On June 7, for the opening of Juan Pablo Echeverri’s debut New York solo show, the skies were an acrid brimstone swirl of toxic ochre, and the streets were illuminated with a sickly, eerie yellow glow. Due to smoke drift from the Canadian wildfires, New York officially had the worst air pollution of any city in the world. One of Echeverri’s signatures, in art and life, was dark humor. He surely would have appreciated this fabulous backdrop of dystopian rapture.

The Colombian multimedia artist Juan Pablo Echeverri had died just over a year prior, in June 2022, at the age of 43. The joint “Identidad Perdida” exhibitions paying tribute to his extraordinary creative output run until July 29 at Between Bridges in Berlin and at James Fuentes in the Lower East Side. The founders of both galleries were on hand at the New York party.

A detail from . Courtesy of the artist’s estate.

Wolfgang Tillmans, who co-curated the exhibitions with the artist’s estate, was all smiles, doling out pizza out on the sidewalk—the artist sporadically assisted the German photographer for a decade, helping him install exhibitions around the globe (when off-duty, Echeverri piggybacked his own practice in the far-flung locales). “Juan Pablo had real star quality to him,” Fuentes said. “He was an extremely compelling presence and infectious. He was also in Wolfgang’s band [Fragile]. He was a man of many talents. There was something quite a bit extra about Juan Pablo.”

He continued, “I can think of many instances in my career where I’ve been overly analytical about shows. The moment that I found out that he had passed, there was this overwhelming regret for not having dug deeper into his practice while he was alive.”

An installation view of Juan Pablo Echeverri’s “Identidad Perdida.” Courtesy of Between Bridges.

“He Was Very Aware of What He Was Doing”

“Identidad Perdida” translates to ‘Lost Identity,’ and Echeverri contained multitudes. The foundation of his practice was photographic self-portraiture, often intertwined with roleplaying and a flagrant queer sensibility.

On the walls at Fuentes were 2017 diptychs depicting Echeverri next to Mexican street clowns who as part of their trade steadfastly develop distinct-as-fingerprint looks. Echeverri commissioned them to outfit him in their attire. The costumes are vivid, but the expressions beneath the greasepaint are inscrutable. Elsewhere, an old-fashioned barbershop sign displays various outdated pompadours and butt cuts on offer—each style using Echeverri as the model.

In Echeverri’s skin is airbrushed to resemble exposed musculature. His face remains plaintive, but the haircuts veer from an unruly caveman shag to a severe fuchsia bowl cut to a mohawk. These aren’t kooky wigs. The series was shot in a single day, and the nine drastic cuts and chemical dyes (and increasingly red eyes) add a subtextual endurance test to the 2003 series.

Juan Pablo Echeverri, (2003). Courtesy of James Fuentes.

This element of performance informs all of Echeverri’s art. An accomplished musician, he was as prodigious with video as he was with photography. His series “Around the World in 80 Gays” features the artist staging guerrilla costumed music videos in front of various worldwide tourist attractions like the Louvre. These clips prefigure TikTok tropes by decades. Gems like 2009’s where a gay beach proliferated with archetypes—all played by Echeverri, of course—who vamp to his Spanish version of Madonna’s “Holiday,” are screened in the lower level of James Fuentes.

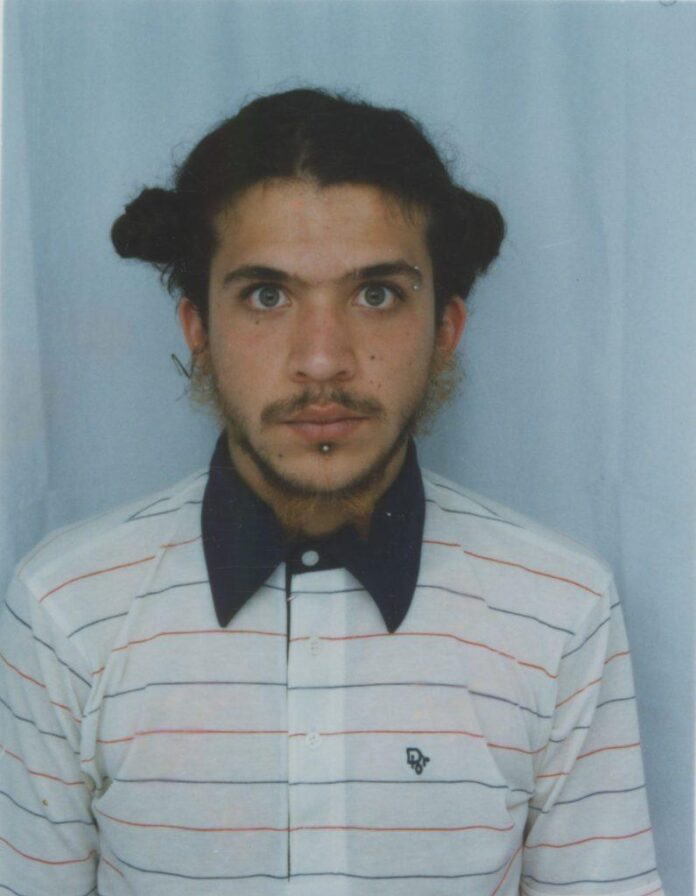

But the backbone of the show, and of Echeverri’s entire practice, is a portion of which is on display. He contributed to it for 22 years by taking a daily passport photo of himself, amassing over 8,000 images. “Every photo—he could tell you exactly what was happening that day,” said the architect Federico Martelli, a friend of Echeverri who also designed the shows’ scenography. “In some, you can tell he’d been crying all day, and it’s probably because he wanted to make sure that when he looked at the photo later on, he could tell he was super destroyed from a breakup.”

is more than just a timeline of Echeverri’s life. It was a study of identity, individuality, stereotypes, and universality. Within its proliferating grid, Echeverri created a universe. Sometimes within the larger project, he would embark on mini-projects, such as using a swath of new photos to recreate outfits from a decade prior, before snapping back to an intimate diary format. was a living, undulating leviathan of shifting rules and presentations. It also served as a test kitchen for his other series.

A detail from . Courtesy of the artist’s estate.

The current exhibitions in Berlin and New York are a compelling introduction to Echeverri, but they only hint at the expansive body of work he left behind. He exhibited for twenty years, navigated group shows and art fairs, and partook in international residencies. He lived and breathed art, but still flew just under the radar. It doesn’t always pay to be ahead of the curve, and his strengths also held him back. For many, humor and fine art don’t mix, and his goofball queer pop sheen belied the rigor and complexity in his methods and the wry social commentary that percolates beneath the surface.

The interior designer Esteban Arboleda befriended Echeverri in their native Bogota 20 years ago and became an early collector. In one of the last pieces Arboleda acquired, Echeverri’s face is completely out-of-focus, his entire body a blur. The work, produced during the artist’s final years, seems a clever play on the slippery nature of identity—but Arboleda asserts that there is much more than meets the eye in this series. “The horrible story of missing persons and assassinations is part of the cultural history of Colombia,” he explains. “Another Colombian artist of his time, Carlos Motta, did a lot more serious and earnest work about queerness and political violence. Juan Pablo’s framework for everything was humor.”

Clearly, it takes serious dedication to make work that seems so effortless and unserious. “’Oh, look at him he’s dressed as different lesbians!’” Arboleda says. “’Isn’t that easy and fun?’ Well, it’s impossible [to create] a mosaic of 36 different characters built with such specificity. I mean, eat your heart out Cindy Sherman and Mariko Mori.”

Images from Echeverri’s PRES.O.S. (2017) series. Courtesy of James Fuentes.

Not every piece has these kinds of direct political undertones, but Arboleda’s husband, the editor-in-chief of David Haskell, sees more underneath the candy-coated exterior. “It is about pain, longing, poverty, and a sense of dislocation in a globalized world,” Haskell explains. “Juan Pablo had a chip on his shoulder that he never got the respect that he’s getting now. It kills me that this is the year that he has a show in New York City and he has people talking about the profound aspect of his work. His work was so poppy, and so viscerally in touch with commercial iconography, and it was so funny—but it’s not like you needed to dig hard to find [its serious side]. If you talked to him about it, he was very aware of what he was doing. He was not a ditzy person. He found ditziness very funny as one of his modes of operating. But I think that people misunderstood the kind of tradition he was working in.”

“Juan Pablo Was Always Juan Pablo“

Juan Pablo’s sister Marcela Echeverri is four years older and bears a striking resemblance to him. “We were extremely close,” she says, “almost like twins in many respects.” Marcela became an anthropologist and history professor. When she was on a research trip to Peru, she remembers, teenage Juan Pablo coopted her darkroom equipment.

“My mother the other day said Juan Pablo never ‘came out’ because he never changed,” she said. “That the idea of coming out, it’s like they were one thing and then they revealed themselves or something. Juan Pablo was always Juan Pablo. He was a very lucky son of parents who were very open-minded, very loving. My house was, in many ways, like a queer community in Bogota. It was a place where there were no real judgements—much the opposite.”

Echeverri in his home. Courtesy of the artist’s estate.

With his long hair and eye shadow, Juan Pablo Echeverri stood out to Santiago Monge when he was signing up for the arts program at Bogota’s Javeriana University in 1997. Monge was a few years older and switching his concentration from architecture to art. “We spent those first six months becoming friends,” Monge says, recalling that he was impressed with Echeverri’s technical expertise in photography, so the two started working on projects together.

“He was living with his parents and brother,” Monge remembers. “His personality was flamboyant, and he was part of the music scene. He knew about the Beatles because of his parents and Guns N’ Roses. He also played guitar and had played with bands before. I was more gay—my idols were Madonna and Frida Kahlo. We linked our two worlds. By the end of 1997 we were a couple.”

Echeverri amassed friends easily. Most of them recall his exact outfit in their first encounter. “He was wearing a Scottish kilt and a choker with a Hello Kitty on it,” says Paola Rico, who took photo and video classes with him. “His way of talking was very particular, like a different sort of language. His eyes were captivating. He could look at you and ask for anything.”

Rico was an out lesbian who played guitar in an all-girl punk band. “People would boo or scream at us when we walked by this section at the university,” Rico says. “We took a lot of public transportation. Some bus drivers would refuse to let him on dressed like that.”

It’s startling how swiftly Echeverri zeroed in on his self as the medium, finding his voice and direction almost at the onset. Rico describes this as a natural segue: The spotlight had always been on him, and he was simply harnessing it.

Echeverri with Santiago Monge, Sofia Reyes, and Paola Rico. Courtesy of the estate of Juan Pablo Echeverri.

“Juan Paolo had unique style,” Rico says, “the way that he dressed and even wore makeup. He turned heads in a conservative, Catholic country like Colombia. Also, Juan Pablo was very intuitive: ‘Okay, here’s a camera; I will turn it on myself because there’s something about me.’” He was also already dressing as a completely different person daily. “But it was about fashion,” she insists. “It was about his expression.”

Echeverri and Monge moved to an apartment where they cohabitated for 13 years. “He is the love of my life for sure,” Monge says. “We grew up as people, as artists, as gay men. We did a lot of things by our instincts, living together and being outspoken and gay with no taboos about our families.” Their place became an epicenter for their burgeoning art school crowd, even post-graduation. “Our house became like Warhol’s factory,” Monge said. “We had a lot of parties. Juan Pablo always wanted to be surrounded by people.”

The apartment was also a showcase for Echeverri’s collections. Many visitors remember a focal point being his collection of various international posters for the 1978 cult film wherein Faye Dunaway plays a fashion photographer with prophetic visions. “He had collections of everything,” Arboleda said, “from Superman dolls to naked Ken dolls trapped in cages hanging in the bathroom to underwear of every color. He was obsessive. He would do everything in this repetitive serial way—including his friendships which were kind of obsessive and crazy.” In many ways, Echeverri’s art became the act of releasing vast editions of himself to collect.

Images from Echeverri’s (2011). Courtesy of the estate of Juan Pablo Echeverri.

“The Beauty of Others Being Others”

Fotojapon is a Colombian camera store chain that was once ubiquitous in Bogota. Starting in 1995, Echeverri would occasionally visit its passport photobooth in order to get an image to accompany his diary. By 2000, this became a sacred daily routine. For the first years, part of the blueprint for his daily self-portrait project was actually having to visit a photobooth.

“It was fun to go to Fotojapon for the first five years or so,” Monge said. “But it became painful to wake up and have to go or find one open on holidays. Juan Pablo kept doing it. He always said, you don’t believe this is important and it is and you don’t take it seriously.” Eventually, Echeverri charmed and impressed a higher-up at the company and was gifted a booth which was installed in his apartment. Later still, Echeverri transitioned to using a digital camera. Monge estimates that the written diaries stopped around 2012. The estate has about 100 of these. ( has an unreleased parallel series. After Echeverri’s solo portrait, whomever he was hanging out with would pile into the booth for a group shot. Sometimes it would reach clown car proportions.)

A detail from . Courtesy of the artist’s estate.

For Echeverri, the process of research never ceased. “When he went to a party, he was always looking at people’s clothing,” Monge says, “because some jacket or some pants might work on a photograph of him or some song to make videos. That was sometimes troublesome in our relationship and other relationships he had, because he was always thinking of taking pictures. We thought Juan Pablo was in this parallel world not living in the moment as intensely and passionate as I was. He was always thinking about his work.”

Echeverri with Sofia Reyes. Courtesy of the estate of Juan Pablo Echeverri.

Echeverri met the artist Sofia Reyes at university. She would become a lifelong confidante and collaborator, helping produce and actualize his series throughout the years. They were in daily contact no matter their distance, and in her he found the perfect counterbalance.

Observation was the key component to how Echeverri would shape his characters, Reyes explained. “You saw people on the street and you see how they move and how they are dressed, and you start to think about those people and how they present themselves,” she said. “It’s all about how to connect with people, about observing the beauty of others being others—the joy of people being themselves. And also, the differences: the girly girl sitting next to a heavy metal guy.”

Juan Pablo Echeverri, (2012). Courtesy of the artist’s estate.

She relates how sourcing the wardrobe could add another layer to the work, one that makes them subtly autobiographical. The act of borrowing became art. “He would always work with the network of relationships around him,” Reyes said. “That part was fundamental. People would recognize those objects in his pictures and feel a part of the work. But it was not always his friends. It was also people who he had fought with or had stopped talking to.” Indeed, it was as if he was using that chaotic energy as a component.

Echeverri built a broad body of work, and was a presence on the international art scene. “He traveled a lot,” Monge said, “but he was like, the world is out there and it’s a fantasy world in a way.” He fiercely remained a Bogota resident. “People still think that Latin America is like an alien, extra-historical space,” Marcela said. “Juan Pablo was very stubborn in trying to get people to see how cosmopolitan and modern Latin America is, and how integrated it is to the world.”

Juan Pablo and Marcela Echeveri in New York. Courtesy of the artist’s estate.

“The World Needs to See This”

In 2022, Echeverri was putting the finishing touches on what would be his final series, for which he would embody an armada of his favorite guitarists, reproducing their stage looks and instruments. The images have never been exhibited.

He was also preparing for a July solo exhibition (his first since 2016) at the Museo de Arte e Historia de Guanajuato in Leon, Mexico. Sofia Reyes was working with him on the project, which would offer a fresh glimpse into . “Juan Pablo was a realist and a pessimist in a way,” Reyes said. “He didn’t feel like this was a big door for his future, but he liked showing his work every time he was given an opportunity. He became very excited, and we would also fantasize about going to Mexico to put the exhibition together. [Working on the show] was like a breath of fresh air after the pandemic.”

Working on the show, the project’s evolution became clearer and clearer. “ is a very intimate series and you can see the different phases of it,” Reyes explained. “The first part of the series was all about haircuts and style and clothing. But the last five or so years, you can see it became more emotional and more about the things that were inside of him.”

“After installing Wolfgang’s 2013 exhibition in Lima, the three of us travelled to a tributary of the Amazon near Iquitos,” Martelli explained. “It was all completely flooded so we depended on locals to help us move around in canoes. Juan Pablo befriended one of them who later helped us film .” Courtesy of Federico Martelli.

The curator Ana Castella flew to Bogota to meet with Echeverri. “He showed me his house and I was really impressed,” she said. “Every room that we discovered, I got more excited. When I entered the music room, I was just blown away. I was even texting my boyfriend, ‘This is like meeting Andy Warhol.’ We did a tour of his house for like four hours. Even the laundry was amazing. He was not a hoarder, but a collector. Every type of Garbage Pail Kid T-shirt, wigs, anything in music, and posters.”

She added, “He mentioned he was obsessed with some certain trees in Africa that looked like Muppets. He made you look at the world in a very different way. He was fabulous, but also problematic in a way. He liked conflict. He liked drama. When I met him, he was complaining about back pain and heartache.”

In May, Echeverri went to Lagos, Nigeria to install a Tilmans exhibition. During his stint, he accrued multiple mosquito bites. Weeks later, once back in Colombia, he started to feel unwell, assuming at first that it was covid. He decided to rest the weekend so he would be better for his upcoming Mexico trip. By Sunday he was placed in the ICU at the hospital, and doctors discovered he had malaria. By that Wednesday, he was gone. His sudden passing was devastating to his tight circle of friends.

An installation view of in 2022 at the Museo de Arte e Historia de Guanajuato. Photo: Diego Torres.

The Mexican exhibition was mere weeks away. Echeverri’s daily chronicle of his life would be spread out in an eye-level panorama. It was a new way of seeing his work, an immersive requiem, eloquent and elegiac. Castella remembers finalizing the exhibition. “The show is about the life of an artist every day—and then it stops, and it’s surreal,” she said. “I think this is his grand gesture. The museum and everybody [involved] was like, how do we deal with this? But we pushed forward and it was very emotional.”

For his loved ones, the fact that Echeverri lives on through his art is bittersweet. “He was always struggling,” Monge says. “I’m going to start crying because that’s the thing that makes me most sad on this day: All of this recognition has come after he died. He was recognized here, but everybody saw him as a ‘gay artist,’ as a joke not to be taken seriously, not dealing with Colombia’s big problems—the political stuff. We were living in Bogota in the ‘90s and 2000s, and we were part of that fabric of violence. We invented our own little world because we didn’t want to face that violence that we felt around us.”

An installation view of in 2022 at the Museo de Arte e Historia de Guanajuato. Photo: Diego Torres.

“In terms of the evolution of his work,” Haskell noted, “basically half of his career was before the selfie and half of it was after the selfie. It was about going on an anthropological safari, inhabiting the ‘other’ in some way. He’d do 12 variations of this theme, 12 variations of that theme. The more recent work really felt like expressions of ‘self’ more. I don’t think in the beginning it was about expressing himself. It was about wanting to be Snarf from But then it became more, ‘Where am I in this?’”

“Juan Pablo didn’t want to please anybody,” Castella said. “He didn’t want to please an art market or certain aesthetic trends. But the world needs to see this. I don’t have any doubt that Juan Pablo’s work is MoMA material and should be in great collections. I’m sure that’s going to happen. It might take some time—but the work speaks for itself.”

She continued, “For those people who didn’t meet Juan Pablo—that’s quite a loss. Just spending an afternoon with him was an adventure, like being in a music video.”