Charles Gaines has unveiled his ambitious public art piece on New York’s Governors Island. All it took was eight years, a massive team of fabricators that included amusement-park engineers, and a whole lot of persistence.

The work, part two of his ambitious three-part project “The American Manifest,” offers a piercing critique of American capitalism that the artist hopes illustrates the way that seemingly disparate forces have shaped our nation.

“It shows the history of slavery and Manifest Destiny and colonialism and imperialism as a interlinking narrative,” Gaines told Artnet News at the press preview for the artwork. “In education they’ve been separated, but the U.S. economy was built on slavery. Manifest Destiny legalized the taking of land from other people.”

Perched on the edge of the island beneath Outlook Hill—which offers a great bird’s-eye view of the piece—the monumental kinetic artwork is an overwhelming sensory experience. Viewers can walk through the sculpture along a 110-foot walkway, immersed in the cacophony created by nine rows of steel chains, each in motion and weighing a collective 1,600 pounds.

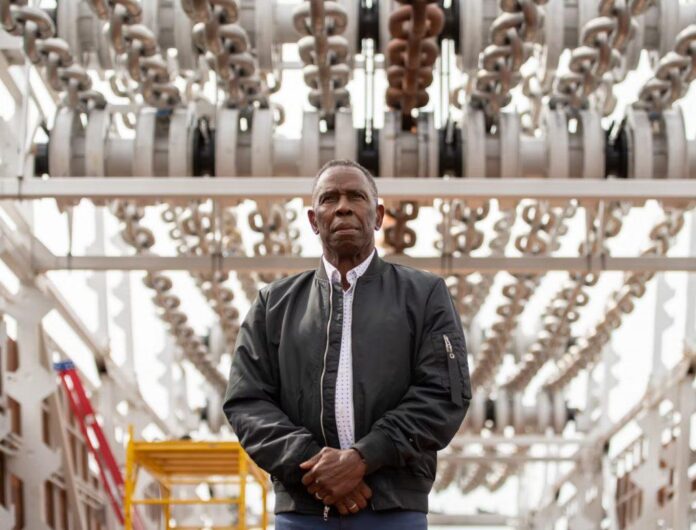

Charles Gaines, in “Charles Gaines: The American Manifest, Moving Chains” on Governors Island. Photo by Timothy Schenck, courtesy of Creative Time.

Stepping inside, you almost feel as though you’re trapped under deck, about to be swept out to sea—which makes sense, as the artist envisioned the kinetic portion of the work as a steel chain river, with eight of the chains matching the pace of the harbor’s currents. The central chain moves much quicker, like a barge steaming along to its destination.

“Standing in the middle of it and hearing the sounds exist in time is pretty emotional,” Gaines said.

Charles Gaines, in “Charles Gaines: The American Manifest, Moving Chains” on Governors Island. Photo by Timothy Schenck, courtesy of Creative Time.

The 78-year-old artist is best known for his grid-based drawings; this is his first public art project. It was originally designed for a Creative Time commission for St. Louis that would have sat beneath the Gateway Arch on the banks of the Mississippi River. When the funding fell through, the unrealized sculpture found itself in the art-world version development hell—but Creative Time never gave up.

“For eight years, they kept the project alive and they kept trying to find a new location and funding for it,” Gaines said.

Charles Gaines, in “Charles Gaines: The American Manifest, Moving Chains” on Governors Island. Photo by Timothy Schenck, courtesy of Creative Time.

In fact, even as the original creative team left the organization, they remained committed to the project. landed on Governors Island thanks in large part to former Creative Time curator Meredith Johnson, now vice president of arts and culture and head curator at Trust for Governors Island.

And the delay allowed the project to expand into a multipart affair, with chapter one taking place over the summer with the Times Square Arts—where another former Creative Time staffer, Jean Cooney, is now running the show. It featured a sculptural display, titled , of a grove of seven upside-down sweetgum trees, as well as the performance .

Charles Gaines, in “Charles Gaines: The American Manifest, Part One” in Times Square. Photo by Michael Hull, courtesy of Creative Time and Times Square Arts.

For part three, will travel to the banks of the Ohio River in Cincinnati—transporting it meant packing sections of the 60-ton work on flatbed trucks and shipping them via barge.

It also took a veritable army to bring Gaines’s vision to life, with architecture by TOLO Architecture, construction by Torsilieri and Sons, woodwork and metalwork by Stronghold Industries, sound engineering by Arup, and engineering by AOA, which specializes in building immersive exhibitions and theme park attractions.

Charles Gaines with his piece in “Charles Gaines: The American Manifest, Moving Chains” on Governors Island. Photo by Timothy Schenck, courtesy of Creative Time.

“The fabricators were very intrigued by the piece, because nothing like this has ever been built before—something that didn’t really have a function hit nevertheless has to perform,” Gaines said.

The sculpture is an abstract one, but the combination of its form and location is meant to evoke a ship, the “hull” made from sustainably harvested Sapele, known as African Mahogany. And the chains recall the bondage of enslaved people, captured for the terrible journey to the New World from Africa.

Charles Gaines, in “Charles Gaines: The American Manifest, Moving Chains” on Governors Island. Photo by Timothy Schenck, courtesy of Creative Time.

Overlooking both the Statue of Liberty, global symbol of freedom, and Lower Manhattan, where slave ships would have arrived from their Transatlantic journey, , represents the contradictions in U.S. history, and the dark taint slavery still leaves on the nation’s legacy.

“I hope it encourages a conversation about these issues,” Gaines said. “In this country, there’s a general belief that a work of art is supposed to be an expression of beauty, that art isn’t intended to contribute to the political or social understanding of society—but the two parts are inextricably linked. Art as an aesthetic experience its purpose.”