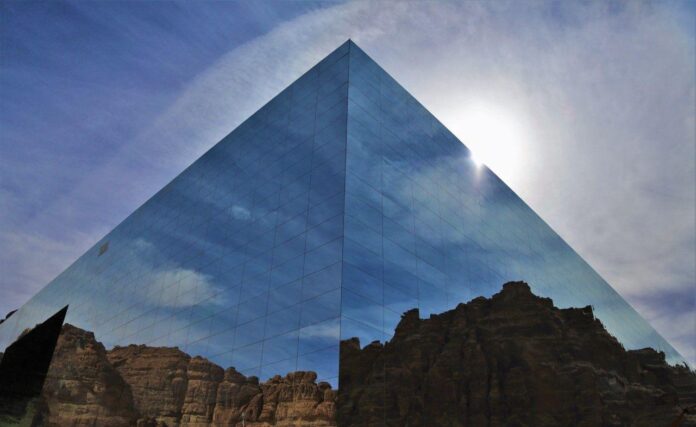

While Saudi Arabia’s mirror-clad desert concert hall Maraya might seem like an unlikely location for an Andy Warhol exhibition, the glamour of the building—fading like a mirage into landscape and reflecting the natural beauty around it—would have certainly transfixed the artist, who saw himself as a mirror of his time and surroundings.

Fame: Andy Warhol in AlUla brings together some of the US Pop artist’s most recognised works to a new audience in the desert city of AlUla, which is slowly being built up as an arts and culture destination.

Curated by The Andy Warhol Museum’s director Patrick Moore in partnership with Arts AlUla, the exhibition dissects Warhol’s fixation with fame; drawn like a moth to a flame to beauty and celebrity, Warhol’s life was also shadowed by tragedy. The show also makes comparisons to contemporary society’s relationship with fame, drawing parallels between Warhol’s experimental film portraits and our all-consuming social media usage.

“I was thinking from the first time I visited Saudi about the indications I saw from young people here that they wanted to be part of the world, to be seen in the world and be part of this larger world culture,” Moore tells The Art Newspaper. “I then thought about Warhol, how this little guy from Pittsburgh, a quite rough industrial city, was striking out to make his fame and fortune in New York City, and there was something emotionally about those two sides that, to me, fit together.”

Moore adds: “If you look at Warhol’s portraits, they were kind of like an Instagram feed of his life and I think that that’s such a pervasive part with young people in the world. I think it really started as an escape, because Pittsburgh, was so brutal in the 1920s, into the 1950s, that fame represented this idea of a fantasy, of a different way of life, of being able to hang out with people who were part of the bigger world he wanted to be a part of.”

Though small, the exhibition traces Warhol’s career, featuring famous pieces like the colourful paintings and silkscreen prints of celebrities such as Judy Garland, Dolly Parton, Marlon Brando and Elizabeth Taylor, as well as rarely seen archival photographs and ephemera.

The show begins with several of Warhol’s screen tests: filmed portraits of hundreds of visitors to his studio The Factory, shot between 1964 and 1966. The three-minute videos show both famous and anonymous visitors staring at the camera, some doing nothing, others smiling or drinking a Coke, like the US musician Lou Reed. The videos have been slowed down slightly for the Fame exhibit, to accentuate the effect: perfect, beautiful visages in dramatic lighting, either showing vulnerability or a well-made mask.

“So many people don’t realise what a serious filmmaker Warhol was,” Moore says. “If you were in New York in that era, and you were kind of a cool person, you’d end up at The Factory. [The screen tests] were almost a kind of guestbook […] they really capture American society in the 1960s.”

The second section looks at many of the well-known paintings and print portraits he created of celebrities like Jackie Kennedy and Princess Caroline of Monaco, many of whom had tragic endings and backstories. The works are almost an attempt to humanise these figures of wealth and beauty, as Warhol would gravitate to those with difficult and relatable lives behind the Hollywood smiles, possibly as a comment on fame’s fleeting nature, stemming from his own insecurities.

His own 1986 self-portraits sit in this room, his face shrouded under camouflage print, behind large sunglasses or focused on his wild, silver “fright wig”.

“He’s transformed himself into the spectre of a figure where there’s always a kind of shield; this kind of extraordinary figure where he really almost doesn’t look like a human being anymore,” Moore says. “I think that Warhol was drawn to artifice and wasn’t really interested in natural beauty, but people who had created a persona for themselves around it. It was a way for him to sit at the cool kids table too.”

The exhibition also includes Warhol’s ground-breaking work Silver Clouds, a sensorial, immersive installation that was a novelty at the time, which was part of what made it so popular. The helium-filled, metallic-plastic shapes were made in collaboration with the engineer Billy Kluver. The installation acts as a playful end to the show, highlighting Warhol’s innovative streak and experimental nature.

The once groundbreaking installation will resonant with local audiences, Moore says. “Being able to show [Silver Clouds] in a place where Warhol and even contemporary art have not been seen so frequently, makes this inherently different than doing a show in London, New York or Paris,” he says. “You just feel like this is a truly new context in which to see the work.”

• Fame: Andy Warhol in AlUla, Maraya, AlUla, Saudi Arabia, until 16 May