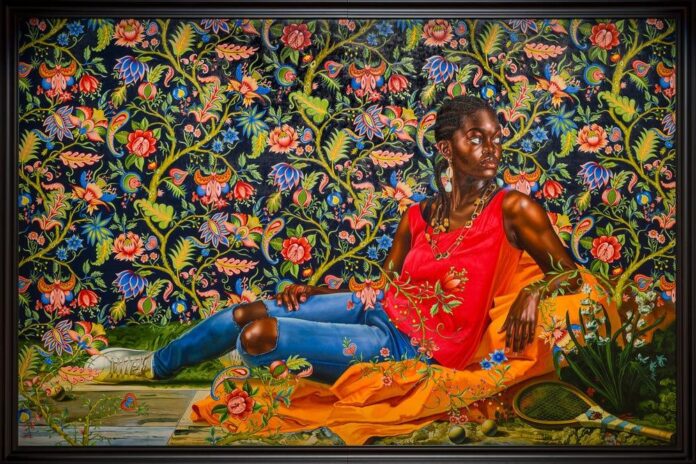

In massive and vibrant works, Kehinde Wiley has again turned to his customary subject matter of young, streetwear-clad Black men and women, here cast in bronze or painted against ornamental and floral backdrops—but this body of work has an undeniably ominous quality. Each piece depicts a fallen figure, drawing on historical representations of death and sacrifice.

“It’s heartbreaking work,” Wiley said during a press tour of his new exhibition at San Francisco’s de Young Museum. He made the 25 paintings and sculptures in “An Archaeology of Silence,” many of which are larger than life, in response to the police killing of George Floyd and the ensuing protests that swept the U.S. in 2020.

The work is a continuation of Wiley’s series “DOWN,” begun in 2008 and inspired by Hans Holbein the Younger’s (1521–22). The new works draw on leftover photos of models who Wiley cast from the streets of New York for the “DOWN” series, as well as new images of staff and friends at his Black Rock Senegal residency program in Dakar.

Much of the art is monumental—paintings the size of billboards and a nearly 18-foot-tall equestrian bronze that is perhaps the largest work ever installed at the museum. But so is the scale of the societal issues to which the works are responding: the specter of racism, the history of brutality inflicted on Black and brown bodies, and the deep sense of loss in the Black community.

An elegiac tribute to victims of racial violence, the exhibition serves as a reminder that for each Black life lost, there is a family in mourning. The commanding presence of the individual paintings and sculptures serves almost as a physical manifestation of grief. And each subject is treated with a reverence typically reserved, throughout art history, for white subjects—fallen heroes or religious figures such as the martyrs and saints, or even Jesus Christ.

Presenting “An Archaeology of Silence” in the Bay Area is something of a homecoming for the Los Angeles-born Wiley, who received his BFA from the San Francisco Art Institute in 1999.

“I was actually the nude model for all of the figure classes for a brief time. It was the highest–paying job on campus, and I wasn’t turning it down,” Wiley said. “But the strange thing was being in class posing for my classmates. It was just a little bit awkward.”

Kehinde Wiley at his exhibition “An Archaeology of Silence” at the de Young Museum in San Francisco. Photo by Gary Sexton, courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Wiley credits his time at the institute with helping hone his skills as a figurative painter—but also with forcing him to realize he would have to adapt his techniques to more accurately depict Black skin tones.

“There’s a tradition of learning how to create shadows and light and molding the body into something that’s beautiful that I learned through painting whiteness,” the artist added. “You fast forward to the present day when I’m working globally and exploring the far ends of Senegalese deep, deep, deep Black skin tones… it becomes this interesting play on light and color that has very little to do with the classical Western notions of playing with light.”

Kehinde Wiley, Photo by Ugo Carmeni, courtesy of the artist and Templon, Paris, Brussels, and New York.

The exhibition debuted last spring as a collateral event for the Venice Biennale at Fondazione Giorgio Cini, before stopping at Paris’s Musée d’Orsay.

Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (FAMSF) director Thomas Campbell saw the show in Venice and, later that same day, spoke with Claudia Schmuckli, the museum’s contemporary art curator, and Ford Foundation president Darren Walker about the urgency of showing the works in the U.S.

By the end of the conversation, Walker had agreed to partner with the FAMSF on the show.

Installation view of “Kehinde Wiley: An Archaeology of Silence” at the de Young Museum in San Francisco. Photo by Gary Sexton, courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

The Ford Foundation provided a $1 million grant for the exhibition, an amount later matched by Google.org.

Ahead of the company’s meeting with Campbell, “we literally rehearsed how to say no,” Justin Steele, Google’s director of giving, admitted at the exhibition’s opening reception. But when he saw the art and learned the story behind it, “I was like ‘damn, you got me!’”

Kehinde Wiley, (2021). Photo by Ugo Carmeni, courtesy of the artist and Templon, Paris, Brussels, and New York, ©️2022 Kehinde Wiley.

Even with that financial support, transporting the show across the Atlantic was no easy task.

“We shipped it all by air freight. There’s a limited number of carriers that can carry such large sculptures,” Campbell told Artnet News, noting that transportation alone cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.

But the museum also had to grapple with the show’s sensitive subject matter. How would these works be received in the demographically diverse Bay Area with its long history civil rights activism, from the founding of the Black Panthers just across the bay in Oakland in 1966 through to the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020?

“For all too many of our visitors, this is lived experience,” Campbell said. “This is very complex and potentially upsetting material, and we are working with the community to support our visitors in this experience, but also to engage with groups that are working on restorative justice.”

Kehinde Wiley at his exhibition “An Archaeology of Silence” with his sculpture of the same name at the de Young Museum in San Francisco. Photo by Gary Sexton, courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

It was these kinds of concerns that prompted the museum to hire its first director of interpretation, Abram Jackson, last year.

In the early stages of planning for the show, the museum considered placing its titular artwork, the giant equestrian sculpture, in its main courtyard. “We decided it probably wouldn’t be appropriate to have a representation of Black death in this public thoroughfare,” Jackson told Artnet News. “And that’s when we realized, ‘wait a minute, this is going to be something we have to be very intentional about.’”

To create the piece, Wiley made a 3-D scan of a 1907 monument to Confederate general James Ewell Brown “J.E.B.” Stuart in Richmond, Virginia. He then created his own version, but with a lifeless Black man lying over the horse’s back. (Wiley also made a more triumphant version with a Black man in a hoodie, now on permanent display at Richmond’s Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.)

Installation view of “Kehinde Wiley: An Archeology of Silence” at the de Young Museum, San Francisco. Photo by Gary Sexton, courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Museums have run into controversy with works confronting racial violence in the past. In 2020, the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland cancelled an exhibition on police brutality by the artist Shaun Leonardo after pressure from local activists.

To avoid a similar outcome, Jackson reached out to organizations in the local community, striking up conversations about the themes of the show, the realities of systemic racism and racial violence, and how the work could be presented in a way that wouldn’t be triggering.

Kehinde Wiley, 2022 (detail). Photo by Ugo Carmeni, via Kehinde Wiley and Templon, Paris, Brussels, and New York.

One of the decisions that came out of those conversations was to create a dedicated “respite room,” where visitors can step away from the exhibition’s powerful images to rest and reflect. The space offers literature on issues of race, and a resource list with information about mental health and advocacy organizations.

Seven groups signed on to be what the museum has called its “interpretation partners,” working closely with the Jackson and the curators to develop the didactic treatment for the exhibition, including the wall text and audio guide.

“There were so many rich contributions from our interpretation partners,” Jackson said. “They shifted our use of state-sanctioned violence to system to systemic violence. They encourage us to say ‘Black people’ instead of ‘the Black body,’ and ‘victims and survivors’ as opposed to just ‘victims.’ And they made the case for incorporating more about Black joy, resilience, and resistance into the texts.”

Kehinde Wiley, (2022). Photo by Ugo Carmeni, courtesy of Kehinde Wiley and Templon, Paris, Brussels, and New York.

That was very much in keeping with the artist’s intent in creating these works. Though the show’s subject matter is rooted in tragedy, Wiley didn’t want it to be about Black pain.

He uses bold colors and monumental scale to turn a dark moment in U.S. into an opportunity to recognize and appreciate “an African American tradition of defiance, of survival, of resilience,” he explained, pointing to elements of plant life in the works as symbols of “growth amid the decay.”

“It’s an insistence upon beauty, upon grace, even in the midst of the worst of what humanity has to throw at you. It’s an insistence upon being able to be visible,” Wiley said. “When it comes to who these people in the work are, there’s a stubborn holding on to life and celebration In the midst of all of this suffering.”

Kehinde Wiley, , 2021. Photo by Ugo Carmeni, courtesy of the artist and Templon, Paris, Brussels, and New York.

In San Francisco, the themes come to the fore in a way they could not in Venice. Amid the lagoon city’s ornate palazzos, it was much easier to focus on Wiley’s art historical reference points than the pressing 21st-century social issues that served as his inspiration.

“So much of what I adore in Venetian painting has to deal with light and the religious and the erotic, the sort of navigating the two twin desires of salvation and penetration,” Wiley said.

Building on this theme, the artist has lit the exhibition like a darkened chapel, with spotlights dramatically illuminating each work.

Kehinde Wiley, (2022). Photo by Ugo Carmeni, via Kehinde Wiley and Templon, Paris, Brussels, and New York.

The scale of Wiley’s production also hearkens back to the Renaissance. While Wiley does the figures, a small army of assistants—working across studios in Brooklyn, Dakar, and Lagos, Nigeria—paint the backdrops for each canvas, replicating the artist’s flat surfaces, devoid of any visible brushstrokes. (The sculptures are manufactured in Beijing.)

“I can fly the world and ask bigger questions and make bigger bronzes and make larger provocations,” Wiley said. “But I think at its best, what the work is doing now is to be able to exercise moments of quiet and intimate conjecture.”