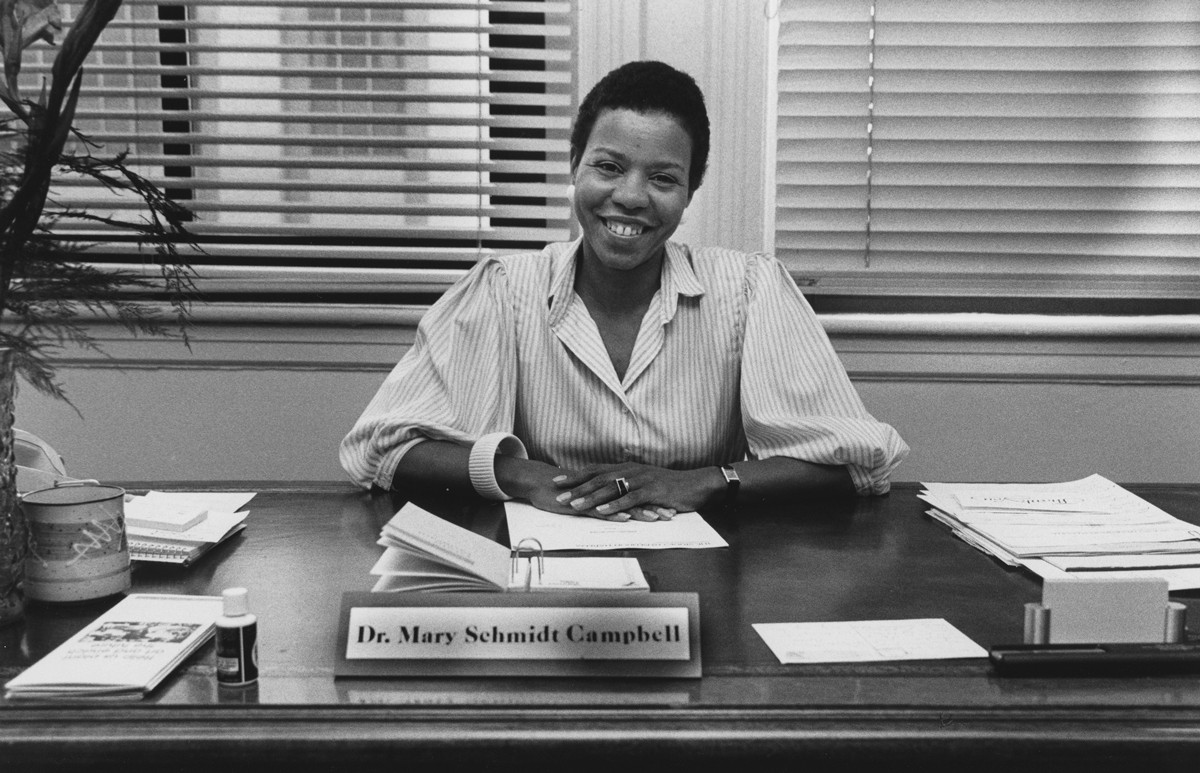

In 1977 Mary Schmidt Campbell became the first female director of the Studio Museum. Since then, the Harlem museum has been run exclusively by women.

Board Games

The mood was tense in the late 1960s when the Studio Museum was created. Harlemites saw the studio museum in Harlem as being attacked by white institutions, as Edward S. Spriggs, the second director of the museum, once said.

Thus began in the museum’s formative years the struggle between the community and the governing body that oversaw the Studio Museum in Harlem, which was initially skewed white – a fact that annoyed Harlem residents who regretted the gentrification and incursion of profit-seeking corporations.

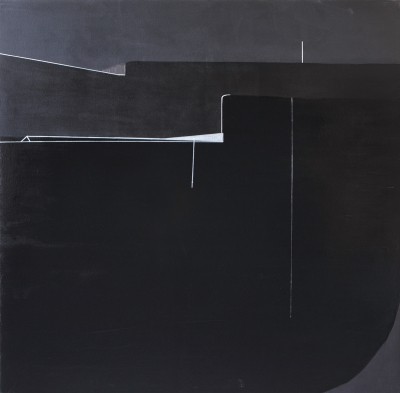

In the early years of the Studio Museum in Harlem, in 1968 and 1969, there was a lack of disagreement over whether it was an organization “on the outskirts” specializing in black art, or “in the center,” showing an interest in the avant-garde emerging in the countryside.

When Spriggs became director, he redefined the museum to work with Harlem in mind. He reorganized the board so that it truly was a “black art museum,” as he put it.

Artists-in-Residence

When William T. Williams began his career as an artist in the late 1960s, he knew several black artists who were represented by New York’s leading galleries. Since most galleries are largely whitelisted, Williams felt he and his colleagues were unlikely to show their art in the vaunted Midtown gallery district.

In an effort to secure support for artists, Williams began work on what is now considered one of the Harlem Museum’s most famous initiatives: its artist residence program. He also created a place where black artists could communicate and learn from each other.

Working alone, Williams presented the museum with a proposal for a program that would include studio space and foster community engagement in Harlem, which Williams called “the capital of black culture – the perfect place to study.”

In the end, the museum accepted Williams’ offer, and the studio space in which the artists were allowed to work gave the museum its name. The Harlem museum’s trustees and curators left the artists on their own, and the program flourished.

Among the graduates of the Kerry Residence, there are James Marshall, David Hammons, Julie Meretu, Kehinde Vili, and Njideka Akuniili Crosby. Among the graduates of the Kerry Residence, there are James Marshall, David Hammons, Julie Meretu, Kehinde Vili, and Njideka Akuniili Crosby. Museums around the world have accepted similar programs.

Williams is credited with inheriting NXTHVN, an art center in New Haven, Connecticut co-founded by artist Titus Kaphar (a graduate of the Artist in Residence program at the Studio Museum in Harlem).

This model, according to Williams, is very important. He thinks it works because there is everything a young artist needs at the stage of development. He says if you have a staff to support you and artists who are willing to invest in your studios, in their ideas, it starts to work.

Mary Schmidt Campbell

Harlem Museum director, 1977–1988; current president of Spelman College, Atlanta

In the 1970s, the Studio Museum in Harlem was a busy crossroads for working artists. They gathered in workshops at their place of residence. They supported each other’s exhibitions, and when the museum began collecting collections, they were assured that their work would be preserved.

The studio museum in Harlem was also one of the rare places in the country to publish regularly catalogs of exhibitions of work, including serious scholarly or critical essays. The creation of the literature that made it to the academy and into the serious study of American art history and the art of the Black Atlantic was one of the museum’s most important contributions.

For Mary Schmidt Campbell, this was the beginning of her career as a curator and art historian, surrounded by the most outstanding and talented artists and in their service.

Since its inception, the Studio Museum in Harlem has prioritized the surrounding community through its exhibitions and public programs.

When Mary Schmidt Campbell arrived in New York in 1977, the whole city was dull, in places destroyed, and Harlem Museum was one of the most physically exhausted. Empty lots, boarded-up buildings, and completely abandoned city estates filled the Harlem landscape.

The studio museum in Harlem was part of a network of non-profit and retail outlets, restaurants, and other small businesses that took root early on to become catalysts for change. They invested in physical rehabilitation of the area along with residents who moved to the city in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

Much of Harlem Museums’ revival has come from permanent residents who planted trees, repaired sidewalks, and invested in capital. They, along with small businesses, cultural groups, and other non-profit organizations – Harlem Dance Theater, Harlem School of the Arts, Apollo, Harlem Stage, and others – have been community allies who have forged connections with local communities and businesses rebuild.

The studio museum in Harlem has also been a place of incubation for talent.

Thelma Golden came from Smith College 30 years ago when I was about to become New York City’s Commissioner for Cultural Affairs. Kelly Jones, MacArthur Research Fellow, worked with me on the Harlem Renaissance exhibition catalog.

They are both renowned leaders in the art community, as are MacArthur collaborator Dawood Bey, a frequent exhibitor, or MacArthur Kerry collaborator James Marshall, a former painter at the Residence Museum of the Studio.

Deborah Willis, photographer, photography historian, and curator, is another MacArthur Fellow who has often filled the walls of the Studio Museum with her expertise.

This catalog of famous people who have worked in the museum does not include artists who were ignored by the art world until the Studio Museum presented a retrospective of their work, including Faith Ringgold and Roy DeCarawa.

1980–1999: Building a Collection

With the Studio Museum in Harlem building a community and auditorium, it was time to take a big step – the 8,700-square-foot loft could no longer meet the needs of the rapidly growing institution. The Harlem museum now had several floors for exhibitions, as well as more storage space for what would later become a growing collection.

By the early 90s, when the museum was run by Kinshasha Holman Conville, the studio museum was referring to what he called a decade of collecting. At that time, almost all of the works that entered the Harlem museum were gifts from artists and collectors. In 2001, the museum formed a commission for the acquisition.

The galleries at the Studio Museum in Harlem came to life – literally – in the 90s thanks to Patricia Cruz, who was then Deputy Director of Programs.

The Long Decade

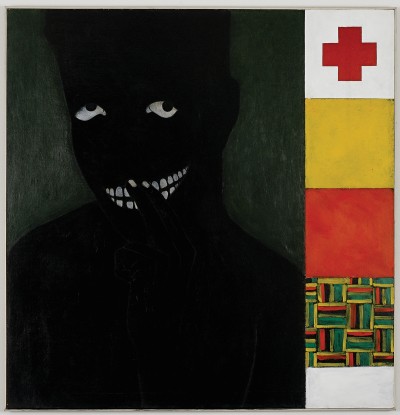

Organizing exhibitions around identity has become the norm these days, but when the Studio Museum organized the Show of the Decade in collaboration with two institutions in downtown New York – the New Museum and the now defunct Museum of Contemporary Latin American Art – it was almost unheard of.

The theme of this show was how artists viewed gender, race, and sexuality in the 1980s, and the range of approaches it presented was vast and varied.

One of the most epic exhibitions in the history of the Studio Museum, it was also rare in this institution, which did not show exclusively artists of African descent – the works of Hans Haake, Amalia Mesa-Baines, Hock EI Wee Edgar Heap of Birds, and others hung in galleries, as well as the work of artists who have previously shown there, among them Melvin Edwards and Faith Ringgold.

2000–2020: A New Generation of Curators Emerges

Over the past two decades, the Studio Museum in Harlem has served as a source of new curators and color educators for major institutions who have hired them to fill leadership positions. When Lowry Stokes Sims was at the Metropolitan Museum in the 70s, 80s, and 90s, she was one of the few outstanding black curators in the United States.

When she became director of the Studio Museum in 2000, she made it a priority to hire people of color for positions they might not otherwise have achieved in a museum-like the Met. By the time Sims became director, the artist placement program had lost its relevance – participants worked in the museum’s offices, and they were even asked to come and go.

Having decided to revive it, she moved into a residence on the fourth floor of the building, is a former law office, and began to allow artists to use their studios around the clock, seven days a week. The Studio Museum in Harlem has had a purchasing committee since 2001, whose influential purchases have helped shape the practice of New York collectors.

Fascinating Freestyle

Thelma Golden and Christina Y. Kim organized Freestyle. The exhibition was the first of the already known “F” exhibitions of the Harlem Museum, a series of thematic exhibitions, the other four were called Frequency, Stream, Fantasy, and Before. And this one showed a certain sensitivity like Post-Black, whose propagandists fought against the Black Artist label, creating art that was not always associated with race.