When one looks at Artnet’s data, especially from our recently published Intelligence Report, there is one statistic that really jumps off the page: only 10 women artists are on the list of 100 most expensive artists worldwide. When digging deeper, our data suggests that male artists are far more expensive than their female equivalents. And it’s not due to a lack of talent or ingenuity.

Paying a historical debt, the contribution of women to the canon has only been recognized in recent years. The first documented female artists emerged during the Renaissance, a time when it was either considered unseemly or completely forbidden for women to be artists. Numerous obstacles stood in a woman’s way to becoming an artist. First and foremost, their training would include the dissection of cadavers and the study of the nude male form, while the apprenticeship system meant that aspiring artists would have to live with an older artist for several years. This made it nearly impossible for Renaissance women to follow this path, as other “expected duties” took precedence. Florentine artist Artemisia Gentileschi (1593 – 1653) was one of the few artists able to practice her passion. Trained by her father, she was the first female artist to be admitted to the prestigious Florence Academy of Fine Arts. Several years later in France, Neoclassical painter Adelaïde Labille-Guiard (1749–1803) became one of the first women artists to be admitted to the distinguished Académie Royale, where she exhibited her works. Soon after, she was appointed : painter to the King’s aunts. Astonishingly, several male painters were so threatened by Adelaïde, that they spread rumors alleging misconduct in order to discredit her. However, she persevered and became a mentor to many other female artists.

Elisabeth Vigee Le Brun, (1782).

One of her contemporaries was the completely self-taught artist Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun. Active during some of the most turbulent times in European history, she was admitted into the French Academy as one of only four female members, thanks to the intervention of Marie Antoinette. Forced to flee Paris during the Revolution, Vigée Le Brun traveled throughout Europe, impressively obtaining commissions in Florence, Naples, Vienna, Saint Petersburg, and Berlin before returning to France after the conflict settled. Only a few years later but on a different continent, American artist Mary Cassatt was born in Philadelphia. Headstrong and independent, she trained as an artist and fled to Europe in order to study Old Master paintings in Spain and France. After befriending Edgar Degas, Cassatt was invited into the Impressionist circle, and by the turn of the century, her reputation was thriving in France. In 1904, she was named a Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur. Soon, American artists in Paris sought her blessing and advice, while wealthy Americans sought her discerning eye and connections. In the same century, Polish-Russian aristocratic artist Tamara de Lempicka took the French art scene by storm. Forced to flee St. Petersburg and the Russian Revolution in 1917, de Lempicka headed for Paris, where she studied painting in the ateliers of Maurice Denis and André Lhote, and quickly found success. By the early 1920s, her works were appearing in major Paris exhibitions, such as the Salon d’Automne and the Salon des Tuileries. Nicknamed “the baroness with the paintbrush,” she is renowned for her Art Deco style which oozed cool chic and elegant sensuality. Not long after, but on the other side of the world, Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama began painting at an early age. Without any formal training, she emigrated to New York to pursue her passion. Now famed for her psychedelic paintings and sculptures, Kusama remains one of the top 10 highest-grossing women artists in the world.

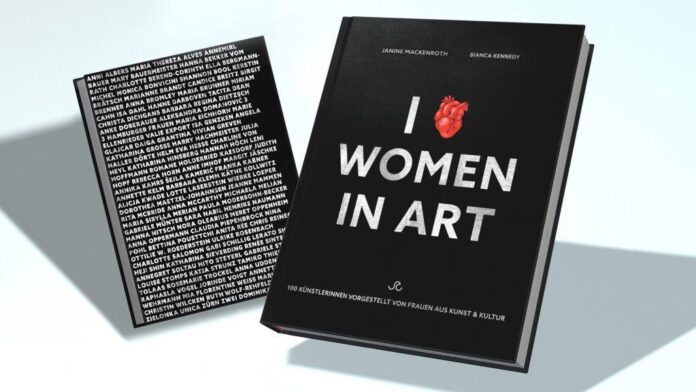

Janine Mackenroth, (2023).

This year, Germany’s new CeU Art Prize endeavors to highlight the extraordinary work of women artists globally. By accentuating the work of women artists, the CeU prize hopes that women artists will be valued not only within the art industry, but also within a political, economic, and social perspective. A team of highly knowledgeable jurors, such as Christie’s executive Dirk Bolla and renowned art advisor Mon Müllerschön were among those selecting the winning artist. With one winning artist and two runners-up, there were numerous submissions for the prestigious prize. The inaugural prize was won by Berlin-based artist Karolin Schwab with Janine Mackenroth a first runner-up.

Visibly touched by the prize, winner Karolin Schwab also revealed to me that she’s currently working “on a public art project, which is a long and slow process. In contrast, I’m also making a painting of the sky every day, which is a very quick process, repeated over a long period of time. I’m curious to see where this kind of archiving of skies will lead me.”

I was lucky enough to ask both artists a few more questions about their processes, inspirations, and life as an artist.

What do you most value in a work of art?

Karolin: Intimacy. The intimate moment between a work of art and yourself. The fact that someone lets you see a part of themselves, resonating with your own world.

Have you always known that you were going to be an artist?

Karolin: Pretty much yes. I proudly told my mother that I would be an artist when I was around 6 years old. She looked at me and asked how I thought that was going to work. I bluntly replied. “I make a painting. Then I sell it. Then I will make another painting.“

Well, it turned out to be a bit more complex than that, but basically, that is where it all began.

What tool or art supply do you enjoy working with the most, and why?

Janine: Nail polish is a love story that started more or less as a hate story. In his famous 2013 interview with , Georg Baselitz wrote. “Women don’t paint very well. That is a fact.” in response to the question of women artists are not that successful. It was the time around my diploma, so I was right before the point of being thrown into an art market, where we still have to listen to such nonsense and face an imbalance of the visibility of contemporary artists based on gender. So I invented a machine that paints for me because as a woman I apparently lack the ability to paint. and I filled it with the most “female” paint you could think of—nail polish. The results were paintings made up of 3,000 bottles of nail polish and more or less a result of coincidence. I love the results, as nail polish is a paint that can be produced with up to 92% bio-sourced materials, which is an important part of my work to use sustainable materials. Also, there is no other paint I have found within my career as an artist that creates these beautiful, smooth effects.

What do you aspire to?

Karolin: Continuing to make work and growing with it. One artwork leads you to the next one, which again leads you to the next one after that. I hope to continue this path for a long time and find myself growing as an artist, making works that mean something to me as well as to the people looking at them.

With regards to the CeU Prize, what do you hope the viewing experience is like for visitors?

Janine: The CeU Prize is the only art prize in Germany dedicated exclusively to honoring women since the Gabriele Münter Prize was awarded for the last time in 2017. Looking at the works of three women artists in Germany I hope the visitors realize the fact, that we are just standing for thousands of other living female artists, who statistically have 50 percent less chance to be shown in a contemporary art show of an art institution in Germany. I am so happy for all of us women artists that this painful gap of an art prize supporting exclusively women in art has now been closed by the Club of European Women Entrepreneurs. The promotion of women in the arts remains essential until their equality in the art world is achieved. So dear visitors, curators, gallerists, auctioneers, buy our work, show it, sell it, auction it!

If you could have dinner with 3 artists, living or dead, who would they be?

Karolin: Phyllida Barlow, Richard Serra, Cy Twombly.