A Paris administrative court last week ordered the Musée d’Orsay to restitute four masterworks by Renoir, Cézanne and Gauguin, which were stolen during the Second World War and sold to the Nazis, to the heirs of the hugely influential French art dealer Ambroise Vollard.

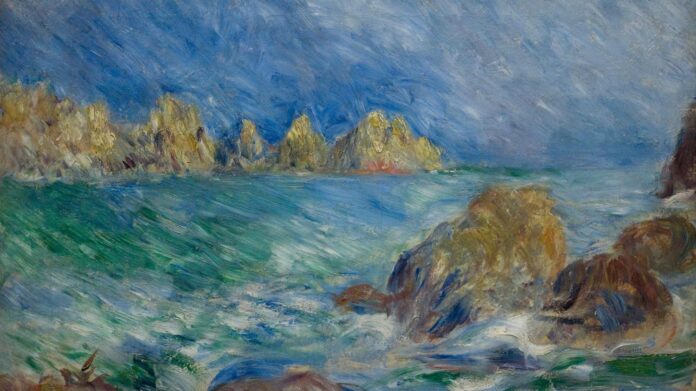

The museum will return two Renoir paintings: an 1883 seascape of Guernsey and a sanguine study (around 1908-1910) for the Judgement of Paris (owned by the Cleveland Museum of Art), as well as Still life with mandolin (1885) by Gauguin and the watercolour Undergrowth (1890-1892) by Cézanne.

The court’s decision was expected. In May 2022, another court had confirmed that these works were the property of Vollard at the time of his sudden death in 1939, before being stolen by the experts in charge of his succession, who then sold them to German museums, dealers or Nazi officers. This judgement was upheld by the High Court last November. The last step has now been taken by the administrative jurisdiction which had to formally endorse the restitution. The French state—under whose purview the Musée D’Orsay falls—has indicated it will not appeal.

On a databank of some 2,000 works recovered in Germany after the war which have failed to be returned to their legitimate owners, the Culture Ministry wrote “to be restituted” on each of the four files. Nevertheless, it took a decade for Ambroise Vollard’s heirs to obtain this victory, in a country where the museums habitually offer stiff resistance to restitutions.

However, the case of Vollard’s inheritance is complex. He was a formidable dealer of Post-Impressionist and Modern art, known for working with 19th- and 20th-century heavyweights such as Picasso, Bonnard, Renoir and Cézanne. He died aged 73 in a road accident, hit in the head by a bronze carried in his car. He left more than 6,000 works to his brothers and sisters, leading to long feuds over how they should be shared. With the complicity of his brother, Lucien Vollard, who was designated as his executor, part of the inheritance was stolen by two experts, Étienne Bignou and Martin Fabiani, who were working closely with the Germans. They were both condemned after the Second World War for illicit profits, but stayed active for decades afterward.

In 2013, Vollard’s heirs requested the restitution of seven works allegedly stolen by the experts. The state refused, arguing that the circumstances of their transactions were not sufficiently clear. Furthermore, Vollard was not Jewish and his properties were not seized under the racial laws enacted by German-occupied France. But the magistrates stated that any work recovered in Germany after the war “has to be restituted to its legitimate owner or beneficiary, even if it had not been looted” by the Nazis.

Vollard’s heirs are still requesting the restitution of three other paintings from his stock: one depicting a bouquet of roses, and another of a group of bathers, both by Renoir, and a head of an old man by Cézanne, which was for a time considered a self-portrait. Although it has been established that the bathers were bought by the Köln Wallraff-Richartz Museum in 1941 from Bignou, the French state says no trace of this sale can be found. In the case of Cézanne’s portrait, which was sold to a head of the SS by Fabiani, the state claims that the expert had before purchased it from a Vollard sister.

One of the heirs’ lawyers, François Honnorat, tells The Art Newspaper: “Although it seems normal for the State to check the history of the works, before restitution”, he “regrets that the process took ten years”, during which two of the heirs died.