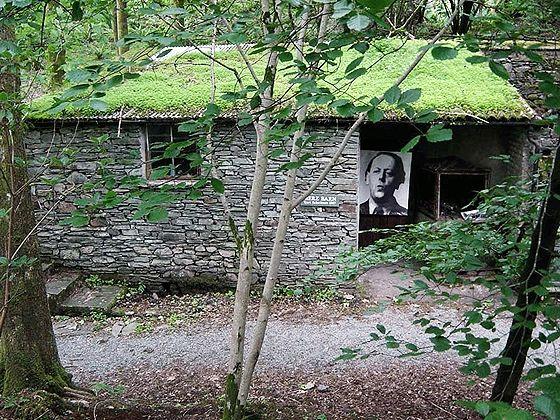

The grey, low slung barn would be easy to pass by during a stroll through the bucolic forests of the Lake District in England. Its stone walls are covered in moss, weeds push and prosper through its lattice roof. But this humble place holds a remarkable history; for it is here that the German artist Kurt Schwitters spent the final months of his life, creating his final masterpiece within its four walls—“my life’s work,” he said.

Now the barn will close to the public, with public funding no longer available. It will likely be sold to a commercial developer as soon as November 2022.

Schwitters was the pioneer of the Absurdist Merz movement, a form of Dadaism and a prototype for Pop art. His work is a stated inspiration for Ed Ruscha, Robert Rauschenberg and, latterly, Damien Hirst, who has spoken of the impact of visiting the barn while a student at Goldsmiths, University of London.

But despite his importance in the annals of contemporary art history, Schwitters spent the final years of his life in the remote seclusion of Ambleside in the Lake District. He first discovered the barn, later known as the Merzbarn, on the Cylinders Farm estate next to the Cumbrian village of Elterwater, in March 1947. The German artist used it as a studio in the months before his death at age 60 in 1948. The barn was owned by Harry Pierce, a local artist whose portrait Schwitters had been commissioned to paint.

Schwitters had worked in virtual obscurity during his time in the Lake District, and generated most of his income by painting the portraits of the landed gentry, or by recreating popular scenes of the surrounding landscapes to sell in tourist shops. A drawing by Schwitters of Francis O’Neill, a local businesswoman, hangs today at the Abbot Hall Art Gallery in Kendal, in the Lake District; the artist made the drawing in exchange for a supply of bread. The progressive work that had made him famous in Germany before the war was not fully recognised by the UK’s established art world of the time.

But shortly before his death, and with his health failing, he received word he had been awarded a fellowship from the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The £1,000 award was allocated to allow Schwitters to recreate for the museum some of the Merz work he made in Germany before his exile from the Nazis. Instead, Schwitters used the money to create the Merzbarn in Elterwater.

Despite his failing health, Schwitters turned the interior of the barn into an alternate reality. He created within its walls conceptual, abstract and Absurdist collages, fusing found objects from the surrounding landscape with images of American consumerist life; his friend, the US-based fellow refugee, Käte Steinitz, would send Schwitters letters wrapped in pages from cheap comic books, which he would reappropriate in his art.

Since then, the barn has become a cherished heritage site, a focal point for Cumbria’s long artistic history. It has remained open to the public thanks to support from the Arts Council England and donations from artists including Tacita Dean, Bridget Riley and Antony Gormley.

The Merzbarn has survived as a public space under the custodianship of Ian Hunter, 75, and Celia Larner, 85, who jointly founded the Littoral Arts Trust in order to protect the barn’s civic status. Hunter and Larner took over the stewardship of the barn in 2006 and worked to secure the structure of the building when it began to fail in 2014. They have recently attempted, without success, to create a consortium to keep the barn from closing.

Speaking to The Guardian newspaper, they say they have made “nine substantial applications for Arts Council funding” over the last decade, each of which has been rejected. Arts Council England responded: “The project has received grants from the Arts Council in the past including investment in a feasibility study into the project. Understandably, there is a lot of competition for national lottery funding from the Arts Council and we’re not able to fund all of the projects that apply to us. Ian and Celia have been loyal custodians of the site and we wish them well in securing a future for it.” The barn has been offered for sale in the past after failing to obtain funding.

An entire wall of the Merzbarn, including the work Schwitters made there, was moved to the Hatton Gallery in Newcastle in 1965. In 2011 the barn was reconstructed in the front courtyard of the Royal Academy of Arts in London as part of its exhibition Modern British Sculpture. Schwitters in Britain, the first major exhibition of Schwitters’s late work, was shown at the Tate Britain in 2013.

Schwitters was born in the German city of Hanover in 1887. He studied art at the Dresden Academy alongside Otto Dix. Schwitters asked to join the Berlin Dada movement in late 1918, according to the memoirs of Raoul Hausmann—but his application was rejected, in part due to his early commitment to the rival movement of German Expressionism and Der Sturm.

The artist became a celebrated artist in the Weimar Republic’s art world but the rise of German fascism soon began to press on his life. His work was included in the Entartete Kunst (degenerate art) exhibition organised by the Nazi party in 1933, which toured Germany. By 1937, he realised he was being surveilled by the Gestapo, leading him to take the decision to leave the country and escape the Nazi regime. Later that year, he fled for Norway, before arriving in the UK as a refugee in 1940. Listed as an “enemy alien”, he was initially held in a Scottish internment camp before arriving in England in July 1940, where he was placed in Hutchinson Camp, an internment camp on the Isle of Man. He moved to London in 1941 after gaining his freedom, before settling in Ambleside, Cumbria, in 1945, after visiting the Lake District on holiday. He died three years later of heart failure.