Henry VIII endures in the history books as a ruthless king with a cantankerous temperament. But a less cocksure man emerges in the margins of his own prayer books.

Following a jousting accident in 1536, Henry spent the final decade of his reign in considerable pain and came to perceive the suffering as a punishment from God for his sinfulness. This is one assessment from Micheline White, an associate professor at Carlton College, whose research into the king’s prayer book at Wormsley Library recently appeared in .

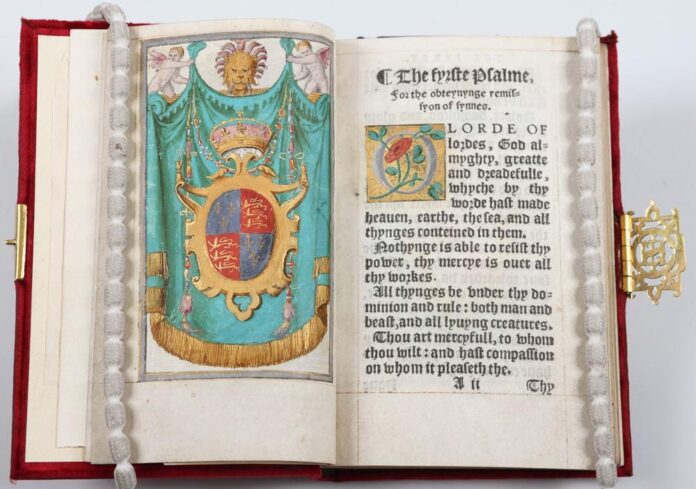

Henry’s prayer book. Photo: courtesy The Trustees of The Wormsley Fund and reproduced with permission from The Wormsley Estate.

The annotations in question largely consist of manicules, a hand with an extended index finger, and trefoils, a grouping of three dots, which the king placed alongside passages he saw as pertinent. “He marked passages that ask God to stop punishing him, to forgive him, and to impart divine wisdom upon him,” White told Artnet News. “These markings reveal that Henry also experienced moments of anxiety and uncertainty about the state of his soul and his position as God’s anointed ruler.”

In one instance, a manicule is placed beside a passage that read: “Take away thy plagues from me, for thy punishment hath made me both feeble and faint.” In another, a trefoil is etched beside the words, “O Lord God forsake me not, although I have done no good in thy sight.”

Manicule in the margins of Henry’s prayer book. Photo: courtesy The Trustees of The Wormsley Fund and reproduced with permission from The Wormsley Estate by Andrew Smart, A. C. Cooper, London.

White’s discovery was somewhat fortuitous: she had just spent a week looking at Henry VIII’s prayer books at the British Library and so immediately recognized those in the Wormsley Library version. A detailed comparison revealed that the manicules’ shape, size, and page placement were the same.

Manicule in the margins of Henry’s prayer book. Photo: courtesy The Trustees of The Wormsley Fund and reproduced with permission from The Wormsley Estate by Andrew Smart, A. C. Cooper, London.

Of perhaps greater importance, White noted, is the provenance of the prayer book. It was a gift from his sixth, and final, wife Katherine Parr, who had translated and produced the book as a piece of military propaganda on the king’s behalf. The king did not mark the prayer book in private, but rather while surrounded by his inner circle, which makes the annotations performative. “I see him acknowledging Parr’s intellectual and political labor as he marked the gift book,” White said.

This moves Parr from the margins to the center of power, a point acknowledged by Henry’s decision to appoint her as Regent when he set off for war with France in 1544. This position of political influence continued after Henry died in 1547, with Parr remaining as an important writer and queen dowager under King Edward.